US 'has no spare change for NI trade mission'

- Published

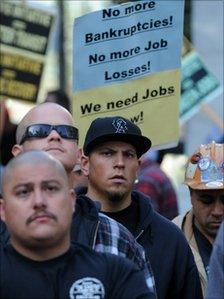

The US unemployment rate is higher than in Northern Ireland

As Northern Ireland's first and deputy first minister arrive in Washington DC for an economic conference organised in partnership with the US Department of State, US-based journalist Niall Stanage looks at the prospects for investment.

Any push for jobs is likely to be popular back home, especially when it carries the imprimatur of Hillary Clinton.

Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness has hinted that additional good news may come in the form of modest job announcements at the conference itself.

Even so, expectations should not be allowed to spiral out of control.

The Stormont ministers will have a very hard battle to attract investment on a truly transformative scale.

The reasons are quite simple.

Northern Ireland has always struggled to make a compelling case to hard-headed business people, being geographically peripheral to the rest of the UK and burdened, for now at least, with a much higher corporate tax rate than the Republic of Ireland.

Sympathy dollars

To try to overcome these disadvantages, its representatives have repeatedly insisted that inward investment might enable a final escape from the legacy of the Troubles.

But the attempt to extract sympathy dollars is made much more difficult by the fact that huge swathes of the US have been hit harder by the Great Recession than has Northern Ireland.

The latest figures released by Northern Ireland's Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment note that the unemployment rate averaged 7% for the three-month period from June to August.

The US unemployment rate is significantly higher, at 9.6%.

In several huge and politically important states it is higher still: 13.1% in Michigan, 12.4% in California and 11.7% in Florida.

If Northern Ireland were a US state, it would be as well or better off in terms of employment than all but nine of the 50 states in the union.

With the outlook so gloomy at home, American corporations are generally more focused on retrenchment than expansion.

And the US public is in such an unforgiving mood that there is limited space for manoeuvre for even the best-intentioned American politician.

Fine words about peace and prosperity are all very well, but anything that could be seen as an encouragement of large-scale outsourcing would carry serious political risks.

Catalogue of disappointment

There is also the rather chequered history of American promises to Northern Ireland to consider.

The catalogue of disappointment does not begin and end with the infamous DeLorean Motor Company farrago three decades ago.

In April 2008, much hullabaloo attended the announcement that New York City's public pension funds would invest up to $150m in the Emerald Infrastructure Development Fund. This private fund was, in turn, supposed to invest in projects in Northern Ireland.

No investment was ever made. The people who appear to have fared best from the deal are those in the US who gobbled up an estimated $3m in fees.

None of this is to deny the desirability of Northern Ireland putting its best foot forward.

But it is important to retain a sense of proportion.

Last week, a PricewaterhouseCoopers report, external indicated that the swingeing cuts expected as part of the British government's Comprehensive Spending Review could lead to Northern Ireland losing 20,000 public sector jobs and 16,000 private sector jobs.

Against that, the website of the US economic envoy, external, Declan Kelly, seeks to make the most of any job-creation announcement within its purview. Its news releases this year detail the creation of about 400 jobs.

The disparity in scale between the probable cull by Westminster and the relatively paltry gains from the US makes one thing crystal clear: those who expect an economic panacea to arrive from the other side of the Atlantic are almost certain to be disappointed.

- Published19 October 2010

- Published19 October 2010