IRA ceasefire: Looking for peace through the fog of war

- Published

There were celebrations in republican circles when the ceasefire was announced

A new BBC documentary is to explore the run-up to the IRA and loyalist ceasefires of 1994. Sunday marks the 20th anniversary of the IRA calling a "complete cessation of military operations".

It was Wednesday, 31 August, 1994. In the briefest of telephone contacts, the message I was given was: "Same place as Saturday, 11 o'clock".

This was the signal for the IRA ceasefire announcement, the call I had been expecting and the contact that brought an end to days of anxious pacing and waiting.

In the long build-up, Northern Ireland - or the North - had been walked to its very edge many times.

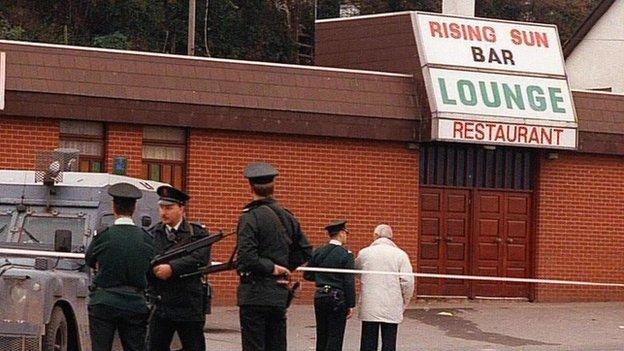

Just months earlier, the news and headlines had been about that bloody week that stretched from the Shankill bomb in Belfast to the Greysteel pub shootings in County Londonderry and the killings in between.

The Rising Sun bar in Greysteel, where eight people were killed in October 1993

So, many had their doubts that a ceasefire was possible.

At Easter 1993, the BBC had controversially used images from an IRA propaganda video - pictures of masked and armed men patrolling in the countryside.

Those pictures were accompanied by sound and a message that included the following: "We call on our enemy to pursue the pathway to peace or resign themselves to the inevitability of war."

And, it was in this fog that many of us struggled to see that something different that SDLP leader John Hume, Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams, former taoiseach Albert Reynolds and influential Irish-American figures were suggesting was possible.

President Clinton and the then prime minister, John Major, were watching developments and, like many of us, waiting to be persuaded.

Perhaps the first real signal was a short 72-hour IRA ceasefire declared at Easter 1994.

But, as the announcement of August 1994 approached, so the loyalist organisations became even more nervous.

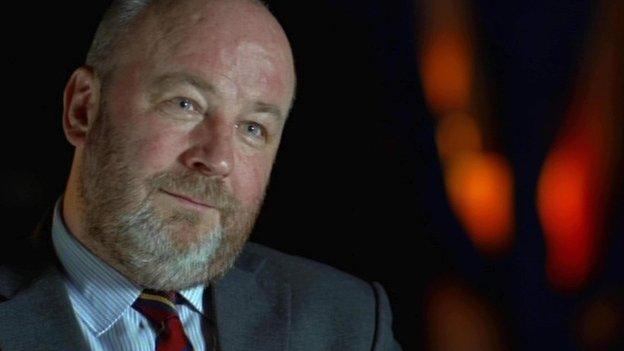

Brian Rowan is a former BBC security editor who has written books about the peace process

The UDA-linked Ulster Freedom Fighters issued a statement on what had become known as the Hume-Adams initiative: "Rather than being in your words an historic opportunity for a settlement of the Ulster conflict, it is a recipe for civil war."

And, on the morning of 31 August, before the IRA statement was dictated to me, I met a representative of the Combined Loyalist Military Command (CLMC).

That command had questions and wanted answers from unionist political leaders and from Downing Street.

"Is our constitution being tampered with or is it not?," they asked.

"What deals have been done?"

And, I had those words noted when, an hour or so later in west Belfast, a woman read the text of the IRA statement to me and my journalist colleague Eamonn Mallie.

In Dublin, other correspondents including the BBC's reporter Shane Harrison and Charlie Bird of RTÉ, were also briefed.

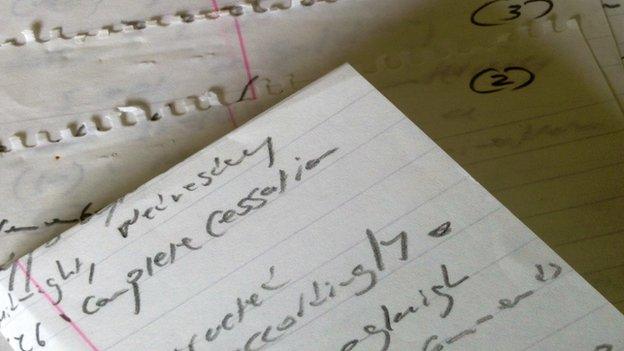

On five pages of a jotter and in pencil, I noted the IRA statement; its headline was the decision to announce "a complete cessation of military operations, external", much more than was anticipated by those in policing and intelligence circles.

Brian Rowan took copious notes about the "complete cessation" of IRA violence

But I remember going back into a BBC studio and hearing the beginning of a political word battle.

The IRA had not described its decision as permanent and the issue of arms decommissioning became a barrier to negotiations.

Sinn Féin and the loyalist parties - after the announcement of a CLMC ceasefire on 13 October - entered exploratory talks with government officials.

But, after 18 months, the ceasefire was lost in the bomb and the bodies of the London Docklands attack in February 1996.

And what have we learned from those decisions and declarations two decades ago?

It is that conflicts don't end in an instant.

Peace-building is a process; protracted, painstaking, plodding and, at times, infuriatingly pedantic.

It works and doesn't work - it makes progress and then goes backwards or jogs on the spot.

And, 20 years from now, people will still be examining and debating the significance of that August day in 1994.

It was a first step out of a war mindset, a big step that prompted and encouraged other steps.

And, we now know, that it was beginning and not an end.

Brian Rowan is a former BBC security editor and an author on the peace process. He is interviewed for the Monday night's BBC One documentary Ceasefire that will be screened on Monday 1 September at 21:00 BST

- Published22 November 2013