Why is Irish language divisive issue in Northern Ireland?

- Published

Gregory Campbell made reference at the DUP conference to his 'curry my yoghurt' remarks

There has been renewed political focus on the Irish language and its use in the Stormont assembly following controversial "curry my yoghurt" comments by the DUP's Gregory Campbell.

There have been calls to protect the language in legislation.

But why is the Irish language such a divisive issue between the largest power-sharing partners and the latest touchstone in Northern Ireland's culture war?

This year's nursery class at Beann Mhadagáin primary school in west Belfast contains some of the 5,000 or so children in Northern Ireland now educated entirely in Irish.

But in another part of Belfast, evening classes are under way. Not far from Stormont, locals are learning Irish in east Belfast.

An upsurge in numbers of Protestants learning Irish would not be surprising to students of history.

At the turn of the last century, Irish, although in decline, was seen as a language for all.

'Markers of identity'

UUP councillor Chris McGimpsey, who has studied Protestant engagement with the Irish language, says: "An integral part of unionist identity in Ireland was the fact that they were Irish.

"There was a great sympathy for and complete comfort with the whole concept of Irish, Irishness and the Irish language."

He says the partitioning of Ireland in 1921 was a turning point in unionist attitudes to the language

The Irish language centre in east Belfast is named Turas, which means journey

Partition prompted nationalists in Northern Ireland to embrace the language in greater numbers, according to the historian Diarmaid Ferriter.

"They felt completely abandoned by their southern counterparts, and in that sense there was more at stake for them when it came to the language," he says.

"There was more importance attached to it because of their minority status and they really needed to find markers of identity."

The survival of the Irish language in west Belfast owes a lot to a pioneering project in the 1960s when a group of families decided to make the Shaw's Road area into a Gaeltacht, an Irish speaking area.

A second wave of Northern Ireland's lrish language revival movement occurred on another site - the Maze Prison.

'Jailtacht'

Republican prisoners and those interned in the Troubles in the early 1970s built on the example of the Shaw's Road Gaeltacht and began learning Irish.

As the campaign for political prisoner status escalated in the 1980s, learning the Irish language - in what became known colloquially as the Jailtacht - became a way for prisoners to set themselves apart from the prison officers.

The Maze Prison became known colloquially as the Jailtacht because of the Irish language's popularity

Feargal MacIonnrachtaigh, whose father was interned in 1973, says republican prisoners would use the language as a means of both communication and resistance.

"People were inspired by this idea that you could reclaim your identity and you could go through a process of 'reconquest' in terms of the language," he says.

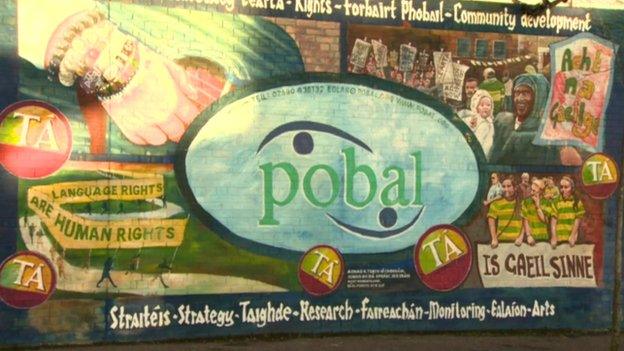

In 1982, Sinn Féin established a cultural department to promote the Irish language.

Mr McGimpsey says that from that point, Sinn Féin was perceived to have "hijacked" the language for political gain.

Manchán Magan is the great grandnephew of Mícheál Seosamh Ó Rathaille, known as 'The O'Rahilly', who fought and died in the 1916 Easter Rising.

"For my granny, the language was a cultural nugget but it was also this weapon of war against the British" he says.

'Almost a weapon'

Despite his republican heritage, Mr Magan says he feels that the language has been "used as a political weapon".

"Sinn Fein started to use it, not just to create pride and identity and a sense of an 'esprit de corps' in their people, but as almost a weapon or a signifier of difference from the unionist community and that was a tragedy," he says.

Linda Ervine runs Irish language classes in east Belfast

Robin Stewart is a former loyalist paramilitary who is learning the language in east Belfast.

"Learning Irish isn't going to make me a republican - in fact what it does is strengthen my own identity and lets me challenge republicans and their version of what Gaelic and Irish history is," he says.

The classes he attends are run by Linda Ervine, a sister-in-law of the late Progressive Unionist Party leader, David Ervine.

'Nothing to fear'

"David learned Irish when he was in Long Kesh along with other loyalist prisoners - he was very proud of the fact that he had a bit of Irish, Gusty Spence was the same.

"They didn't feel threatened by the language; they knew that there was nothing to fear from the language."

The DUP's Gregory Campbell remains unapologetic about remarks he made last month about the use of the language in the assembly by some Sinn Féin MLAs.

"I am offended each time, every single day that they abuse the Irish language," he says.

"Now that means that I will use whatever device I have to use to expose their duplicity, and their politicising of the Irish language."

Sinn Fein MLA Máirtín Ó Muilleoir, who is a prominent Irish language advocate, says: "It is deeply saddening that we have somebody who wants to use the Irish language as a stick with which to beat people.

"No-one has anything to fear from an Irish language, and you know, increasingly when I am out on the streets, I believe that it has been accepted by ordinary people, it has to be a shared language."

'Lessons'

An Irish language act, aimed at helping to support and protect the language, could create an entitlement to use Irish in interactions with government bodies and a number of other services.

However, the actual proposals are not yet available and the minister responsible, Sinn Féin's Carál Ní Chúilín, told Spotlight that she would bring an Irish language bill before the assembly in the New Year.

The issue is also one of the outstanding matters in the current round of talks.

Despite a crusade to establish the Irish language in everyday usage by dominant political figure Éamon de Valera, the Republic of Ireland's last census found that little over 100,000 people speak it on a daily basis.

"I think one of the lessons to be learned from the experience in southern Ireland is if it becomes associated with a particular political project, or if it becomes identified with a particular political impulse, you are not going to succeed in what your professed aim is, which is to promote the speaking of the Irish language" says Prof Ferriter.

In Northern Ireland less than 4% of the population is fluent, although over 10% say they have some ability in Irish

There are some signs of a cross-community revival.

"It would be nice to have a Gaeltacht Quarter in east Belfast, but it would also be nice to have all our cultures understood and recognised," says Mr Stewart.

In Northern Ireland, cultural symbols are an important part of identity and language is often used to imply what cannot be said.

A flags and culture and identity commission is one proposal under consideration as part of the current round of talks, but Stormont has yet to decide on the Irish question.

Spotlight is available to watch on the BBC's iPlayer

- Published2 December 2014

- Published24 November 2014

- Published10 November 2014

- Published3 November 2014

- Published12 April 2014

- Published9 January 2014

- Published25 September 2012