British government authorised use of torture methods in NI in early 1970s

- Published

The British government authorised the use of torture methods in Northern Ireland in the early 1970s, an RTÉ documentary, external has revealed.

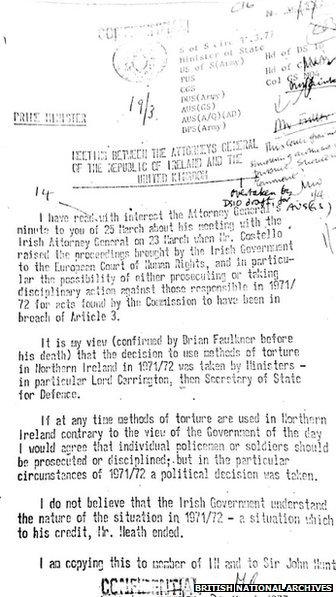

The finding was contained in a memo obtained by RTÉ's Investigation Unit.

The programme alleged the practice was carried out on 14 Catholic men after they were interned, external in 1971.

'The Torture Files' contained correspondence sent by the then Home Secretary Merlyn Rees to the Prime Minister James Callaghan in March 1977.

The memo detailed a meeting between the Attorney General of the Republic of Ireland and his UK counterpart.

'Political decision'

Mr Rees states in the letter that it was his "view (confirmed by Brian Faulkner before his death [NI's prime minister at the time]) that the decision to use methods of torture in Northern Ireland in 1971/72 was taken by ministers - in particular Lord Carrington, then secretary of state for defence."

"If at any time methods of torture are used in Northern Ireland contrary to the view of the government of the day, I would agree that individual policemen or solders should be prosecuted or disciplined; but in the particular circumstances of 1971/72, a political decision was taken," Mr Rees stated in his letter.

"I do not believe that the Irish government understand the nature of the situation in 1971/72 - a situation which, to his credit, Mr Heath (Edward Heath, the then prime minster) ended."

In August 1971, in the wake of escalating violence in Northern Ireland, Brian Faulkner introduced a new law giving the authorities the power to indefinitely detain suspected terrorists without trial (internment).

The law took effect on 9 August and during the next three days, 343 Catholics were arrested.

Twenty-one people died during the three days of unrest - 17 were shot by the British Army, 11 of whom were shot in the Ballymurphy area of west Belfast.

Those arrested were first brought to detention camps in Army bases - within two days more than 100 had been released - the rest were interned.

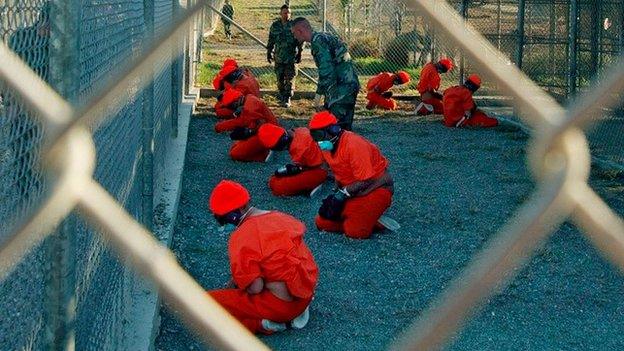

A dozen men were selected, hooded and flown by helicopter to a secret location, believed to be at Ballykelly airbase, County Londonderry.

Two more men later joined the others - they became known as the so-called Hooded Men who had been selected for what the Army termed "deep interrogation".

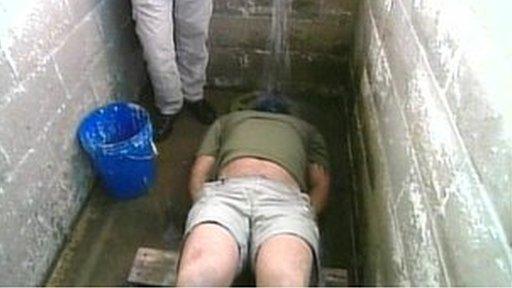

A BBC documentary broadcast in 2012 heard claims that water boarding had been used during the Troubles (reconstruction image)

They claimed they were beaten and subjected to what were called the five techniques, which included food and sleep deprivation and being subjected to very loud noise for long periods.

A BBC Radio Ulster documentary in 2012 also revealed claims the British Army had used a form of torture known as water boarding in NI 40 years ago.

The five techniques the men were subjected to were later banned by the prime minister at the time, Edward Heath.

In December 1971, Ireland lodged a case against the United Kingdom government, alleging it breached the European Convention on Human Rights on torture, discrimination and the right to life.

Degrading treatment

The first stage of the process was an investigation by the European Human Rights Commission following the complaint.

In 1976, it ruled that the British government was guilty of torture and inhumane and degrading treatment.

Ireland, armed with the commission's finding, referred the case upwards to the European Court of Human Rights for judgment.

In 1978, the European court ruled that while the five techniques amounted to inhumane and degrading treatment, they did not constitute torture.

Patrick Corrigan, director of Amnesty International in Northern Ireland, said the revelations in the RTÉ documentary underscored "the need for a comprehensive means of dealing with our troubled past".

He said the 'The Torture Files' had further alleged that the UK government did not disclose relevant evidence to the European Court of Human Rights, in its defence of the case.

"These latest allegations that the UK government misled the European Court of Human Rights in the 'hooded men' case are deeply worrying," he said.

"The revelations underscore the need for a comprehensive means of dealing with our troubled past, and the need for all parties to come clean about their role in human rights violations and abuses."

- Published6 October 2012

- Published21 June 2012

- Published21 June 2012

- Published10 December 2014