Bloody Sunday the reason for Queen's Croke Park visit

- Published

In the shadow of Slievenamon, a mountain celebrated in folk songs, lies an unremarkable little place.

Grangemockler on the road between Kilkenny and Clonmel has a shop, a pub and little else that would encourage a passing motorist to pull in.

But in the graveyard of St Mary's Church is the body of a man revered by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA).

A man whose death at the hands of British soldiers and Irish policemen in Croke Park more than 90 years ago is part of the folklore of the organisation, and much of the reason why the Queen's visit to GAA headquarters has aroused such interest.

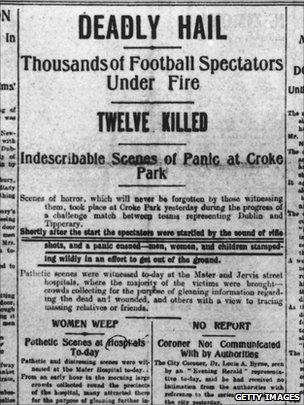

The Dublin Evening Standard reacts to the killings on Bloody Sunday

Mick Hogan was a Tipperary footballer. He was one of 14 people to die in the stadium when regular soldiers, Black and Tans, members of the Royal Irish Constabulary and the Dublin Metropolitan police surrounded Croke Park and fired on people attending a match there on Sunday 21 November 1920.

It was the original Bloody Sunday. A key moment in the Irish War of Independence.

It was a brutal episode in what had already been a violent day.

Earlier, IRA assassination squads under the control of the organisation's leader Michael Collins had knocked on doors around Dublin and shot dead 14 people, including 12 men considered by Collins to be the backbone of the British intelligence system in the city.

The stated intention when the troops and police turned up at Croke Park later that afternoon had been to detain and search the thousands of fans leaving the game between Tipperary and Dublin which was being staged as a fundraiser for republican prisoners.

The soldiers claimed they had been fired on first, but historians suggest there is little evidence to support the allegation.

After 90 seconds of sustained fire, 13 people were dead, shot or crushed and 80 were injured. Another person was to die later.

Mick Hogan, 24, was the only player to die. It was Monday before news of the killing reached his mother in her County Tipperary home.

I travelled to the county to meet his nephew, Michael Hogan, in the graveyard of St Mary's.

"My own father was only 14 when his brother was shot dead. He didn't talk about it much, I suppose he didn't have a great recollection of it, he was only a child at the time," he said.

"It was a tragedy for the family at the time, he was missed in the house.

"Bloody Sunday was a big tragedy for the family, but sure if it hadn't been him, it would have been somebody else."

The GAA

The Hogan Stand, named for the dead footballer, is a key part of the 80,000-seat Croke Park, redeveloped in the 1990s at a cost of 260 million euros.

It is the stand where the dignitaries sit; it is the place where the cups are presented; it is considered by many fans to be the best seat in the house.

The GAA is a sporting and cultural organisation, but its roots lie in the nationalist revival and political upheaval at the end of the 19th century.

Dr Paul Rouse is a history lecturer with a particular interest in the association.

"It was the decade of land and freedom when Irish nationalists were pushing for home rule, where the country was torn apart by land war in that decade.

"You see it (the GAA) in the context of the 1880s and the development of an organisation which was more than just a sporting organisation, instead it was also an assertion of Irish nationalism and Irish national identity."

The GAA has changed a lot in recent years.

It dropped a ban on members of the security forces and changed its rules to open up Croke Park for soccer and rugby.

In 2007, there was an emotive moment when God Save the Queen echoed round the ground before a rugby international between England and Ireland.

Croke Park witnessed history when Ireland hosted the English rugby team in 2007

'A step forward'

Back in Grangemockler the children of the parish are at their GAA training night. Overseeing it are officials of the club, men like chairman Johnston Lyons and Mick Pender.

I asked them for their view on the Royal visit to Croke Park. They conceded that some of the older people from Mick Hogan's home town are not keen, but the consensus, particularly amongst younger people, is that it is to be welcomed.

"It could have been very easily avoided. She could have gone to a dog show, or something very non-controversial, but they've tackled it head on," said Mick Pender.

"I think it's a good thing, it shows where we're moving on to. We've enough troubles in other areas, we don't need to complicate things by making a big deal out of other issues."

"Mick Hogan is held in very high esteem around here," said Johnston Lyons.

"My late father used to talk about what happened a lot. He used to describe the funeral and how they met him off the train. The memories are instilled round here, I think he'll always be remembered.

"This is a step forward. I think they want to put it in the past too and move on."

But perhaps Mick Hogan's nephew Michael puts it best.

He says he wasn't keen on the playing of God Save the Queen in 2007, but he has now relaxed about the visit of Queen Elizabeth to the spot where his uncle was killed.

"I find that in the present situation I welcome Queen Elizabeth to Ireland and I've no objection to her going to Croke Park.

"We have to move on. Bloody Sunday happened 90 years ago."