Irish language policy of Northern Ireland Executive criticised

- Published

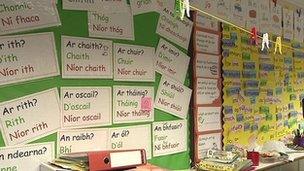

The report said the Irish language is not adequately promoted in schools, government or the media

The Northern Ireland Executive has been strongly criticised over how it promotes the Irish language in a report published by the Council of Europe.

The council is a human rights organisation with 47 member states.

Stormont failed to provide the council with information on the use of both Irish and Ulster-Scots, because the NI parties could not agree a submission.

The council's report said more should be done to promote Irish, including in NI's courts and the assembly.

'Lacking information'

Stormont's power-sharing coalition and other devolved administrations are required to submit information on minority languages to the Council of Europe.

Every three years, the council uses the information provided by various governments to compile a report on the state of minority languages, including Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Cornish and others.

Despite repeated requests from the UK government, the Northern Ireland Executive was unable to reach a consensus on its submission regarding Irish and Ulster-Scots.

As a result, the authors of the Council of Europe report state that their latest publication is "incomplete, lacking information about the situation in Northern Ireland".

They said this had "hampered the process of timely and effective application" of the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages across the UK.

'Long list of grievances'

The report has been rejected by unionist politicians.

Democratic Unionist MEP Diane Dodds said: "The report from the Council of Europe in relation to the Irish language takes a long list of aims, objectives and grievances from Irish language activist groups and places them in list form within the report.

"It is worth noting that the Executive does meet its commitments in law, including the St Andrews Agreement Act.

"The debate around an Irish language act has ended as it is clear that no cross-community support exists for such a proposal but it is clear that the Irish language is funded and supported by the Executive in line with its commitments."

Ulster Unionist Michael McGimpsey said: "The Council of Europe cannot make binding laws and seems oblivious to the fact that the 1998 Belfast Agreement was the settlement regarding minority languages in Northern Ireland and we have fulfilled our obligations under it.

"There are a number of human rights issues within European borders which the Council of Europe should be busying itself with. The position of the Irish language in Northern Ireland is not one of them."

However, Niall Comer, of the Irish language body Conradh na Gaeilge welcomed the report.

"The lack of political consensus on the Irish language, and the 'persisting hostile climate' in the Stormont assembly as noted in the report of The Council of Europe, has long hindered the development of a much-needed Irish Language Act to protect the rights of Irish speakers on this island," he said.

'Highly contentious'

The report also said there was "no political consensus" on the promotion or protection of Irish and Ulster-Scots in Northern Ireland.

It added: "Promotion of the Irish language remains, regrettably, a highly contentious issue in Northern Ireland."

In the absence of the requested information, the Council of Europe carried out its own fact-finding visit to Northern Ireland, gathering information from civil servants and language organisations.

As a result of its own investigations and interviews, the council is highly critical of the failure to promote the use of Irish in a number of areas in public life, including education, government administration and the media.

The report praised the role of the Ulster-Scots Agency

The report's authors suggest that the UK government should consider allowing the Irish language to be used in courts in Northern Ireland.

They said: "The committee of experts still considers the active prohibition of the use of Irish in court as a restriction relating to the use of the language. The UK authorities have not provided any justification for this restriction."

Delays and obstructions

The authors have also criticised how some politicians regard the Irish language, saying that there should be a system of simultaneous translation in the Stormont Assembly.

They found that there had not been enough action to develop more Irish language pre-school places in Northern Ireland, despite a growth in demand, and they criticised a lack of teacher training places for Irish language speakers.

They also found that there have been delays and obstructions over the provision of bilingual street signs and tourist information.

The Council of Europe has now called for the Northern Ireland Executive to introduce a comprehensive Irish language policy.

In respect of Ulster-Scots, the report concludes that its position had improved in Northern Ireland in recent years, due to the role of the Ulster-Scots Agency.

The authors found that the agency "has had a proactive role in developing a strategy for Ulster-Scots, based on firm language planning grounds".

However, it also points to a lack of qualified Ulster-Scots teachers and said that Ulster-Scots is still largely "absent from public life".

The British government signed the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in March 2000 and it came into force in July 2001.

- Published9 January 2014

- Published6 August 2013

- Published30 March 2012

- Published13 December 2011