NI corporation tax rate cut funding options explored

- Published

The debate on corporation tax has some way to go, but judging by what First Minister Peter Robinson told the Assembly on Monday, the argument is not whether Northern Ireland should have the power to lower its rate, but what price it should pay for that power.

The Westminster government is currently consulting on a paper it produced outlining the costs and benefits of allowing Northern Ireland to set its own business tax rate. That the Treasury should even consider allowing this debate is a seismic shift, but Northern Ireland's politicians are keen to ensure they maximise any benefits while minimising any costs.

The reason it will cost comes down to European law which stipulates that regions cannot use taxation as a form of hidden subsidy. So, any reduction in tax rates for Northern Ireland must be paid for by a corresponding and equivalent cut in the block grant.

It is this equation that leads critics of the proposal to the conclusion that businesses will benefit while public services will lose out - cutting hospital beds to fund tax cuts for bankers is hardly a popular measure.

But its supporters say that this missing the entire point of the the idea. By cutting business rates, they argue, there will be more jobs created and the greater wealth generated will more than compensate for the amount lost in the block grant. You take a slice out of the cake, but the cake itself gets bigger thereby compensating for the missing slice.

The argument now at a political level - even though the Treasury has yet to say yes in principle - is over the size of that initial slice and the formula used to calculate its size.

At Question Time on Monday Peter Robinson gave a few hints about how he's trying to bargain the price downwards. He suggested the bigger tax revenues from increased employment and greater spending in the local economy should be offset against the initial cost of the reduction in business tax take to the Treasury. He even suggests that any reduction in welfare payments should be included in this new equation.

He also points out that Northern Ireland can reduce the potential cost by delaying implementing the reduction - perhaps by up to two years. This, he argues, would allow investment to start with companies safe in the knowledge that the tax cut would be in place by the time they expected to be making profits.

'Different beast'

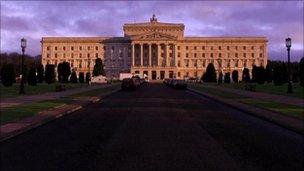

Agreeing a formula is already causing tension between Westminster and Stormont

The other way of easing the pain, he suggests, is by phasing the reduction over a number of years. Like the delay, this signals the ultimate destination while spreading the cost of getting there.

All of this discussion and negotiation is taking place as the clock ticks towards the end of the Westminster government's consultation on 24 June.

Agreeing a formula for calculating the reduction in the block grant will be a huge headache and is already causing tension between Westminster and Stormont. The Treasury paper concedes some ground on consumer taxes like VAT, accepting that these could be offset against the cost. But it says nothing about income tax receipts, which could be much greater and persuading them to include an allowance for reduction in benefits may be a bridge too far.

A delayed start to the reduction may make sense as it takes time for inward investment to move, and even longer for profits to be made. Phasing-in could also make sense, but agreeing a fixed baseline from which to make calculations would be important. Phasing might provide the Treasury with the option of tweaking the baseline on a year-by-year basis which could increase the cost to Northern Ireland.

The danger for the Northern Ireland Executive is that it over-negotiates and winds up with nothing. Alex Salmond's stunning electoral performance in Scotland has made this an issue that could create huge constitutional problems for David Cameron's administration.

The previous steer from the Treasury to the BBC was that Northern Ireland was likely to receive the power to vary its business tax, but that exemption would be unique and Scotland would not be offered the same choice.

The recent row between Holyrood and Westminster over the Chancellor's special levy on North Sea oil producers demonstrates the magnitude of the issues at stake. Northern Ireland has a tiny business tax base, Scotland is a different beast altogether.

If the negotiations get too messy and the politics too dangerous the Treasury's previously benign sentiments could very quickly turn negative.

- Published1 June 2011

- Published29 May 2011

- Published13 March 2011