Claudy bomb: A priest who got away with murder?

- Published

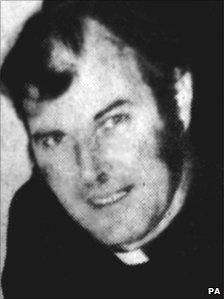

Fr Chesney, who died in 1980, was never questioned by police

Secret files from 1972 show that parish priest James Chesney was, in effect, Father Untouchable.

Extracts from the state documents in the report by the NI Police Ombudsman confirm that even traces of explosives found in his car were not enough to get him arrested.

Intelligence information not only linked him to the Claudy bombing in which nine people died, it also indicated that he was the "quarter master and director of operations of the south Derry Provisional IRA".

So why was he never questioned?

Why was he allowed to move away from Northern Ireland?

And why was he allowed to make trips back across the border without being arrested?

The 26-page report does not fully answer any of those questions. It deals with the how, rather than the why.

Mark Simpson explains the report findings

He was able to do it because of a secret agreement between the Catholic Cardinal William Conway and the then Northern Ireland Secretary Willie Whitelaw.

Nowhere in the report is there any explanation from either man as to why exactly they came to this arrangement. And as both are now dead, we can only speculate as to their motives.

The most generous theory is that they felt that protecting the priest was the lesser of two evils.

During that turbulent period in 1972, many believed that Northern Ireland was on the brink of a sectarian civil war. Almost 500 people were killed that year.

If a priest had been arrested in connection with the Claudy bomb, it could have pushed community relations over the edge.

Loyalist paramilitaries may have used it as an excuse for more attacks on Catholics. The IRA would have retaliated and turmoil would have ensued.

A bad situation could have been made worse.

Flawed investigation

This appears to have been the view of at least one police officer at the time.

Described in the Ombudsman's report as a detective inspector, the un-named officer wrote six months after the bomb: "Before we take on ourselves (sic) to arrest a clergyman for interrogation... we would need to be prepared to face unprecedented pressure."

But, interestingly he adds: "Having regard to what this man (Fr Chesney) has done, I myself would be prepared to meet this challenge head on."

It seems the police hierarchy did not share this view as there is no record of the priest ever being questioned.

This is in spite of the fact that even after being moved by the Catholic Church from County Derry in Northern Ireland to County Donegal in the Irish Republic, police discovered that he "regularly travelled across the border".

Nine people were killed as three bombs exploded in Claudy

For the families of the nine people who died in Claudy, it will be difficult - if not impossible - to see how the protection of Fr Chesney was the right decision.

The role of the police is to investigate crime and not to be influenced by political pressure.

The findings of the Ombudsman will not come as a great surprise. The police themselves admitted it was a flawed investigation in 2002.

What has emerged is simply more detail about the mistakes that were made.

The sudden death of Fr Chesney in 1980 means he is not able to defend himself. The failure to arrest him meant he never got a chance to tell his side of the story.

Although the police had a huge file of intelligence information linking him to terrorism, they did not seem to have much hard evidence.

However, for most people in Claudy, Fr Chesney will be forever remembered as the priest who got away with murder.