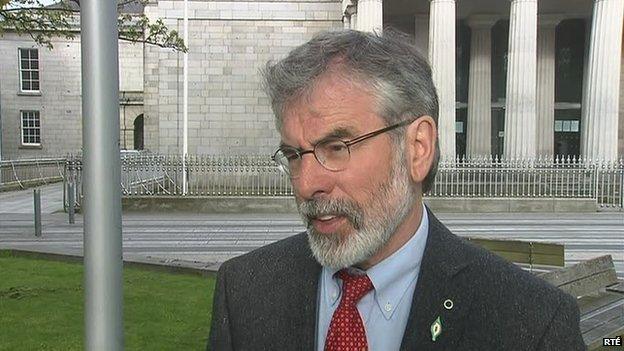

Gerry Adams: Profile of Sinn Féin leader

- Published

Gerry Adams is one of the most recognisable and controversial figures in Irish politics

He is one of the most recognisable and controversial figures in Irish politics.

But, after 34 years as president of Sinn Fein, Gerry Adams has announced his intention to step down as leader.

The move marks a historic shift in the political landscape in both Northern Ireland and the Republic.

The 69-year-old Belfast native emerged from the turbulent history of Northern Ireland to become one the island's foremost figures in republicanism.

To some he is hailed as a peacemaker, for leading the republican movement away from its long, violent campaign towards peaceful and democratic means.

To others, he is a hate figure who publicly justified murders carried out by the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

The paramilitary group is believed to be responsible for about 1,700 deaths during more than 30 years of violence, mostly in Northern Ireland, that became known as the Troubles.

The Sinn Féin leader has consistently denied that he was ever a member of the IRA, but has said he will never "disassociate" himself from the organisation.

Now, following the death of former deputy leader Martin McGuinness earlier this year and Mr Adams' decision to step down, Sinn Féin and the republican movement is facing a new era.

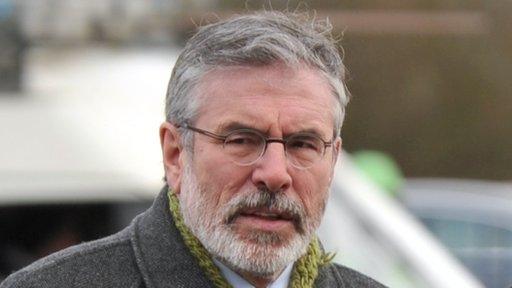

.jpg)

During the Troubles, Gerry Adams was criticised for publicly justifying IRA murders

Gerry Adams was born in October 1948 in Ballymurphy, west Belfast, and both of his parents came from families that had been active in armed republicanism.

His father, Gerry senior, had been shot while taking part in an IRA attack on a police patrol in 1942 and was subsequently imprisoned.

Influenced by his father, the young Adams became an active republican while still a teenager.

He worked as a barman at the Duke of York pub in Belfast where he was fascinated by the political gossip traded among the journalists and lawyers who frequented the bar.

Imprisoned

However, as the civil rights movement gathered pace in the late 1960s, the young Adams did not spend long pulling pints.

Soon he was out on the streets, involved in the protests of the time, and in 1972 he was interned - imprisoned without charge - under the controversial Special Powers Art.

According to his own account, he was purely a political activist, but that same year, the IRA leadership insisted that the then 24-year-old be released from internment to take part in ceasefire talks with the British government.

Gerry Adams pictured with IRA man Brendan Hughes in the Maze prison in 1983

The talks failed and were followed by the Bloody Friday murders, when the IRA detonated at least 20 bombs across Belfast in one day, killing nine people and injuring 130.

Acquitted

Security sources believed Gerry Adams was a senior IRA commander at the time, but interviewed after the organisation's formal apology 30 years on, he adamantly denied this.

In 1977, he was acquitted of IRA membership.

At the height of the 1981 IRA hunger strikes, he played a key role in the Fermanagh by-election in which Bobby Sands became an MP a month before his death.

Two years later Gerry Adams became MP for West Belfast on an absentionist platform, meaning he would represent the constituency but refuse to take his seat in the House of Commons.

Also in 1983, he replaced Ruairí Ó Bradaigh as president of Sinn Féin. Three years later, he dropped Sinn Féin's policy of refusing to sit in the Irish parliament in Dublin.

Despite the tentative moves towards democracy, the IRA's campaign of violence continued and Sinn Féin were considered political pariahs.

Gerry Adams played a key role in leading republicans away from an armed campaign towards democratic republicanism

In the late 1980s, Gerry Adams entered secret peace talks with John Hume, the leader of the Sinn Féin's more moderate political rivals, the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP).

Assassination bids

The Hume Adams negotiations helped to bring Sinn Féin in from the political wilderness and paved the way for the peace process.

But treading a line between politics and violence was risky.

In 1984, Gerry Adams survived a gun attack by loyalist paramilitaries, the Ulster Freedom Fighters, in Belfast city centre. He and three companions were wounded but managed to drive to the Royal Victoria Hospital for treatment.

A second murder attempt was made at Milltown cemetery, west Belfast, in 1988 at a funeral for three IRA members. Three mourners were killed but loyalist paramilitary Michael Stone said his real targets were Adams and Martin McGuinness.

The 1993 Shankill bombing confirmed the tightrope Gerry Adams had to walk in order to keep hardline republicans on board with his political project.

He expressed regret for the bombing that killed nine people and one of the bombers, but did not condemn it.

Mr Adams then carried the coffin of the IRA man Thomas Begley, who died when the bomb exploded prematurely.

Gerry Adams outraged unionists when he carried the coffin of IRA bomber Thomas Begley in 1993

But the Hume-Adams talks were beginning to bear fruit. US President Bill Clinton withstood pressure from London to grant Gerry Adams a 48-hour visa for a peace conference in New York. The visit attracted worldwide attention and Adams used it as justification to press on with politics.

The Hume-Adams process eventually delivered the 1994 IRA ceasefire that ultimately provided the relatively peaceful backdrop against which the Good Friday Agreement was brokered.

In 1998, 90% of the party backed its president in taking seats in the new Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont - a remarkable piece of political management given Sinn Féin's "no return to Stormont" slogan in the 1997 general election campaign.

DUP deal

Mr Adams stayed out of the Stormont power-sharing executive, letting Martin McGuinness take a ministerial post.

When the power-sharing deal collapsed in 2003, Gerry Adams became a key player in the government's attempts to broker a new agreement between Sinn Féin and their one-time enemies, the Democratic Unionist Party.

The negotiations foundered at the end of 2004, but in October 2006 both Mr Adams and DUP leader Mr Paisley indicated their support for the St Andrews Agreement, drawn up after intensive talks in Scotland.

The deal led to a once-unthinkable situation, a Stormont coalition led by the DUP and Sinn Féin.

A key element of the deal was Sinn Féin support for the police, whom the IRA had once deemed "legitimate targets".

All-island strategy

It was unthinkable in the days of the Troubles, but persuading Irish republicans to embrace policing was another step on Adams' personal and political journey between war and peace.

Gerry Adams helped to negotiate the St Andrews Agreement, leading to a once unthinkable political deal involving the DUP and Sinn Féin

In January 2011, Gerry Adams formally resigned as West Belfast MP in order to run for election in the Republic of Ireland.

The move was believed to be in response to fears that the party was too narrowly focused on Northern Ireland and needed to boost its all-island strategy.

The following month, he was elected as a Teachta Dála (member of the Irish Parliament), representing the border constituency of Louth and East Meath.

Sex abuse

However, closer to home, personal turmoil was unfolding in the Adams family.

His brother, Liam Adams, was publicly accused of rape and child sexual abuse. The allegations were made by Liam Adams' adult daughter Aine, who waived her right to anonymity in a bid to bring her father to justice.

Gerry Adams publicly named his own father as a child sex abuser as he spoke about the impact the allegations had made on his whole family.

He then became embroiled in the police investigation, when it emerged his niece had told him she had been abused several years earlier.

The Sinn Féin president said his brother had confessed the abuse to him in 2000 and added that he made his first report to the police about the allegations in 2007, shortly after his party voted to accept the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI).

In 2013, Liam Adams was jailed for 16 years for raping and abusing his daughter over a six-year period.

The following year, Gerry Adams was arrested by detectives investigating the 1972 murder of Belfast woman Jean McConville.

'Innocent'

The widowed mother-of-10 was abducted by the IRA in 1972 and later shot dead and secretly buried on a County Louth beach.

Mr Adams said he was "innocent totally" of any involvement in the killing.

He was questioned for four days, before being released without charge. The PSNI sent a file to the Public Prosecution Service (PPS).

At the time, Sinn Féin accused the PSNI of "political policing" and claimed the arrest was due to a "dark side" within the service, conspiring with enemies of the peace process.

The PSNI said they had a duty to "impartially investigate serious crime" and said they were committed to treating "everyone equally before the law".

Transition

Recent years also saw different sides of Mr Adams, however.

He fully embraced the potential of social media and is well known as an enthusiastic user of Twitter.

He gained a reputation for quirky tweets, many focused on his teddy bear and rubber duck collection.

This frankness has also led him into controversy, however, such as in 2016 when Mr Adams apologised for using the 'N-word' in a tweet comparing the plight of slaves in the United States to that of Irish nationalists.

In the meantime, Mr Adams and Sinn Féin were beginning to make plans for his transition from leadership - and these plans would begin to become public just when Northern Ireland's political process once again hit the rocks.

In January 2017, Martin McGuinness quit as Northern Ireland's deputy first minister in protest at the handling of a botched energy scheme.

Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness are credited with forging Sinn Féin's modern political strength

The move led to an ongoing political crisis that between Northern Ireland's two largest parties, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Féin, that has yet to be resolved.

Soon after his resignation, Mr McGuinness confirmed that he was in ill health and would not be standing for re-election.

The first part of that plan became public later that month when Michelle O'Neill replaced Mr McGuinness as Sinn Féin's leader in Northern Ireland.

New era

Martin McGuinness died two months later, a death that Mr Adams described in his final party conference speech as "a punch in the face".

In September, Mr Adams dropped his biggest hint yet that he was set to step back from politics when he said he would outline the party's "planned process of generational change" if re-elected leader at the party's ard fhéis (party conference).

Now, Mr Adams has confirmed that, after more than three decades, he will no longer be at the forefront of Irish republicanism.

He will step down officially in 2018, when a new leader will be elected, but a long goodbye is not expected.

Sooner rather than later, a new era in Irish politics without Mr Adams will begin.

Family man

Away from politics Mr Adams has been married to his wife Colette for 47 years; she does not have a public profile and does not appear with him at political events.

They have a son, Gearóid Adams, a teacher well known for his involvement in Gaelic football.

Mr Adams is known to enjoy walking, dogs, and Gaelic games, as well as spending time with his grandchildren.

- Published1 May 2014

- Published2 October 2013

- Published26 February 2011

- Published14 November 2010