Remembering the IRA ceasefire 20 years on

- Published

- comments

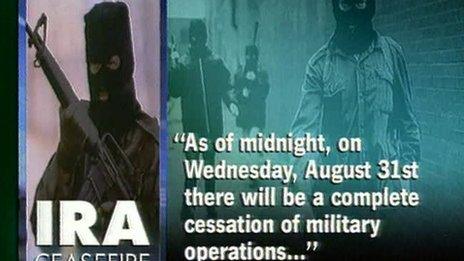

The statement as it appeared on BBC NI's Newsline

Listening back to my breathless tones when I announced the 1994 IRA Ceasefire on BBC Radio 5 Live, external I can forgive one radio newspaper reviewer who accused me of getting over-excited.

In fact it wasn't excitement which had taken my breath away, but a brisk 100-yard dash between the phone where my colleagues Brian Rowan and Shane Harrison were ringing in their ceasefire statements and the radio studio where Diana Madill was awaiting my on-air interruption.

My immediate analysis concentrated on whether a "total" cessation amounted to a "permanent" ceasefire. Since the 1970s, the only recent ceasefires Northern Ireland had experienced were short three-day Christmas truces.

So it's understandable that commentators and politicians remained unsure whether the 1994 initiative would last.

Lives saved

Of course the ceasefire did break down, with the IRA Docklands bombing in 1996. But, taken together with the October 1994 loyalist ceasefire, it pointed the way forward. Its restoration in 1997 provided the momentum for the eventual deal in 1998.

The peace ushered in by the ceasefires has been far from perfect, with the emergence of dangerous dissident republican groups, sporadic violence involving some loyalist factions and continuing tensions on the streets over parades and flags.

However there's no doubt that hundreds of lives have been saved, and that's something which shouldn't be forgotten whenever we debate the drawbacks of the system of government which emerged from the lengthy post-ceasefire negotiations.

Stormont's arch critic, TUV leader Jim Allister, describes the ceasefire as "the carefully choreographed outworking of secret and nefarious negotiations between murderers and the government of those they murdered." For Mr Allister 31 August 1994 marks "the sordid genesis of the failing Stormont arrangements."

By contrast, Gerry Adams reckons the IRA move was "historic and ground breaking". The Sinn Fein president says London, Dublin and Washington must return to the "same level of engagement" they demonstrated in the mid-1990s in order to defend the political institutions against "their most serious challenge for many years."

New priorities

We are in a changed world. When we hear about truces and ceasefires, our thoughts turn to Gaza or Ukraine rather than closer to home. The funding of Northern Ireland's health service is currently top of the local news agenda - back in 1994 our hospitals weren't being kicked around between competing ministers, instead they were overseen by Baroness Denton, a Conservative peer from Yorkshire, who also had to look after the local agriculture sector.

What hasn't changed is the ability of our politicians to negotiate any issue right up to a deadline and then beyond. The talks that went on before and after the ceasefires have left a lasting mark on our political culture.

The institutions created in 1998 - with their built in guarantees and vetoes - encourage a propensity towards delay and stalemate. Stormont has enjoyed a rare period of stability but as the parties accuse each other of bad faith that stability can't be taken for granted.

We have exchanged the tragedy of the "Long War" for the uncertainty of a continuing long political game.

- Published28 August 2014

- Published27 August 2014