George Hackney: Unseen WW1 photos uncovered

- Published

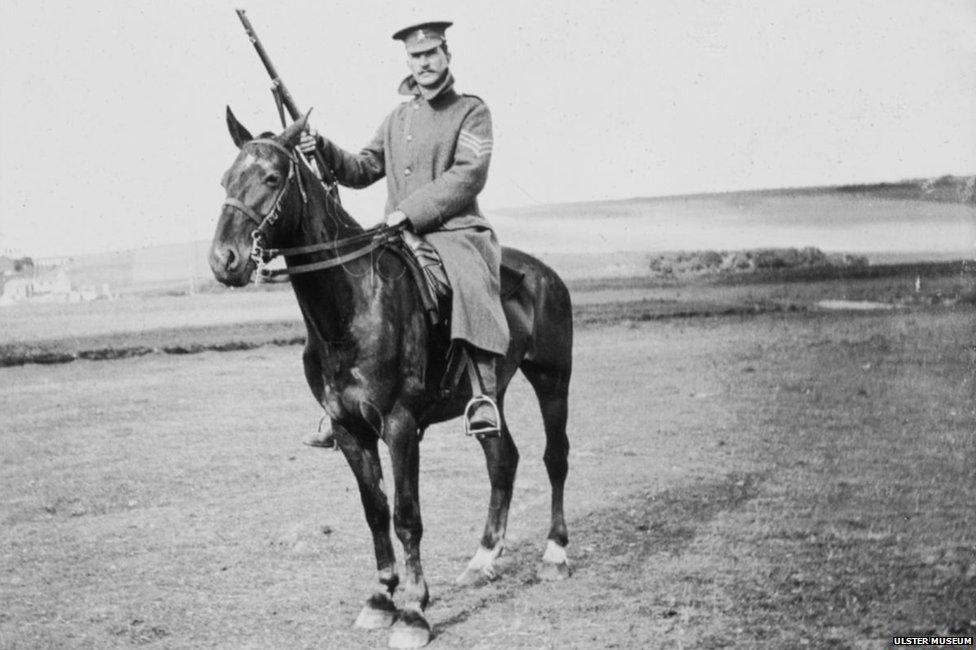

Sgt James Scott, photographed at Seaford, East Sussex at some point between July and October 1915

A startling collection of previously unseen photographs featured in a new documentary provides a fresh perspective of life and death in the trenches during World War One

Belfast man George Hackney was a keen amateur photographer in the innocent years before the outbreak of war, and when he was sent off to fight in 1915, he took his camera with him.

Unofficial photography was strictly illegal, but this means his snaps have a candid quality that capture the often mundane aspects of life in the trenches, as well as an almost unbearable sense of poignancy as many of these men never made it home.

Hackney himself lived into his late 80s, and his collection was donated to the Ulster Museum before his death in 1977.

However, the photographs sat in the archives unseen by the public, until a curator showed them to a filmmaker.

Two years later, a documentary to be broadcast on BBC One Northern Ireland on Monday - The Man Who Shot the Great War - brings the remarkable story of George Hackney and his photography to life.

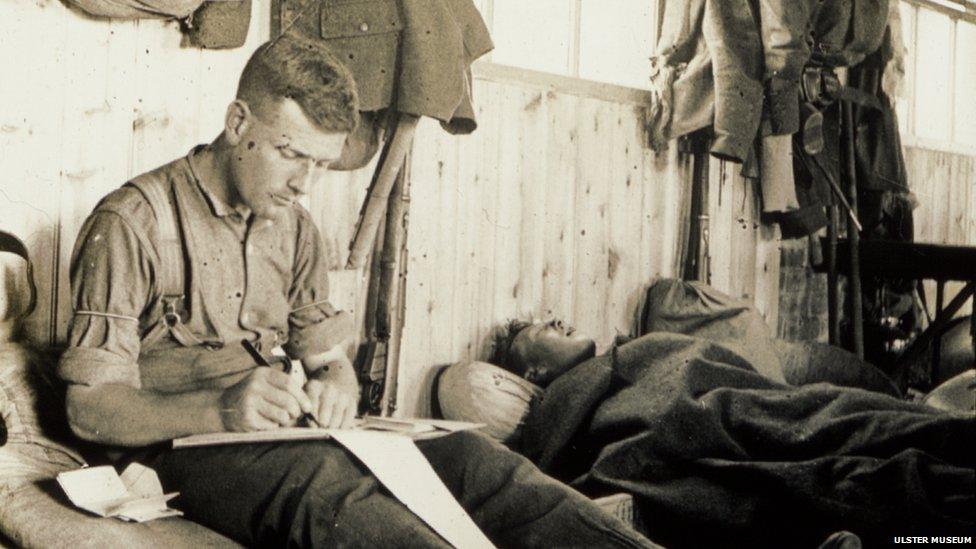

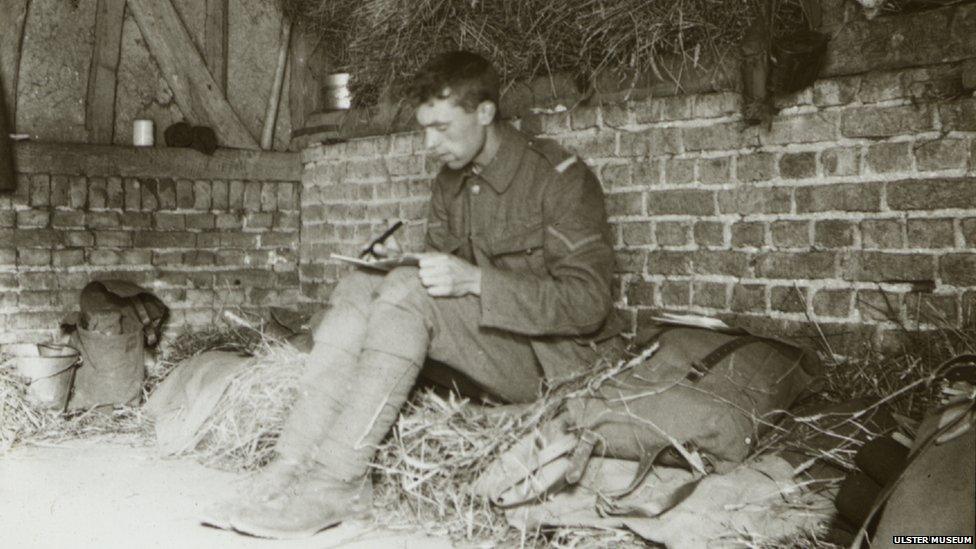

Photograph taken at Randalstown Camp, County Antrim 1915. Hackney's friend John Ewing from Belfast writes in a diary or a letter home, while his comrade lies sleeping in his bunk. Ewing was later promoted to sergeant and won the Military Medal for bravery in the field

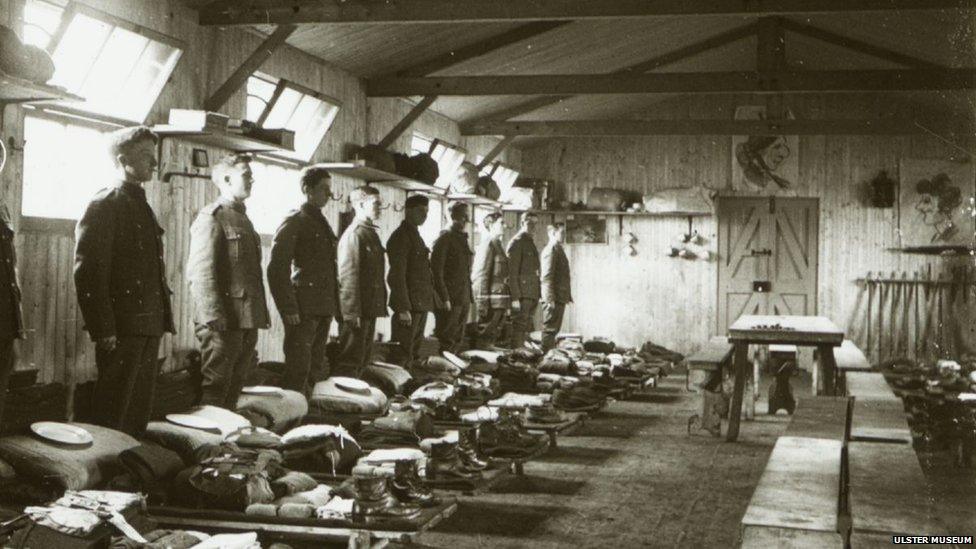

Photograph taken at Randalstown Camp, County Antrim 1915. The 14th Battalion Royal Irish Rifles moved to Randalstown from Finner Camp in January 1915, where they remained until moving to England in July. In Randalstown, they stayed in wooden huts, and Hackney photographed the interior and exterior of these huts

Its director, Brian Henry Martin, says a series of lucky coincidences helped to unlock the secrets of this treasure trove of insight into life and death on the Western Front.

"I was first introduced to these photos in the Ulster Museum's archive by Dr Vivienne Pollock in 2012 while working on a documentary about the Ulster Covenant, and it immediately raised so many questions," he says.

"Unofficial photography was banned on the Western Front, so who took these photos, how did they manage it and why have we not seen them?"

His research led him to the Royal Ulster Rifles Museum in Belfast city centre, where he hoped the 36th (Ulster) Division's war diary could provide some vital clues about where and when the photographs were taken.

Brian Henry Martin describes the work of WW1 photographer, George Hackney.

"When I got there, someone else was looking at the diary so we ended up jostling over it and passing it back and forth - we ended up chatting and it turns out that the guy was Mark Scott, whose great-grandfather was Hackney's sergeant," he says.

Photograph taken English Channel, 4 October 1915. The Battalion sailed from Southampton to Boulogne on the former Isle of Man paddle steamer Empress Queen. Some men are seen sleeping on the deck while others look overboard for the threat of German U-boats.

A photograph of George Hackney, taken at Poulainville, Picardy, Northern France, October 1915. Hackney was made a Lance Corporal the day before the Battalion left for France, along with his friend John Ewing. Before advancing to the Front, the men were billeted in a barn in the village of Poulainville.

Three of the photographs were of Sgt James Scott, who was killed at the Battle of Messines in Belgian West Flanders in May 1917, and they had been held by the Scott family.

"He must have given the photos to Sgt Scott's widow, and that opened up a window in that we realised that what Hackney was doing was giving the photos to the families of the men he'd photographed, many of whom didn't come back," he says.

Mr Martin says that as a documentary maker, his chance meeting with Mark Scott turned out to be especially fortunate.

"In making the film, we were looking to speak to a relative who is emotionally involved in the story, someone who knows about World War One and someone who can tell us about photography, and Mark could do all three," he says.

Wartime photographers faced strict restrictions, and it may seem surprising that Hackney managed to bring his camera to the front without being detected.

However, Mr Martin says the camera he used was quite small and "could be folded up to be not much bigger than a smartphone".

"Technology had really taken off in that era, and as an amateur photographer George was at the cusp of that, spending the years before the war honing their skills," he says.

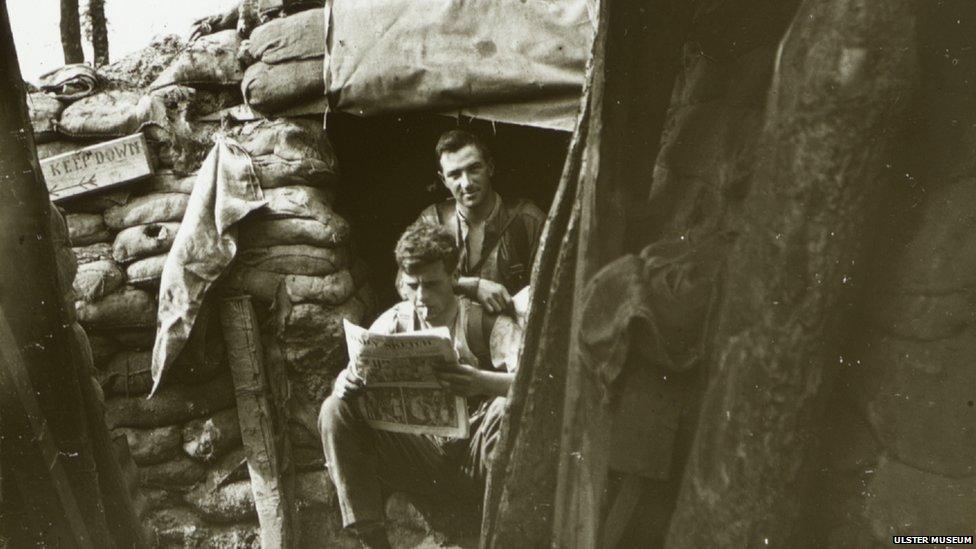

Photograph taken in July/August 1916 at Ploegsteert Wood near Messines in Belgium. This is where the 14th Batallion were redeployed after the devastation of the Battle of the Somme

Mark Scott comments on the rare photograph of scouts/snipers taken in France during the winter of 1915/16: "One photograph in particular George Hackney has described as a sentry post at Hamel - when we look at it more closely there are one or two important points we can pick out of it. There is a rifle to the left of the frame and there is a modified cheek rest attached to the butt of the rifle. This would have been used to help the shooter align his eye to a telescopic sight"

Photograph taken during the Battle of the Somme: One of three photographs taken by George Hackney during the advance of the 36th Ulster Division on 1 July 1916. In the foreground we can see German soldiers surrendering as the 36th Ulster Division advanced upon German lines

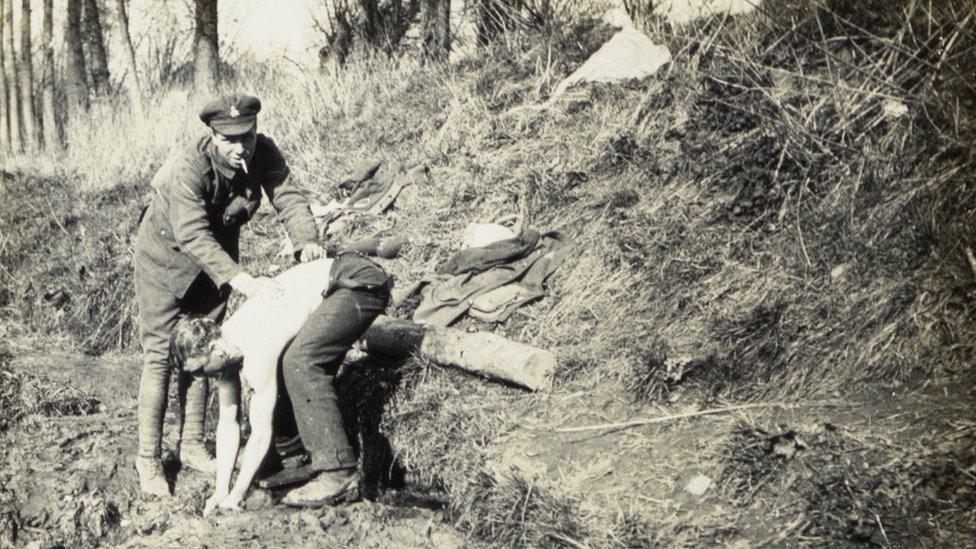

Photograph taken at Thiepval Wood May/June 1916. Paul Pollock, standing and smoking, was the son of the Presbyterian Minister at St Enoch's Church in Belfast, where George Hackney worshipped. He was killed on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. His body was never found and name was only added to the Thievpal Memorial to the Missing in 2013

His ingenuity paid off in grand style, even though it has taken nearly a century for his achievement to be fully recognised.

The programme quotes Franky Bostyn of the Belgian Ministry Of Defence as saying: "I think you made the photographical World War One discovery of the century."

As well as the documentary, Hackney's photographs will form the basis of an upcoming Ulster Museum exhibition.

Mr Martin believes his significance will only continue to grow in stature.

"We eventually tracked down about 300 photographs, but there's maybe 200 more out there," he says.

"I think in a way, the George Hackney story is only beginning and he will become the definitive photographer of World War One in Ireland."

The Man who Shot the Great War is broadcast on BBC One Northern Ireland on Monday 17 November at 21:00 GMT.

- Published27 May 2014