Who are the Orangemen?

- Published

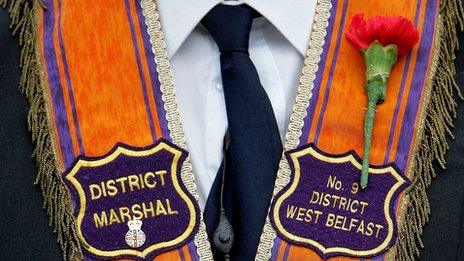

An Orangeman's collarette

If you're not from Northern Ireland, you may be wondering what on earth the 'marching season' is all about.

Who are these men in bowler hats and orange sashes?

Most Orange Order parades pass off peacefully but the rest of the world has often only seen images of those that don't.

So who is marching and why, and why do some people sometimes object to parades?

Marching for King Billy

The Orange Order is a 'fraternal' organisation, named for William of Orange, the Protestant Dutchman who seized the thrones of Catholic King James II back in the 'Glorious Revolution' of 1688.

Two years later, 'King Billy' saw off James for good at the Battle of the Boyne, near Dublin. He is revered by the Orange Order as a champion of his faith and the man who secured the Protestant ascendancy in Ireland.

The 'marching season' is a period of events from April to August, with the highpoint on 12 July when Orangemen march to commemorate William's victory.

For many Catholics, these marches are triumphalist and sectarian - a means of very publicly 'rubbing in' a historical wrong - with some traditional Orange routes passing through or by staunchly Catholic and nationalist areas.

Some of those marches have been re-routed but some remain contentious. At Garvaghy Road in Portadown, County Armagh, Orangemen make an annual protest at not being permitted to parade along the route they want to take.

Efforts are made to reduce problems around contentious parades with re-routing and highly visible policing.

Becoming Orangefest

The Orange Order itself has also attempted to move with the times, rebranding the 12 July celebrations 'Orangefest' in a public relations charm offensive that presents the day as a fun and inclusive dash of local colour. There was even, briefly, a superhero mascot called Diamond Dan.

It's a canny decision, with membership of fraternal societies generally in sharp decline. The Orange Order's secrecy, ceremonies and archaic titles - all distantly derived from Freemasonry - smack of a bygone age. While staunchly loyal to its traditions, the Orange Order also understands it must reach out to a new generation.

"It's full of tradition and history, but you have to make that fit with young people," says Mark McKinty, a 24-year-old Orangeman who joined after seeing Easter parades in Spain and religious festivals in India.

"I realised that parades are used to express culture and faith … I've seen first-hand how that works."

It is undeniably a spectacle worth seeing, although you'll hear it long before it appears.

Most lodges march with a band that sometimes includes the occasional enormous Lambeg drum, one of the loudest acoustic instruments in the world.

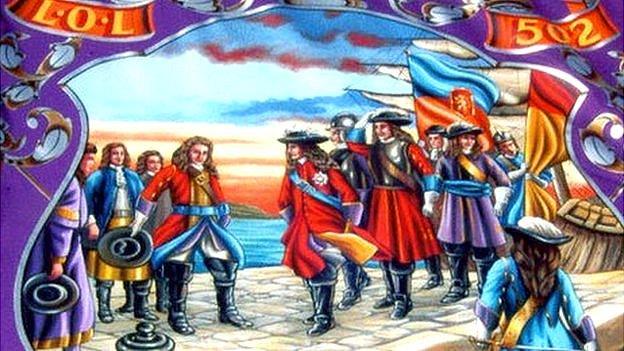

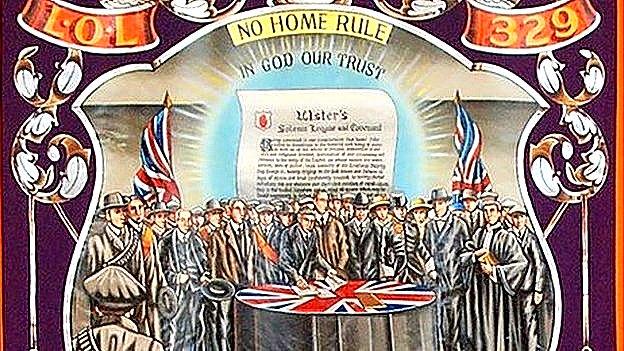

The marchers carry a colourful forest of banners, flags and pennants depicting an array of Protestant symbolism, including iconic scenes from Orange history such a King Billy crossing the Boyne or the 36th (Ulster Division) on the Somme.

This banner depicts William of Orange arriving at Carrickfergus, in what is now Northern Ireland. He brought with him the largest invasion force Ireland has ever seen and used it to defeat James II at the Battle of the Boyne.

This banner depicts William of Orange on his distinctive white horse being hailed by his troops at their camp before the Battle of the Boyne. James II was defeated, ending his hopes of taking back his throne.

This banner depicts the cottage of Dan Winter, one of the founders of the Orange Order, and is reputed to be where the decision was taken to found a brotherhood for all Protestants, named for William of Orange

This banner depicts the signing of the Ulster Covenant in September 1912. The covenant was a protest against the Third Home Rule Bill, which proposed to give Ireland self-government within the United Kingdom. Protestants generally, and Orangemen in particular, opposed the bill.

This banner depicts the 36th (Ulster) Division on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916. Of the nine Victoria Crosses awarded to British soliders on that day, four went to men of the Ulster Division. Regimental mythology has it that Orangemen in the division charged wearing their sashes.

A few bands still tout the provocative emblems of loyalist paramilitary groups.

The nature of the parade inevitably throws together those who envisage a peaceful future with those who hark back to a darker past. One of the problems confronting the Orange Order is that many cannot easily tell where the line falls between the two.

Perhaps because of this, Orangefest is at pains to be inclusive, making much of lodges from as far afield as Togo, Canada and Ghana.

Perhaps just as interesting is the social cross-section of Northern Ireland's unionists and Protestants who march or come to watch the marchers.

Peep O'Day to PM

The Orange Order has its origins in the 18th century Protestant rural vigilantes, like the 'Peep O'Day Boys', who were set up to fight their Catholic equivalent, the Defenders.

The Order itself was founded after the so-called Battle of the Diamond, a skirmish that took place in County Armagh in 1795.

"The message went out about this organisation they would set up to defend Protestants," says Clifford Smyth, a historian of the Orange Order.

"Its most important feature was that it brought together people who didn't necessarily get on together, like Presbyterians and Methodists, so it unified the Protestant community."

By the 20th century, the Order had pervaded the highest echelons of society. Every prime minister of Northern Ireland, from Partition in 1921 to the return of direct rule in 1972, was an Orangeman, as are a number of current ministers in the Northern Ireland Executive.

The Order still sees itself as a unifying force among Protestants, and as such the lodges and their marches throw together people from very different parts of the social and political spectrum.

Bowlers and sashes

The Orangemen's bowler hats, sashes and white gloves are still very much in evidence, but these are expensive and times are tight.

The orange sash has been largely replaced by the cheaper 'collarette' and is the only compulsory item of uniform, usually worn over a suit and tie.

The bands, by contrast, have colourful uniforms, finished with tassels, braid and buttons galore.

Union flags are also highly visible, particularly among the spectators. The union with the rest of the United Kingdom is a cornerstone of the Orange Order - a major bone of contention between the marchers and the nationalists who would like to see a united Ireland.

At the Belfast parade, the biggest of the 18 major 'Twelfth' parades across Northern Ireland, the marchers snake from Carlisle Circus in the north, via the Cenotaph at City Hall, to Barnett's Demesne, better known as 'The Field', in the south, where spectators, bands and Orangemen crowd together to picnic, drink and listen to speeches.

The future's bright?

But even with the rebranding, the PR push and the undeniable spectacle, the question remains: can the celebration of such a deeply contentious date, organised by a group that actively champions one community to the exclusion of another, ever be anything other than divisive? Put more simply, is the future bright for the Orangemen?

"For a tourist, the cultural, historical and religious aspects of the parade are what they should see," says Harold Weir, a 42-year-old Orangeman.

"We have been trying to get young people to learn and have respect for their own culture and other peoples'."

Dr Eric Kaufmann, an expert on the Orange Order, says the Order's future probably depends on the direction Northern Ireland itself takes.

"Their ideology is important. Can they work in a post-peace process Northern Ireland? Oddly enough I think it does work. If multiculturalism is accepting different cultures, then they slot right into that model … [but] they're definitely not going to work well in an integrated rather than a multicultural Northern Ireland."