The paramilitary who became a peacemaker

- Published

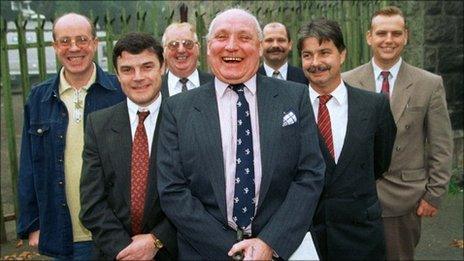

Gusty Spence (centre) pictured with loyalist political leaders in 1994

When Gusty Spence was given the task of announcing the loyalist ceasefires in 1994, there was a symmetry to his role.

In the 1960s, he had been a founding father of the modern UVF, an organisation which would subsequently murder hundreds of people, mainly innocent Catholic civilians.

Almost three decades later, he sat before the world's media, telling them that the UVF and another loyalist organisation, the Ulster Defence Association, were going on ceasefire in response to the IRA's cessation.

In his statement, he said that loyalists wished to express their "abject and true remorse" for their role in the Troubles.

A man who shared responsibility for starting the conflict was now taking a lead role in the first steps towards its conclusion.

Military experience

Gusty Spence was born in 1933 in the loyalist heartland of the Shankill Road.

His father had been a member of the first incarnation of the UVF, who were formed to fight Home Rule and whose members would subsequently make an enormous contribution in the First World War.

Spence himself joined the military police before leaving due to ill-health in 1961.

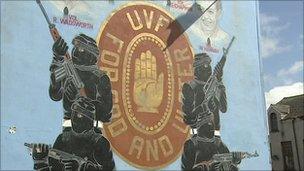

The UVF was responsible for the murders of hundreds of people during the Troubles

His account of how he became involved with the UVF begins in 1965 when he claimed to have been approached by two men, one of whom was an Ulster Unionist Party member of the Stormont parliament.

He said they told him the UVF was to be re-established and that they wanted him, because of his military experience, to play a role in it.

Despite the organisation's claims of having declared war on the IRA, it was Catholic civilians who bore the brunt of its violence.

In June 1966, 28-year-old John Scullion became the first victim of the modern Troubles, when he was shot by the UVF in the Falls Road area.

Spence was one of three men arrested in connection with the killing but the charges were dropped.

Political settlement

Later the same year, 18-year Peter Ward, a Catholic barman, went for a drink in a pub on the Shankill Road - not an unusual course of action in the days before the Troubles fully flared.

Spence, who was in the bar and overheard Peter Ward's conversation, was sentenced to life for shooting him dead as he left.

He spent the next 18 years in prison, apart from a brief hiatus in 1972 when he escaped after being given parole to attend his daughter's wedding.

During his four months on the run, he donned dark sunglasses to give a statement to the media as the UVF's commanding officer.

Once recaptured and back in prison, Spence is described as having realised that the Troubles would eventually have to end with a political settlement.

He encouraged his fellow UVF prisoners to think similarly and following his release from prison due to ill-health in 1984, he was credited with having a significant influence on the nascent political wing of the UVF, the Progressive Unionist Party.

Its charismatic leader David Ervine would later hold Spence up as his role model, as someone who was capable of having a more strategic vision of where loyalism was headed.

As part of that process, he re-examined his own identity, learning the Irish language and defining himself as an Ulster Irishman who was also British.

In 2007, Gusty Spence announced that the UVF would decommission its weapons

Unwavering support

Despite the dialogue within loyalism, the UVF continued its campaign of sectarian violence until 1994 when Spence issued the historic statement on behalf of the so-called Combined Loyalist Military Command.

Members of the UVF continued to be involved in sporadic violence in subsequent years but Spence's support of the peace process was unwavering.

When the organisation announced in 2007 that it was decommissioning its weapons and would exist only as a civilianised organisation, Spence was again called upon to make the landmark statement.

As late as 2010, when members of the UVF were blamed for murdering a man near Spence's childhood home on the Shankill Road, he again intervened, telling the BBC that the organisation should disband once and for all.

It was his last contribution in an era which he had helped to define.

- Published9 November 2010

- Published22 June 2011