Confidential files give insight into Margaret Thatcher's view of Northern Ireland

- Published

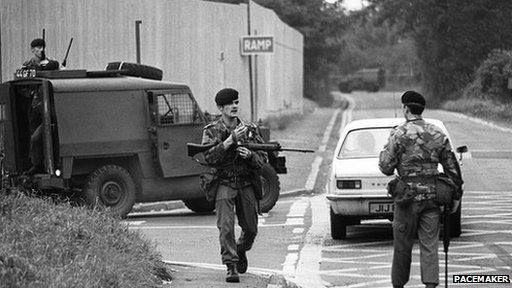

A huge security operation was launched after the escape of 38 IRA prisoners in 1983

Previously confidential files from 1983 released on Thursday by the National Archives in Kew shed new light on the ongoing attempts by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to deal with the political and security situations in Northern Ireland and, in particular, the threat by Sinn Féin to overtake the SDLP as the voice of Northern nationalism.

Sinn Féin's record 13.4% of the regional vote in the June 1983 election and the return of its President, Gerry Adams, as MP for West Belfast came as a shattering blow to Mrs Thatcher, who had returned to power with a renewed mandate after the Falklands war.

Ministers believed that up to a quarter of the Sinn Féin vote was down to impersonation and intimidation.

At a cabinet meeting in June that year, Northern Ireland Secretary Jim Prior warned colleagues that the republicans' success could lead to the destruction of John Hume's SDLP.

'Weakness never pays'

Mrs Thatcher's growing sense of despair at events surfaced at a meeting with Mr Prior in July 1983 when, according to the minutes, she "expressed doubt as to whether we (the British government) could solve the Northern Ireland problem".

The prime minister asked Mr Prior whether he believed Britain should organise a "tactical withdrawal" but the secretary of state thought this would be "utterly wrong" and could lead to civil war.

The files also demonstrate Mrs Thatcher's opposition to the involvement of the European Parliament, which intended to publish a report on Northern Ireland.

At the suggestion that a minister should meet the report's author, Neils Haagerup, Mrs Thatcher retorted angrily: "A meeting would compromise our basic position. I am absolutely against it. Weakness never pays."

Propaganda weapon

In the wake of Mr Adams' triumph, the cabinet authorised the lifting of "exclusion orders" against republican elected representatives but insisted that official replies should be "formal in style" and avoid any hint of friendliness.

Following the assassination of leading Ulster Unionist Edgar Graham by the IRA in December, the cabinet actually considered proscribing Sinn Féin, but then rejected it as likely to give the party a propaganda weapon.

The files reveal Whitehall concern at the republican jail-break from the Maze Prison on 25 September 1983.

Thirty eight prisoners escaped and a prison officer was stabbed to death when guns and knives were used to overpower guards, in what was the worst prison break in British history.

Nineteen of the prisoners were later recaptured.

The Foreign and Colonial Office advised the government to "take every opportunity to limit the propaganda benefit the IRA will try to reap from the outbreak" as they regarded the event as a "propaganda tonic for their flagging morale".

On the report into the escape, which reached her desk five days later, the prime minister wrote: "Even worse than we thought."

Mr Prior came under pressure from unionists to resign but the subsequent report blamed the prison management.

The files contain the first hints of the Anglo-Irish diplomacy that would eventually crystallise in the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement.

Contacts resumed with the return to power in Dublin of Prime Minister Dr Garret FitzGerald at the start of the year and his decision to set up the New Ireland Forum to consider the issue of Irish unity.

In a memo to Mrs Thatcher on 3 October 1983 the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Robert Armstrong, outlined some of the Irish proposals.

These included a commitment to accept Northern Ireland as part of the UK in return for the involvement of Irish judges in North Ireland's judicial system and the use of Irish police for policing in nationalist strongholds "under the tricolour".

The ideas were floated by Michael Lillis of the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs who claimed they had the support of the SDLP leader, John Hume.

Significantly, in view of her earlier assertion that "Northern Ireland was as British as Finchley", Mrs Thatcher seemed interested but sceptical, writing: "We will explore further - but no good will come of it - indeed…I believe the risk of worse violence is very high."

In a further note on the file, Mrs Thatcher asked pointedly: "What happens if one of them (Irish police officer) is shot by a unionist paramilitary group?"

Stumbling block

Sir Robert advised the prime minister that it "would be premature to dismiss Dr Fitzgerald's ideas out of hand".

In the end, however, Irish recognition of Northern Ireland - involving the amendment of Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish constitution and inevitable political risk - proved the stumbling-block for Mr FitzGerald.

The files also contain a report from the British Embassy in Dublin from the newly-appointed ambassador, Alan Goodison, dated 13 December 1983.

He informed the Foreign Secretary, Sir Geoffrey Howe that while many people in the Republic of Ireland were uninterested in Northern Ireland, "underneath there is a basic nationalism" accompanied by a tendency to blame Britain for the "persecution" of the (Northern) nationalist population.

"This is a raw nerve which never sleeps," he added.

The papers also contain a personal note from Mrs Thatcher to Pastor Robert Bain following the murder by a group styling itself the 'Catholic Reaction Force' of three members of his congregation at Darkley Pentecostal Church on the south Armagh border on 21 November 1983.

She described the atrocity as a "despicable and disgusting act".

- Published1 August 2013

- Published8 April 2013