'Titanic violin' sparks heated debate

- Published

Thousands of people viewed this violin at Belfast City Hall over the Easter weekend

A bitter row has erupted over a violin due to be auctioned for a six-figure sum.

The violin is believed to be the instrument whose strings rendered the soothing hymn Nearer My God To Thee as the Titanic sank.

It was saved from the water in 1912 and re-appeared in an attic in Yorkshire seven years ago, according to auctioneers.

There is a passion across the world for the finer details of the Titanic story and enthusiasts are divided about the violin, which will be sold by the specialist auction house Henry Aldridge and Son.

The debate centres on three main points - how did the violin survive, what do documents from the time tell us, and does the instrument simply look too good to be true?

Sceptical

Writer Daniel Allen Butler says the violin cannot possibly have been recovered from the doomed ship's wreckage.

The genuine article would have fallen apart after exposure to the waters of the North Atlantic, he said, and the wood would soon have lost its shine and shape.

Mr Butler contacted three luthiers, professional violin-makers.

After looking at a photograph of the violin, the luthiers scoffed at the idea that it is the same violin that bandmaster Wallace Hartley played on board RMS Titanic.

Violin restorer and dealer, Ken Amundson, put one of his own violins, in its case, in cold, salty water. After an hour of this experiment, the "ribs", or outer curves, of the violin started to come apart.

But violin dealer Andrew Hooker, formerly of Sotheby's, says violins have survived encounters with seawater in the past.

In 1952, an 18th century Stradivari violin was swept out to sea but washed up on shore the next day and could be played again.

Mr Hooker examined the Hartley violin in person and says it has been restored since surviving the Titanic disaster.

"The varnish that's on it now is without a doubt better than the original varnish", he says.

It is perhaps natural to be sceptical about the instrument, given all the ship's musicians drowned in the disaster.

Auctioneer Andrew Aldridge admits as much. He recounts the first call he took from the violin's anonymous owner.

"I thought, hmm, this is interesting," he says.

"As an auctioneer you play devil's advocate, and look for reasons why it's not genuine."

But over the last seven years, a host of experts have helped his company authenticate this instrument.

They included the forensic science service, who found the bodywork still had deposits of salt water.

The violin was in a near-waterproof leather case, Mr Aldridge says, and animal glue, of the kind that held it together, melts when it is hot, not when it is cold.

"These things were not submerged," he says. "They were not covered in water."

Mr Aldridge feels that the naysayers have made his auction house the victims of an "internet campaign".

Second violin?

Mr Aldridge says the violin survived in a leather case, strapped to Wallace Hartley's body, which floated upright in his cork and linen lifejacket for ten days.

When the morgue ship Mackay-Bennett picked the bodies of victims up, they brought Hartley's violin back to land too.

It was sent back to his fiancée Maria Robinson and after 101 years of twists and turns, it has now returned to public view.

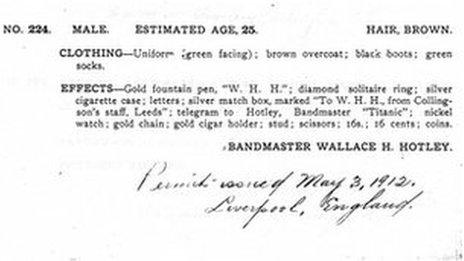

The effects list taken by the Mackay-Bennett crew records things recovered with Hartley's body, from the coins in his pockets to the boots on his feet.

There is no mention in it of the violin or case.

"You are asked to merely take it on faith that this is the Hartley violin," says Mr Butler.

Mr Aldridge said larger items of luggage were frequently not recorded on effects lists because "effects" are small things, like watches.

Hartley's name was spelled incorrectly on the original effects list

"I do think the violin belonged to Wallace Hartley but as a second or third violin," says Tracey Beare. This puts her in the camp of people who think this was not Hartley's main professional instrument.

Mrs Beare is a music teacher and a committee member of the Belfast Titanic Society. The group has not joined the USA's Titanic Historical Society in rejecting the violin outright, but Mrs Beare says that "in her heart of hearts" she does not think the violin was on board.

Mr Aldridge says that Hartley was a "cafe violinist" not a concert-grade musician, and did not have spare money for extra violins.

Henry Aldridge and Son is known worldwide for its expertise and trade in Titanic artefacts.

Recently, a first class menu and plans of the ship went on display in Belfast after passing through the Aldridges' hands.

Andrew Aldridge said: "I'm qualified up to my eye teeth and our reputation is everything bar none. The Is have to be dotted, Ts have to be crossed."

Dedicated Titanic collector Craig Sopin is so sure the violin is the real deal, he would like to add it to his own collection.

"I'm a very sceptical person, but I'm convinced beyond doubt," he said.

The violin will be auctioned towards the end of the year.

- Published2 April 2013

- Published15 March 2013

- Published15 April 2012