Government looks for ways to deal with the past

- Published

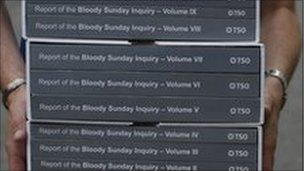

A man carries a copy of the long-awaited Saville report

2010 saw the Bloody Sunday Inquiry finally reporting after 12 years of deliberations and just under £200m in expenditure.

In 2011, two more inquiries are due to report and the government is expected to make a decision on the controversial case of the murdered Belfast solicitor Pat Finucane.

But when it comes to dealing with the past more generally, should we give up on expensive lawyers and hand the job over to historians? And do other countries with troubled histories have anything to teach us?

Northern Ireland Secretary Owen Paterson was impressed when he visited an archive at Boston College where protagonists in the Troubles have recorded their versions of history to be made public after their deaths.

In November, the secretary of state made a speech in which he also referred specifically to the example of Spain, and the Historical Memory Documentary Centre based in Salamanca.

The dictator General Franco ruled Spain after emerging victorious from the bloody civil war of the 1930s.

Today, more than 70 years on, victims of the civil war are still being recovered from unmarked graves across the country.

After Franco died in 1975, Spain tried to brush away its past with a general amnesty - what became known as the pact of oblivion or the pact of forgetting.

That didn't last, though, and three years ago the government passed a new law providing recognition for victims on both sides.

In the city of Salamanca, once Franco's headquarters, the Historical Memory Documentary Centre, makes the records of the war available to the public.

Model

Secretary of State Owen Paterson thinks the centre could provide a model for Northern Ireland.

"Some of the people involved in the events of recent history," he said, "are now getting old, their memories are fading. I think there is merit in trying to capture this information now before it is lost."

Mr Paterson also wonders whether, rather than calling in yet more lawyers, there might be a role for a panel of historians to interpret all the available material with a view to producing an authoritative history of the Troubles.

"I just wonder if historians might not have better skills to try to get to the bottom of what happened in the past than professional lawyers.

"That's one of the things we are looking at and we're consulting widely. I shall continue to have meetings on this matter as it's not easy".

However, some of those examining how to deal with the past aren't so sure. They are concerned the focus on historians may be viewed as a cheaper, easier option by the government.

Denis Bradley co-chaired a consultative group on the past with Lord Eames.

He thinks an official archive could prove important, but historians on their own won't provide the justice many victims crave.

"It's a wonderful idea in a different society - it would be very good to examine the past in Bolivia and a whole lot of other countries.

"But it won't work in Northern Ireland. It won't work as a single factor.

"In itself it's not a bad thing to do, but there is no agreed historical narrative about Northern Ireland, and there probably never will be," he said.

Mr Bradley said survivors of the Troubles want to deal with "much bigger issues, issues like justice, issues like truth, issues about how as a society you come to terms with a very difficult and very ugly past that allows you to move on".

Early in December, the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) chaired a seminar on the past at the Ulster Hall in Belfast.

The CAJ's Director Mike Ritchie said giving the job of dealing with the past to historians, not lawyers, won't fulfil the government's responsibility to properly investigate deaths under the European Convention on Human Rights.

"An archive is fine as long as it isn't a way of trying to avoid responsibilities in other departments," he said.

"That's where finding the truth and giving families acknowledgement about what happened in the past is a responsibility of the government and they need to address that issue."

The Northern Ireland Office is due to spell out its ideas on the past in more detail some time next year.

The secretary of state said there probably would not be one big announcement, or an all encompassing arrangement.

Instead he's talking about tackling the past in different ways, in the hope that the various pieces of the jigsaw fit together.

- Published20 December 2010