Ryan versus The White Star Line

- Published

The Titanic was owned and operated by the White Star Line, but two high profile inquiries found the company was not to blame for the disaster.

Ryan v White Star Line

In a true David and Goliath battle, it took an elderly Irish farmer to finally prove White Star's negligence.

The business of taking passengers across the Atlantic was a cutthroat one, and the White Star Line was engaged in a constant battle for supremacy with its nearest rivals, Cunard.

Where Cunard focused on speed, with its sleek liners Lusitania and Mauretania, White Star went for size and luxury, providing even its steerage (third class) passengers with unprecedented levels of comfort on the crossing.

As Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the White Star Line, told the American inquiry into the disaster, he had put no upper limit on the cost of production of Olympic and its even bigger sister ship the Titanic.

"All we ask them to do is to produce us the very finest ship they possibly can; the question of money has never been considered at all," he said.

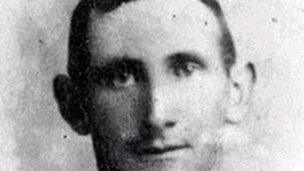

For the likes of Patrick Ryan, the 29-year-old son of a County Limerick farmer, a steerage ticket on the Titanic symbolised a new life in the New World.

He had a job waiting for him in the New York Police Department, but he was one of the many who didn't make it to the lifeboats. His body was never recovered.

Patrick Ryan, lost at sea.

It was a tragedy for his elderly father, Thomas Ryan, who inhabited an entirely different world to that symbolised by the wealth and opulence of the White Star Line.

<bold>The British inquiry</bold>

The American inquiry into the loss of the Titanic began on 19 April 1912, just a day after the Carpathia docked in New York with the survivors.

It concluded on 25 May and found no negligence on the part of the White Star Line.

The British Board of Trade inquiry began on 2 May and was led by John Bigham, Viscount Mersey, a prominent barrister who was asked to come out of retirement for the purpose.

A flavour of Mersey's attitude to the inquiry comes from his response to a question about whether or not he intended to hear from all classes of passengers, Mersey responded that "… survivors are not necessarily of the least value."

In the event, only two passengers were called to give evidence and both were travelling in first class. They were Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line, and Sir Cosmo Duff, who was fighting accusations that he bribed his way onto a lifeboat and had not turned back to rescue those in the water.

"This decision is shocking" says Sean Molony, author of The Irish aboard Titanic; "It means you're confining yourself to hear what people with vested interests had to say, and they will defend their interests.

"Lord Mersey was not inclined to look at the big picture … that would have handed a commercial interest to their [White Star Line's] competitors."

The British Inquiry did find that the Titanic's captain, Edward Smith, had been going too fast and that the lifeboats had not been filled before being lowered, but it was made clear that "negligence cannot be said to have had any part." The White Star Line was not liable.

In the judgement of the senior surviving Titanic officer and hero of the sinking, Charles Lightoller, the American inquiry was a "farce" and of the British one he said: "it was very necessary to keep one's hand on the whitewash brush."

<bold>The wrong sort of litigant</bold>

It was into this climate of vested interests closing ranks that Thomas Ryan stepped. His only interest was in securing justice for his son, and the fact that he was pitting himself against some of the richest and most powerful men in the land, in doing so seemed not to deter him at all.

Ryan sued the White Star Line for damages over the death of his son, alleging that the company was negligent.

For seven days, in June 1913, Thomas Ryan went to the Royal Courts of Justice in London in an attempt to bring the White Star Line to account for the tragedy.

The White Star Line was well defended and had been cleared by two inquiries already. In addition, each ticket bore an extraordinary disclaimer that stated:

"Neither the ship owner, agent, or passage-broker shall be liable to any passenger carried under this contract for loss, damage, or delay to the passenger or his baggage arising from the act of God, public enemies, arrests or restraints of princes, rulers, or people, fire, collision, stranding, perils of the sea, rivers, or navigation of any kind, even though the loss, damage, or delay may have been caused or contributed to by the neglect or default of the ship owner's servants or other persons for whose acts he would otherwise be responsible."

This effectively stated that the White Star Line could not be held liable even if the sinking was the White Star Line's fault.

On this point, Ryan's case was upheld, because his son Patrick and two friends had been issued just one ticket between them.

It was successfully argued that Patrick had not seen the ticket, so couldn't have read the disclaimer. Crucially, Justice Bailhache also found that the wording on the ticket was in contravention of British Board of Trade regulations, which meant that the White Star Line's blanket disclaimer for negligence was now worthless.

The case was a civil action and was heard before a special jury, and they found that the White Star Line was negligent in respect of the speed of the Titanic, which did not slow down despite at least three warnings of ice.

<bold>£100 for a life</bold>

At the end of case, Thomas Ryan was awarded £100 for his son's death - the equivilent to one year's wages.

In addition to bringing the White Star Line to account in the death of his son, Thomas Ryan achieved another far-reaching victory, setting a precedent in consumer contract law that protected rights for passengers.

Disgraced and publicly shunned, Bruce Ismay resigned from White Star Line in 1913.

In response to the tragedy, the White Star Line voluntarily retrained its crews in lifeboat management and reduced the length of shifts for crew members. They also paid for the funeral costs of 150 victims recovered from the Atlantic.

It is perhaps important to point out that the attitude of the White Star Line was not unusual for its time, and in being found to be negligent the company appears to have gone to some lengths to make amends.

"It is a commonly held myth that White Star line stopped the crews' wages the day Titanic sank," says Molony.

"They did stop wages on the 15 April, but this was down to British Board of Trade regulations which were based on old Royal Navy codes … White Star Line, in a show of compassion, actually paid their staff a bonus covering what they would have earned had the journey been completed."

While there is little doubt that the money helped to ease the hardship experienced by many families due to the loss of a loved one on Titanic, it is the right of passengers to be treated equally before the law that was the outstanding achievement made possible by the determination of Thomas Ryan, the farmer from County Limerick, who fought the White Star Line and won.