NI state papers: Concern over use of plastic bullets

- Published

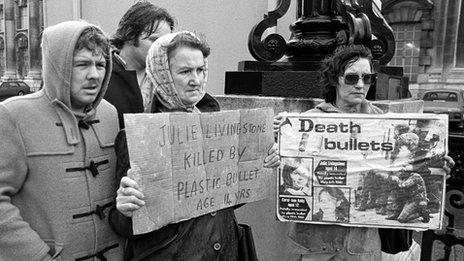

Campaigners protested against the use of plastic bullets in the early 1980s

Research by a number of clinicians at Belfast's Royal Victoria Hospital into injuries caused by plastic bullets concerned the government in 1983, according to this year's releases from the Public Record Office in Belfast.

In 1979 the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) sought to facilitate research into the types of injuries caused by plastic bullets following a request from the military section of the Army. This followed the Army's use of rifled weapons to fire these missiles.

The request caused a flurry of correspondence among Stormont officials. In a letter to NIO officials on 22 May, 1979, Dr D J Sloan, the deputy chief medical officer for Northern Ireland, discussed the best way of collecting data for the military on injuries caused by baton rounds.

While casualties from civil disturbance could go to any hospital in Northern Ireland, he felt that the bulk would probably go to the RVH.

"One could probably get the kind of information suggested from the casualty department at the Royal in an informal way without any 'leakage'. I do not think that this could be done for all NI hospitals," Dr Sloan wrote.

In a note in the file dated 22 May, 1979, P J Dean of Army headquarters in Northern Ireland informed Alan Elliott at the Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS) at Stormont that during 1978-79 a total of 1,927 plastic bullets were fired in Northern Ireland.

Mr Dean added: "The number of hits claimed is small, only a few per cent of rounds fired."

'Killed or injured'

However, the actual number of 'hits' was likely to be much higher than that.

During the violence surrounding the 1981 IRA hunger strike in the Maze prison, a number of children were killed or injured by plastic bullets.

This prompted a consultant neurosurgeon at Booth Hall Children's Hospital in Blackley, Manchester, to write directly to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher on the use of the weapons.

Dr C M Bannister told the prime minister that she had recently visited the RVH and was taken on a tour of the wards.

"It was inevitable that I should see children who have recently been injured by plastic bullets. I am sure you are aware of the extent and severity of the injuries that these missiles are inflicting on the brain of the under-15s," Dr Bannister told Mrs Thatcher.

"Forgive me for repeating a few well-known facts... The brain is unable to rejuvenate itself and any loss of substance leaves a permanent deficit.

"The skull of a child is easily shattered and penetrated by a hard object travelling at speed. A plastic bullet striking the head of the child not only penetrates the skull, driving small fragments of bone into the brain, but it also causes considerable local tissue deformation."

'Greatly distressed'

Dr Bannister added: "Survivors have a high probability of being paralysed down one side of the body as well as intellectual and personality changes. Some will probably be so disabled that it would be better if they had not survived at all."

The visiting surgeon was clearly shocked by the impact of these injuries on relatives and medical staff alike, as she told Mrs Thatcher: "It goes without saying that the relatives of these children are greatly distressed, but it seems to me that the medical and nursing staff were also deeply affected and were extremely depressed by the presence of so many severely injured and pathetically young patients in their wards."

She concluded: "I cannot believe that it is beyond the ingenuity of the security forces to devise a less dangerous means of deterring these youngsters.

"Please persuade them to give this matter the most urgent consideration.

"However much one condemns the actions of these children, one cannot condone the injuries they are receiving."

In a personal reply on 5 June 1984, Mrs Thatcher stated that she shared Dr Bannister's concern at the injuries sustained, particularly since the young victims were "rarely the instigators of the disturbances".

However, Mrs Thatcher went on to defend their use by the security forces in Northern Ireland.

"The use of the baton round is strictly controlled by police and army regulations and incidents where there have been serious injuries or fatalities are thoroughly investigated," she said.

'Minimum force'

In the prime minister's view, the use of baton bounds must be seen in the context of recent events in Northern Ireland.

"It has been used because in the professional judgement of the chief constable and GOC - which I support - it is the most effective means of controlling the recent severe rioting that is consistent with the principle of using a minimum of force," she wrote.

"Police and soldiers have been subject to sustained and ferocious attack."

In a note on the file, J J O McClenahan of the Police Division of the NIO at Stormont House informed the Secretary of State, Jim Prior: "We have not attempted to refute [Miss Bannister's] opinion about the effect of baton rounds."

By this stage the injuries caused by plastic bullets were being highlighted by leading clinicians at the RVH in a series of medical articles.

On 2 July, 1981, at the height of civil disturbances surrounding the ongoing hunger strike, Dr R J Weir, chief medical officer for Northern Ireland, informed officials of the publication of a short article from the neurosurgical unit at the RVH on the head injuries caused by baton rounds.

Dr Weir felt that steps could be taken "to have the publication delayed or some modification made to the non-clinical content".

However, he felt that it would be "irresponsible to withhold information which could mean lives being made or a gross handicap being prevented".

In September 1981, the Belfast-based newspaper, the Irish News, reported that a survey of 100 victims of plastic bullets had been carried out by two Belfast surgeons, Mr William Rutherford and Dr Lawrence Rocke.

This followed the deaths from head injuries caused by plastic bullets of two children, Carol Anne Kelly (12) and Julie Livingstone (14) and Mrs Nora McCabe.

The surgeons concluded that the plastic bullet was a more dangerous weapon than its predecessor, the rubber bullet, particularly to children with their weaker skulls.

"Range for range", said Dr Rocke, "they seem to have a greater wounding potential and result in more deaths".

Dr Éamon Phoenix is a principal lecturer in History at Stranmillis University College, Queen's University, Belfast and a broadcaster and commentator.