PM's extra cash offer comes out of Stormont's existing coffers

- Published

- comments

First Minister Peter Robinson said if you are going to bribe someone then it's best not to bribe them with their own money

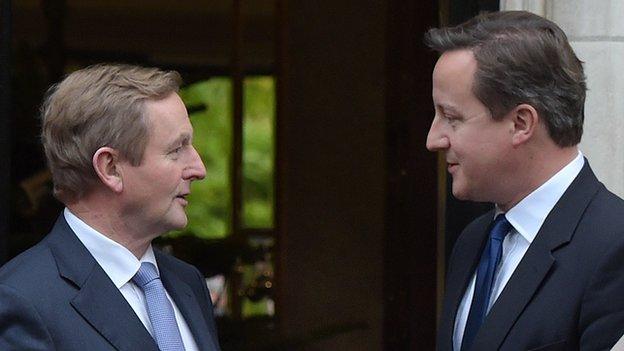

Its principal detractor, the TUV leader Jim Allister, described the prime minister and taoiseach's arrival at the Stormont talks as the "chequebook summit".

Logical, given the amount of chatter in the run-up to the negotiations about peace bonds or a peace investment fund worth hundreds of millions of pounds.

In the event it turned out to be a chequebook which was all stubs and no cheques.

The £1bn in spending power offered by the prime minister is largely a borrowing facility which the executive can already dip into.

True, the Reform and Reinvestment Initiative has so far been limited to new capital projects, so allowing Stormont to use it to fund public sector redundancies (estimated at around £40,000 per worker) is a handy flexibility.

However, as the First Minister Peter Robinson put it, if you are going to bribe someone then it's best not to bribe them with their own money.

The talks may rumble on between now and Christmas, but it's hard to see the basis for a financial deal.

The hope had been that a peace fund, predicated on Northern Ireland's special status as an area emerging from conflict, would have been so generous that it would have provided Sinn Féin with the necessary cover to shift ground on their outright opposition to welfare reform.

But, in the absence of an agreement, why should Sinn Féin do a u-turn on welfare reform?

And in the absence of such a u-turn, why should the UK government authorise Theresa Villiers to sign a cheque her boss wasn't prepared to wave in front of the Stormont House delegations?

Any progress the politicians might make on the details of the Haass issues (flags, parades and the past) look like they will be held hostage to the failure to secure an overall financial deal.

Precarious state

Apart from the supposed Christmas deadline, Stormont observers will now start ruminating on the ability of the executive to agree a final budget for 2015/16 or the possibility that the DUP might bring a welfare reform bill to the assembly only for Sinn Féin to vote it down (a move which would at least clear welfare off the DUP's decks before the Westminster campaign begins).

After that the focus could turn to whether the executive collapses or staggers on in a financially precarious state or whether there's an early election in May in tandem with the Westminster contest.

After the May election, the DUP may have extra cards to play if it occupies an influential position in a future hung parliament.

Sinn Féin won't take their seats in that hung parliament.

Amateurish negotiation

But their attitude remains vital to whether Stormont stays afloat.

According to one unionist source, Gerry Adams told David Cameron face-to-face what he repeated in a tweet, namely that this had been an amateurish negotiation.

The source claims the prime minister retorted bluntly by wondering how the Sinn Féin president knew this as he had only joined the talks for the first time after they had already clocked up 85 hours.

If this account is true, then it points to a radically changed relationship between Sinn Féin and Downing Street.

Either way, Sinn Féin may be wondering if - after a chequebook summit without a cheque - it might be worth waiting to see if the new year brings a new prime minister who might take a different attitude from Mr Cameron, who they have openly described as a "penny pinching accountant".

- Published12 December 2014

- Published12 December 2014

- Published12 December 2014

- Published12 December 2014