Roger Casement: How did a hero come to be considered a traitor?

- Published

In 1911, Roger Casement knelt before King George V and was knighted for his humanitarian work.

Five years later, he was hanged for treason at London's Pentonville prison and his naked body thrown into an open grave.

The knight who had served the British Empire with distinction had become a fervent Irish nationalist.

Mario Vargas Llosa reflects on Roger Casement's legacy in Ireland

His activity in that cause, during a time of war, was deemed to be treason and a diary that held a dark secret would seal his fate at the gallows. There would be no mercy for the hero who had become a traitor in the eyes of Britain.

A life full of contradictions has inevitably left a legacy just as mixed and is still being debated.

Early years

Casement was born on 1 September, 1864, in Kingstown, County Dublin, to a Protestant father and a Catholic mother.

He was secretly baptised into the Catholic faith by his mother at the age of four. However, Casement thought of himself as a Protestant for most of his life, only formally converting to Catholicism while in prison just weeks before his death.

Casement's mother died in 1873, and his father died in 1877. He went to live with his uncle, John Casement, in Magherintemple near Ballycastle, County Antrim, and was educated at Ballymena Academy.

Humanitarian

After leaving school in 1880, Casement lived briefly in Liverpool before finding employment in administration and civil service work in Africa.

From 1895 he held consular appointments at various locations in Africa, including the Congo, where the British Foreign Office authorised him to report on Belgian mismanagement.

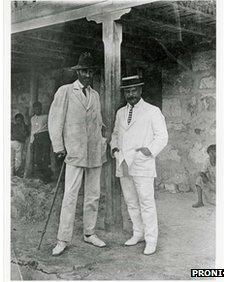

Casement in Peru with boss of the Peruvian Amazon Company

His report condemned the vicious treatment and infringement of human rights of the indigenous people.

Following consular service in Brazil, Casement was commissioned to undertake a report on the alleged abuse of workers in the rubber industry in the Putumayo basin in Peru.

His 1911 Putumayo Report exposed the cruel and exploitative treatment of indigenous people by a Peruvian company and set a precedent for the British Consulate to intervene on behalf of native peoples.

The Putumayo Report had considerable impact, gaining Casement international recognition as a humanitarian. His contribution was acknowledged with a knighthood from the King on his return to Britain.

Nobel laureate

Mario Vargas Llosa, external, a Peruvian author and 2010 Nobel laureate in literature, wrote a novel based on Casement's life, El Sueño del Celta (The Dream of the Celt).

Vargas Llosa believes Casement was a man ahead of his time in exposing the widespread abuse of colonised countries and natives.

"I think Casement is one of the great fighters of human rights of the late 19th, early 20th Century. He was probably one of the first Europeans in denouncing colonialism," Vargas Llosa said in an interview with BBC News in 2011.

"I am fascinated with the courage with which he fought against abuses, injustice and the atrocities that were committed in Africa and in the Amazon basin. He opened the eyes of the world to the reality of colonialism."

Irish nationalism

Disillusioned with colonialism, Casement eventually retired from diplomacy and dedicated himself to the Irish nationalist cause. He was a member of the provisional committee of the Irish Volunteers, external, who launched on 25 November 1913, with the aim of opposing the Ulster Volunteer Force.

So what brought about Casement's apparent dramatic U-turn, from British diplomat decorated by the Crown to Irish nationalist?

Mario Vargas Llosa reflects on Roger Casement's humanitarian work

There is evidence from early letters and poems he had written, that even as a teenager he was interested in the Irish nationalist cause. He had also been a member of the Gaelic League and had been learning Irish.

Anti-imperialism

Author Angus Mitchell, external, who has written several books on Casement, believes he was not strictly anti-British but anti-imperialist.

"As an adolescent Casement identified with Irish rebellious activity," Mitchell said in an interview with BBC News in 2011.

"But his real anti-imperialism actually begins with his work in Africa and particularly in South America, which turned him completely against not merely the British Empire but all empires, and he dedicated his life to trying to overthrow empires on every front."

As World War One broke out Casement felt Ireland should stay out of the conflict, which he saw as an imperial engagement.

Casement on U-boat prior to his arrest in Kerry

Attracted by the potential of an Irish-German alliance as a way of securing full Irish independence, he conceived a plan for an uprising. He attempted to raise an Irish Brigade by recruiting Irish soldiers who had fought for Britain and been captured by Germany.

Casement travelled to Germany, but his recruitment efforts were not successful. When he realised German promises of soldiers and 200,000 rifles were not going to be fulfilled, he believed Irish plans for an uprising would be futile, so he returned to Ireland in an attempt to stop it.

In April 1916, Casement was dropped off in County Kerry by a U-boat and arrested by British authorities. When the Easter Rising began, he found himself in the Tower of London awaiting trial for treason.

Hanged for treason

On 29 June, 1916, Casement was found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death. A campaign for a reprieve was supported by leading political and literary figures, including W B Yeats and George Bernard Shaw.

Casement's diaries had, however, been discovered by this time. Extracts of the 'Black Diaries', as they became known, were widely circulated and revealed that he was homosexual.

Such was the explicit sexual nature of the diaries that the scandal they provoked precluded any possibility of a reprieve and he was stripped of his knighthood.

Casement was executed on 3 August, 1916.

Casement's legacy

Within the unionist community, Casement is remembered primarily for what that community considers to be his treachery.

Sam Wolfenden, head of history at Bangor Grammar, external and a former head boy at Ballymena Academy, Casement's old school, reflects on his legacy in the predominantly unionist town of Ballymena.

"I think he is regarded in Ballymena as a man who betrayed his country. I remember as a student asking why our school had no tribute to Casement. The reply, from a teacher who was a humane and liberal man, was that the school had no intention of erecting monuments to traitors. It was as simple as that," he said.

"His incredible work overseas deserves to be more widely recognised. Perhaps the passage of time will lead to a reassessment of Casement."

Regarded as a traitor in Britain and among unionists, Casement is not universally accepted by nationalists in Ireland either, Angus Mitchell believes. He attributes this partly to Casement's work for the British consular service, but he feels there are other reasons why many are not keen to embrace his legacy.

"The issue around his sexuality is a major reason why Casement remains publicly embarrassing in Ireland. Casement has never really sat comfortably in the pantheon of 1916 leaders, because Ireland has tended to promote its revolutionaries as hyper masculine figures, who have stood up for the nation and nothing else."

But Mitchell says in Congo and Peru there is growing recognition of Casement's humanitarian work. He feels the apparent contradictions in Casement's life are reflected in his mixed legacy:

"The great paradox in Casement's life is that he is both a traitor and a hero. He continues to live in this no man's land of history, claimed by no one."

Mario Vargas Llosa believes that in spite of the controversy of his life, it is time to redress the balance in terms of how Casement is remembered.

"His life was full of contractions and people don't like contradictory heroes, they like perfect heroes," he said.

"Roger Casement was not perfect. I think he was a tragic figure. But he should be regarded as a pioneer in the fight against colonialism, racism and prejudice."

- Published11 March 2011

- Published7 October 2010