What is the legacy of 1913 Irish strike and lockout?

- Published

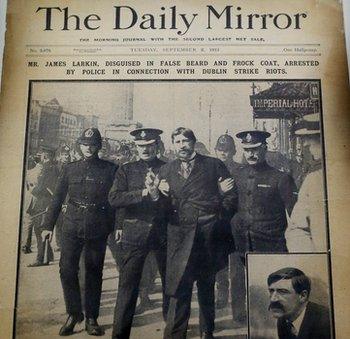

How the arrest of Jim Larkin was reported at the start of the dispute

One hundred years on from the long and bitter Irish labour dispute, the 1913 lockout is generally considered an heroic failure.

A five month stand-off, involving 20,000 workers ended before their main aim of trade union recognition, had been achieved.

Yet, immortalised in bronze, two of its major figures, James Connolly and 'Big' Jim Larkin still stand in Dublin city centre.

Symbolic

Last week, thousands filled Dublin's O'Connell Street to commemorate the strike and lockout.

Irish President Michael D Higgins kneeled to place a wreath at the feet of union leader Larkin's statue.

For the man on the plinth this would have been unimaginable. That the president should be involved in the ceremony shows the resonance the lockout carries a century on.

But what, if any, were its practical consequences? Did the 1913 lockout mark a watershed in Irish industrial relations? Or was its significance ephemeral and symbolic?

For Padraig Yeates, historian and author of Lockout, the labour movement's survival alone contributed to growing union involvement.

Despite many returning to work, the cause was not broken. In fact, the unions that Larkin originated (ITGWU and FWU) still exist, albeit merging in 1990 to create SIPTU (Services Industrial Professional and Technical Union). Crucially, Connolly and Larkin had established a belief in collective industrial action.

From proscribed organisations in 1913, by 1919 they claimed 270,000 members, partly as a result of concessions made to prevent strikes during the war.

Today, around 37% of workers (633,000) in the Republic of Ireland are members of a union.

However, such engagement hasn't been borne out politically. Ireland is one of few European countries where there is still no collective bargaining and it remains a divisive issue for the Fine Gael /Labour coalition.

Leadership

Padraig Yeates believes the centenary of the lockout could serve to bring union concerns to the fore and add fresh momentum to Labour's push for statutory rights to collective bargaining.

Union representatives like Shay Cody, general secretary of Impact, have already invoked the lockout in relation to companies like Intel and Ryanair, claiming that a lack of collective bargaining was tantamount to limiting freedom of association, as occurred in 1913.

With so many young people out of work and such a high proportion on part-time or zero hours contracts, Yeates expects a swell in union support as workers seek greater job security and improved pay and conditions.

With no obvious current figurehead for the union movement, he adds, young people are looking again to Larkin and Connolly as examples of muscular union leadership.

Journalist Carol Hunt, meanwhile, feels strongly that the legacy of the lockout has been misappropriated - absorbed into nationalist mythology, ignoring Larkin's focus on international labour rights and his ties to British Labour.

Instead of risking all for the poor and dispossessed workers, the leaders of the lockout are perhaps better known as emblems of Irish nationalism.

Their role as nationalist icons, though, may have helped the union cause. Yeates contends the lockout was the first serious debate about what kind of country Ireland should be.

The employers may have claimed victory, but the concessions that followed and the conscious connection of the labour movement to the Free State by Connolly and his successor William O'Brien, perpetuated the unions.

As Padraig Yeates asks, in how many countries are trade unionists household names?

According to Neil Gibson, economist at the University of Ulster, the history of the unions and the sense of autonomy they engendered are still benefiting the Irish economy.

The Republic of Ireland is seen as the model of rectitude within the EU, instituting public sector pay cuts and tax rises without significant industrial unrest.

The workers have broadly accepted the cuts and in exchange have been able to gain greater job security and improved conditions. An unemployment rate of 13.7% (CSO Ireland) is around half that of fellow Eurozone member Spain (Bloomberg) and compares favourably with Portugal (16.4%).

Connolly's statue, which stands opposite Liberty Hall, headquarters of SIPTU, is flanked by his own words: "The cause of labour is the cause of Ireland...The cause of Ireland is the cause of labour."

Padraig Yeates argues that the Catholic Church became the cause of Ireland but "the lockout was unique, an anomaly. It transcended religion and politics, unlike other disputes, uniting the worker. As the influence of the Church wanes and the economy rebalances after years of excess, perhaps at its centenary, the spirit of the lockout will act as a uniting force one more."