Enniskillen bombing: 'The injuries were horrific - I knew it would get worse'

- Published

Eleven people were killed on the day and a 12th man died 13 years later from his injuries

It was a Remembrance Sunday much like any other. As in previous years, I was providing a live commentary from Belfast Cenotaph for the Downtown Radio Poppy Day programme.

As Elgar's Nimrod was played by the military band and wreathes were being laid, I felt a finger lifting the headphones off my ears and heard my radio engineer whisper that I was to contact the newsroom urgently.

I looked at him with incredulity. Surely the newsroom was aware that I was broadcasting live on air?

What could possibly necessitate me to break off to make contact with the office? Something in the engineers face convinced me to do so.

The duty editor told me in very few but deliberate words: "There's been an explosion at the war memorial in Enniskillen and there are multiple casualties. You need to go….now."

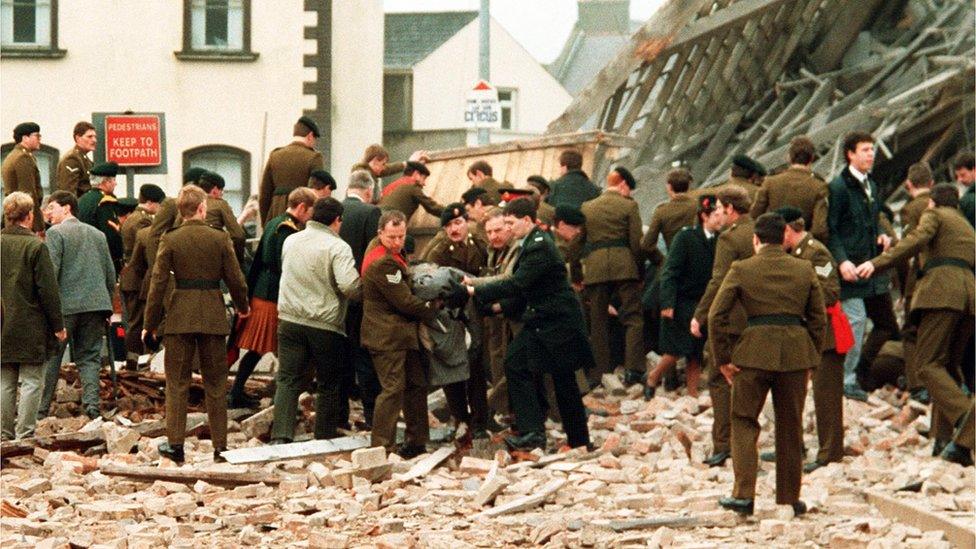

People fled from the scene of the explosion at the cenotaph

I wrapped up the Belfast ceremony as sensitively as I could, jumped in my car and drove off at some speed in the direction of Enniskillen.

This was a time before mobile phones - the only contact I had with the outside world was the car radio in the dashboard.

This was also a time before 24-hour rolling news on radio or television. I scrolled through the channels trying to find a Sunday programme that might carry a news flash.

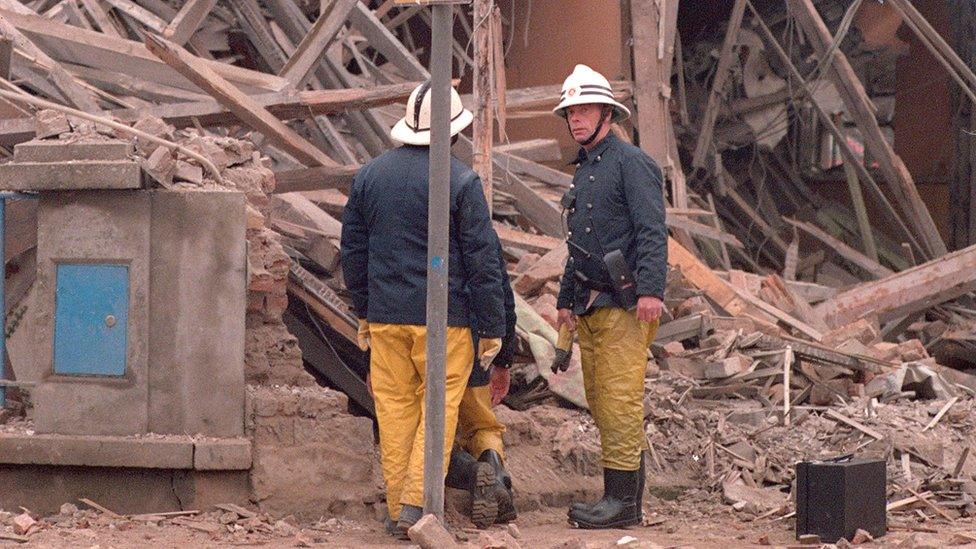

The Poppy Day Bomb brought widespread condemnation

The radio bulletins were reporting that a bomb had gone off at the cenotaph and several people had been killed, many more injured. I knew from the tone and also from gut instinct that the situation would become a lot worse as the day unfolded.

I parked up and went straight along Belmore Street to the scene of the explosion. The dust had settled but the debris was all over the place.

Chunks of masonry - some blood spattered - were strewn across the street. There were people standing around but it was eerily quiet. Even at close quarters, actually standing at the scene of the blast, the enormity of the tragedy wasn't apparent.

'Horrific'

I asked someone where the British Legion organisers could be found and was told to try the hall nearby. I went straight there.

The doors were all open so I walked inside. The premises was deserted. Over-coats were strewn over chairs and gloves and leather flag pole holsters lay around the floor. I called out but no one responded.

I realised instantly the place I needed to be was directly across the river at the Erne Hospital.

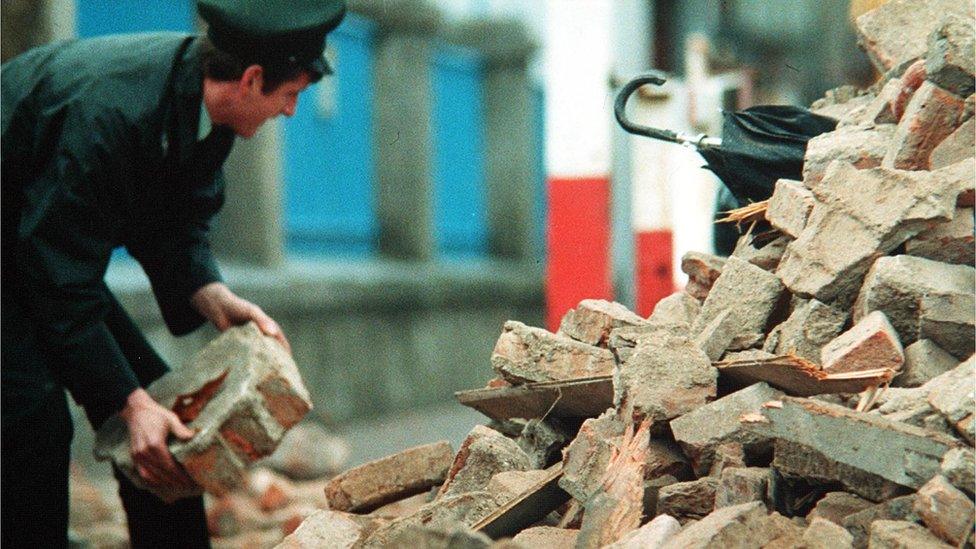

Those who died in the attack were all Protestant and included three married couples along with a reserve police officer and several pensioners

Minutes later, at the hospital car park, I noticed police officers desperately clearing a corner site in the parking area. An Army helicopter descended into the space just yards from where I was standing. I switched on my tape recorder to grab some atmospheric sound.

Within seconds, I heard the sound of wheels rumbling across tarmac and turned to see nursing staff rushing from the hospital building with a stretcher on wheels.

It seemed to be covered in brilliant white laundry but as it trundled past me I saw a grossly swollen head sticking out of the bed sheets. It pulled me up short. This was my first sight of a casualty from the bombing and the injuries were horrific.

A man in uniform digs through rubble at the scene

Inside the small reception area of the hospital there were a few people sitting in chairs or standing in the corridor but there was no screaming or sense of panic.

I found an office with a sign on the door which indicated a senior medical person, so I knocked on the door and found a doctor inside.

I introduced myself hoping he could record a quick interview with me regarding casualties and extent of injuries. In hindsight, it was like asking an air traffic controller to recite a chapter of Shakespeare during the Heathrow rush hour.

Funerals

I went to the reception area, sat down, gathering my thoughts - desperately trying to think about what I should do next, when it occurred to me that I was the only reporter there at that particular time.

As journalists do, I starting asking myself 'where is everybody else and shouldn't I be where they are?'

It was then that I noticed a man standing among a small group of people in one of the corridors leading off reception.

He was tall and his hair was grey, as grey as his once dark suit which was covered in masonry dust. Something urged me to go forward and try to interview him but equally something else prevented me from doing so.

That man, I believe, was Gordon Wilson.

Later that night, after his daughter had died in the rubble holding his hand, he recorded an interview with a BBC Northern Ireland news crew. He was a Christian man and he said he would pray for the bombers who murdered his daughter.

The words that he spoke during that interview went global, touching the hearts of millions, including the Queen.

I was among the first journalists from outside Enniskillen to arrive at the scene of the bombing but within a few hours the world's news media was rolling into town.

I stayed in the County Fermanagh town for most of that week, covering back-to-back funerals for seven of the victims.

A feeling came over me that I had never experienced before. I can only describe it as the effects of grief overload and I agreed with my news editor to come off the story.

I returned to Enniskillen some weeks later to report on a special commemoration service held at the cenotaph attended by the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher attends a special commemoration service at the cenotaph

I have been back to the town on numerous occasions since then for personal and professional reasons and when I do go back, the events of that time 30 years ago are never far from my mind.

- Published8 November 2012