IRA Brighton bomb slowed British-Irish peace talks

- Published

The attempt to murder Margaret Thatcher in Brighton nearly led to the collapse of secret Northern Ireland peace talks, according to newly released documents.

The 1984 IRA bombing of the Grand Hotel in Brighton, during the October Conservative Party conference, killed five people and injured 31 others.

Four months earlier, Mrs Thatcher got Cabinet approval for a series of secret meetings with the Irish government.

However, she was reluctant to approve their continuation after the attack.

Private correspondence between Mrs Thatcher and her closest advisers, revealed in the National Archives on Friday, show the prime minister deliberately tried to cool negotiations after the bomb.

She commented that Britain must avoid the impression of "being bombed into making concession to the Republic".

In a handwritten note, Mrs Thatcher told Charles Powell, one of her closest advisers and the government official leading Number 10's involvement in the negotiations: "The bomb has slowed things down and may in the end kill any new initiative, because I suspect it's the first in a series."

The meetings were known within Downing Street as the "Armstrong/Nally talks", named after Sir Robert Armstrong, then British Cabinet secretary, and Dermot Nally, the then secretary to the Irish government.

In June, Mrs Thatcher had told the government: "It was necessary at this juncture to look further ahead into Ireland than the British government had done before.

"Ten thousand British soldiers could not be left in Northern Ireland forever, nor could the very considerable cost of subsidising the province be sustained, without continuing search for possible forward movement."

The covert meetings were launched to find solutions to the Northern Ireland crisis that were agreeable to both countries, and have since been viewed as a crucial steering committee for the Anglo-Irish Agreement announced in November 1985.

The meetings were successful in the months before the attack. By October, Sir Robert Armstrong told Number 10 that he and Mr Nally had found multiple "hypothetical" measures "on which both sides might agree".

In a briefing paper he drafted in the week before the bomb, published for the first time on Friday, he outlined in detail a proposed joint security commission, mixed law courts and raised the idea of an Anglo-Irish parliament.

He wrote in addition: "Both sides agree that it would be desirable to introduce a system of devolved government into Northern Ireland."

Following a meeting days after the bomb, Sir Robert told Number 10 Irish Prime Minister (Taoiseach) Dr Garret Fitzgerald, wanted to agree the basis of the Anglo-Irish Agreement by December - a full year before the announcement was actually made.

However, after the bomb, Mrs Thatcher's adviser, Mr Powell, told the Foreign and Commonwealth Office on October 19 1984: "The prime minister commented that the terrorist bomb in Brighton has slowed these confidential talks down and may, if it turns out to be the first in a series, kill the initiative altogether."

On the same day, Mrs Thatcher added: "The events of Thursday night in Brighton mean that we must go very slowly on these talks if not stop them. It could look as if we were bombed into making concessions to the Republic."

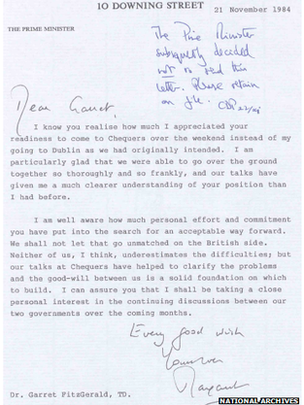

A letter written by Margaret Thatcher to then Irish leader Garret Fitzgerald that was never sent

Her adviser, Mr Powell, subsequently wrote to Sir Robert, directing him on how to negotiate with Mr Nally in an upcoming meeting.

He said: "The prime minister does not at this stage wish you to discuss a possible communique for the Anglo-Irish summit with Irish officials.

"She wishes to reflect further on whether there should be a communique at all. I should be grateful therefore if this item could be dropped altogether from your discussions."

In further communication with advisers in the following week, the prime minister wrote: "I'm very pessimistic. I do NOT think we can take this matter much further."

Several weeks later, Mr Powell wrote of the government's tactics for Mrs Thatcher's upcoming summit with Dr Fitzgerald in London: "The prime minister said there could be no question of the summit taking decisions on the issues raised in the Armstrong/Nally talks."

He added that it would be necessary "to make clear to the Irish that there is no question of substantive decision" on a joint approach to the Northern Ireland crisis.