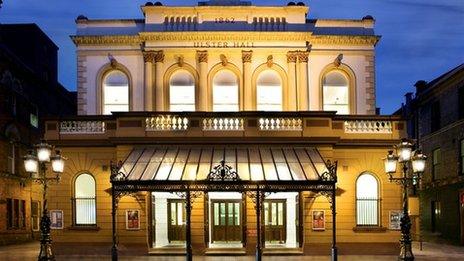

The Ulster Hall: Belfast's window on the world

- Published

The Ulster Hall is 150 years old

For 150 years, the Ulster Hall has been at the heart of Belfast's cultural life.

It has witnessed the changes across Northern Ireland and the world, since 1862. The Grand Dame, as it is fondly known, has housed protest speeches and peace gatherings, rock legends, boxing matches and classical concertos.

Over the years it has played host to a diverse range of personalities: from the son of an American slave to the Dalai Lama and from Charles Dickens on his early literary tours to Led Zeppelin and their first-ever performance of Stairway to Heaven.

Robert Heslip, heritage officer for Belfast City Council said the Ulster Hall was "a window to the wider world for people in Belfast; it was the TV of its age".

"It was designed as much for working class labourers as it was for wealthy socialites," he said.

The Belfast Newsletter on 13 May 1862 described it as a place "the rich and the poor, the manufacturer and the sons and daughters of toil, may meet together beneath the arched roof of the new hall, to listen to sweeter sounds and more melodious strains than machinery can produce".

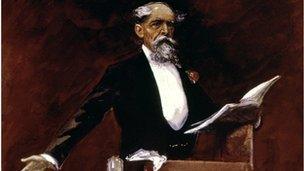

Victorian trailblazers

<link> <caption>Charles Dickens,</caption> <altText>More about Charles Dickens</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/dickens_charles.shtml" platform="highweb"/> </link> who brought literature to the masses on his pioneering literary world tours, had entertained a small crowd in Belfast in 1858, but the newly built Ulster Hall allowed him to perform for a much larger audience - and in the process, sell many more tickets.

In 1867 he read from David Copperfield and A Christmas Carol, and he returned again in 1869.

The great storyteller noted that Belfast was a "fine place with a rough people" and "a better audience on the whole than Dublin".

Charles Dickens noted that Belfast was a "fine place with a rough people"

Historian John Gray said that one reason for the Ulster Hall show was that Dickens "really enjoyed performing, and was, rather unusually for an author, a great performer, but also - he desperately needed the money".

In 1874, The Ulster Hall hosted a controversial speech which, according to historian of science Frank Turner, sparked "perhaps the most intense debate of the Victorian conflict of science and religion."

It was delivered by physicist John Tyndall - the man who would later <link> <caption>explain why the sky is blue</caption> <altText>Read more about John Tyndall</altText> <url href="http://understandingscience.ucc.ie/pages/sci_johntyndall.htm" platform="highweb"/> </link> - to the British Science Association.

Tyndall claimed that matter could create life on its own and that cosmology (the study of the universe) was the domain of science not religion.

The speech came to be known as The Belfast Address and would incur the wrath of religious leaders.

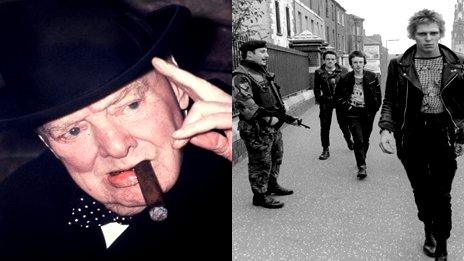

Locked out

The Ulster Hall is not just famous for those who performed within its walls, but also for those who were barred from entry.

In February 1912, Winston Churchill, who was due to talk in the Ulster Hall in favour of Irish Home Rule, found himself locked out.

Unionists, who favoured direct rule by Westminster, filled it wall to wall and refused to move. To add to the humiliation, the men who locked him out had been inspired by Churchill's own father.

Twenty-six years previously, Randolph Churchill had rallied supporters against Home Rule in the very same hall.

He had urged unionists not to let Home Rule come upon them "like a thief in the night" and famously told his supporters that "Ulster will fight, and Ulster will be right".

The hall's place at the heart of Unionism is epitomised by the Ulster Day rally on 28 September 1912.

Unionists gathered here before marching to City Hall to sign the <link> <caption>Ulster covenant</caption> <altText>see the Ulster covenant</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/ZB_INs3LRqq1qYNnhuN6QA" platform="highweb"/> </link> - a petition to <link> <caption>oppose Home Rule,</caption> <altText>find out about Ulster's resistance</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/easterrising/prelude/pr04.shtml" platform="highweb"/> </link> which contained almost half-a-million signatures.

At the height of the Troubles in 1977, another lock-out would bring more change to Northern Ireland.

Punk band The Clash were due to play, but when insurance was cancelled for the gig, hundreds of disappointed fans were left outside the Ulster Hall with nothing to do and nowhere to go. They were soon met by riot police and violence erupted.

Terri Hooley, whose Good Vibrations record label galvanised the Northern Irish punk music scene and would later launch local band <link> <caption>The Undertones</caption> <altText>listen to the Undertones</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/music/reviews/jnzb" platform="highweb"/> </link> to a worldwide audience said it may have been "the only riot of the Troubles where Catholics and Protestants were fighting on the same side".

"This was a time when the IRA were blowing the city apart and loyalist gangs were killing Catholics - punk was a very united force against that - to be a punk was to be different from the past. The kids were fed up with the Troubles for the first time and the Ulster Hall would have played a big part in that," said Terri.

Winston Churchill and The Clash were both locked out of the Ulster Hall

Many believe that what became known as the Battle of Bedford Street kickstarted the punk movement in Belfast.

Led Zeppelin debuted Stairway to Heaven at the Ulster Hall. Although the nonplussed audience were presumably unaware of the moment of history they were watching. John Paul Jones, <link> <caption>the band's bassist, recalled</caption> <altText>Listen to Led Zeppelin talking about Stairway to Heaven.</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio2/soldonsong/songlibrary/indepth/stairway.shtml" platform="highweb"/> </link> that the crowd were "all bored to tears waiting to hear something they knew".

The Rolling Stones only managed to play around 13 minutes of their set before hysterical fans broke up the show. The hall was so packed that fainting girls had to be passed overhead and onto the stage, before being removed from the hall - some of them strapped to stretchers to contain their excitement.

A changing world

On Easter Tuesday 1941, Irish singer Delia Murphy was performing in the Grand Dame when Belfast was blitzed by German bombs.

As the city turned to an apocalyptic scene outside, Murphy played on, entertaining the crowd who could do nothing but wait to see what morning would bring. Around 900 people were killed that night, and more than half of the homes in Belfast were destroyed.

During World War II, Belfast was the first port for American soldiers before the battlefields of Europe. The Grand Dame was an important centre for entertaining the troops.

They jitterbugged the nights away with such enthusiasm, that on one occasion the floor gave way. So important was that dance floor to the morale of the troops the American Embassy paid for a new solid oak replacement.

Rinty Monaghan and Barry McGuigan both won titles at the Ulster Hall

Unfortunately, the American floor was not quite strong enough to match the dancing force of the fans that flocked to support Dexy's Midnight Runners in 1980.

The floor again collapsed as the crowd danced to Come on Eileen, but they simply moved to the back of the hall and kept the show going.

The Ulster Hall hosted many high profile boxing bouts including Rinty Monaghan winning his Ulster title there - he would later become flyweight champion of the world.

The promoter of many of his fights in the hall was Clara "Ma" Copely.

This 22 stone woman from a circus family was awarded a silver fruit bowl by the patrons of the Ulster Hall "for services rendered to the sport of boxing."

Rinty Monaghan paved the way for another slight but powerful boxer: Barry McGuigan, who won his first Ulster, British and European titles in the Ulster Hall in 1983 and 1984.

The Grand Dame of Bedford Street has stood for 150 years, and watched the changes in Ireland, Britain and the world.

Just like its founders said "it will stand without a compeer, at least till the generations now living will all have passed away. This building has been well named The Ulster Hall."