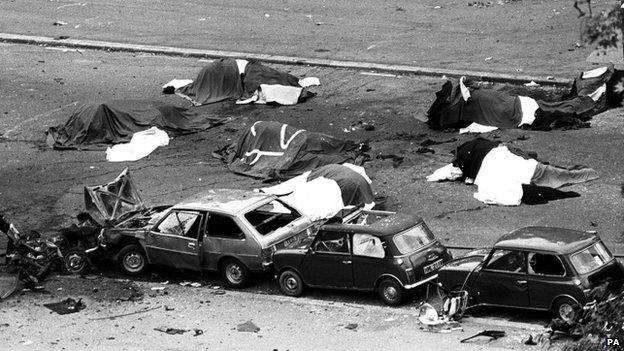

How Hyde Park hearing laid bare John Downey letter blunder

- Published

An Old Bailey hearing, into whether John Downey should be tried for the murder of four soldiers in an IRA attack in Hyde Park in 1982, revealed details of an arrangement to deal with Irish republican 'on the runs'

Mr Justice Sweeney's judgment laid bare the detail of the secret arrangement to deal with on the runs.

It was meant to sort out the anomaly that by July 2000, with the early release of convicted prisoners over, there were several hundred republicans who were still potentially of interest to police.

From the start it was dealt with in an unorthodox way.

Twenty-two IRA men who had broken out of jail were invited to border hotels where they were arrested by appointment and immediately given temporary release papers.

They were then freed on licence under the early release scheme.

John Downey and those like him presented a more difficult challenge. They were suspected of involvement in, but had never been charged with, serious crime.

In May 2000, a process, similar to one operated by the Irish government, that would deal with the so called OTRs was agreed at a meeting between British and Irish officials and Sinn Féin at the Irish embassy in London.

'Serious concern'

Around the same time talks at Hillsborough cracked the IRA decommissioning nut and Tony Blair gave a private assurance to Gerry Adams that the OTR issue would be addressed.

Mr Blair wrote to Mr Adams: "I can confirm that, if you can provide details of a number of cases involving people 'on the run' we will arrange for them to be considered by the attorney general, consulting the director of public prosecutions and the police, as appropriate with a view to giving a response within a month if at all possible."

Work on it began in earnest from this point on.

Senior legal figures were not happy. The then attorney general wrote to Secretary of State Peter Mandelson saying he was "seriously concerned" that the scheme could severely undermine confidence in the criminal justice system.

The process worked like this: Sinn Féin gave names to the NIO. It sent them to the Attorney General for England and Wales who passed them on to the Director of Public Prosecutions in Northern Ireland. He sent them to a team inside the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

Its officers checked their databases to see if the suspects were wanted, and if there was potential evidence linking them to any crimes.

A report was then drawn up for the DPP. He would make a decision about whether there was a realistic chance of prosecution. That was sent to Sinn Féin for delivery to the named individual.

The court transcript shows that, as the process unfolded, the legal establishment was very twitchy about it.

In secret

In 2002 the attorney general for England and Wales wrote to then Secretary of State John Reid saying that it could not become an amnesty and every case would have to be dealt with on the merits of the evidence.

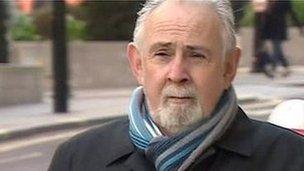

John Downey was wanted by the Met but received a letter assuring that he was not liable to arrest in the UK

He said that he and the DPP(NI) had been careful to ensure that each case was considered on its own merits and was "subjected to the same test for prosecution" as applied in all cases

In 2007, a new team was set up inside the PSNI, only seven strong, which began Operation Rapid. It was designed to review evidence against OTRs wanted for IRA activities before 1998.

The then secretary of state, Peter Hain wanted the scheme to be run in secret. The PSNI prepared a media line should it get into the public domain, but the work was never disclosed.

The press release would say: "As a result of information made available to the Police Service of Northern Ireland, officers from Crime Operations Department are conducting a review of individuals wanted for serious terrorist crime dating back a number of years.

"Inquiries are at an early stage but police are working to determine whether there remains a lawful basis for arrest, having regard to current human rights legislation.

"Where evidence exists, and meets required standards, it remains the role of police to bring those responsible for crime before a court, regardless of their current whereabouts".

John Downey's name was first put forward in 2002. Searches of police databases showed that he was wanted in connection with the Hyde Park attack.

Intelligence linked him to five incidents in Northern Ireland, including the murders of two UDR soldiers in Enniskillen in 1972.

No clarification

Sinn Féin was told he was still a wanted man, and that remained the case up to January 2007.

In May of that year, John Downey's case came before the PSNI officers of Operation Rapid.

Having reviewed the file and the available evidence it was decided he was no longer wanted by the PSNI. The report noted that the Metropolitan Police still wanted him for Hyde Park.

Clarification was to be sought from the Met about that. It does not appear to have been done.

Three days later and on the basis of that report, a senior officer in Operation Rapid told his superior that John Downey was not wanted by the PSNI and that as he was from and lived in Donegal, he was not on the run.

It made no reference to the Metropolitan Police's interest in him.

When asked later why he had not mentioned the Met, that senior officer said he had done his report by the book and the only requirement on him was to establish whether John Downey was wanted by police in Northern Ireland.

Mr Downey was not wanted by the PSNI, he said, and was not considered to be 'on the run' as he was not a resident of Northern Ireland. There was no statutory requirement to supply any further information under the agreed criteria of Operation Rapid.

The NIO subsequently sought confirmation that checks had been done to ensure he was not wanted by an outside force, and this is where it seems the blunder may have happened.

European warrant

It may all have been down to the way the PSNI searched their database. They seemed to have expected that if an outside force had an interest it would be automatically flagged in their system.

But that was not always the case.

If a person with an address in Northern Ireland is wanted by another UK force an entry is listed against their name.

However, if a wanted person lives outside the UK, the formal means of notifying the PSNI would be through a European Arrest Warrant.

John Downey lived in Donegal in the Republic of Ireland.

The judge said: "If checks are not flagging an individual as wanted by a police force in Great Britain or under a European Arrest Warrant then it is correct to report that that individual is not wanted by the PSNI on behalf of either a GB force or a European country."

Was this where John Downey's link to Hyde Park was missed?

It seems that the PSNI thought its search had ticked all the boxes, when in fact it had not.

John Downey got his letter from the NIO, saying he was no longer wanted by the PSNI or any other UK force.

The mistake had been made, but within a year there were several opportunities to rectify it.

The PSNI discovered that John Downey was still wanted by the Met, but did not alert the director of public prosecutions