Northern Ireland public sector strike disrupts public services

- Published

Public sector staff across Northern Ireland are on strike, as Mark Simpson reports

The biggest public sector strike in years "brought much of Northern Ireland to a standstill", a union has claimed.

The strike affected education, public transport and administration.

It was taken in protest against public service cuts and Stormont's budget.

Jackie Pollock of Unite said the "scale of today's response took us by surprise, as did the overwhelming support shown by members of the public".

Protesters who called themselves "grassroot socialists" caused traffic disruption in the Millfield area of Belfast during Friday morning's rush hour

The strike caused disruption across many areas.

Health trusts said 1,900 out-patient appointments and 200 in-patient and day case procedures had been postponed.

The Department of Health said arrangements had been put in place to ensure "critical services" would be maintained.

It is understood that most nurses did not take part in the strike.

One patient at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast told the BBC: "We've been told we're not going to get any hot meals.

"Patients are uncomfortable, they're looking for food and wanting to know what's going on - at lunchtime, we got a tiny cup of soup and we were told that's all they could give us because of the strike."

The Belfast Health Trust said there was a more limited choice of food, and if patients were unhappy with what they were offered, "they should speak to a member of staff who will try to arrange an alternative".

An estimated 60% of accident and emergency crews and 80% of rapid response paramedics had planned to strike, but a major incident declared by the Ambulance Service "to maintain a safe level of cover" on Thursday night meant staff were required turn up for duty.

Public transport company Translink did not operate any scheduled bus or train services, except the Ulsterbus express Belfast to Dublin service at 23:00 GMT.

Analysis: John Campbell, BBC News NI Economics & Business Editor

Why are the unions on strike?

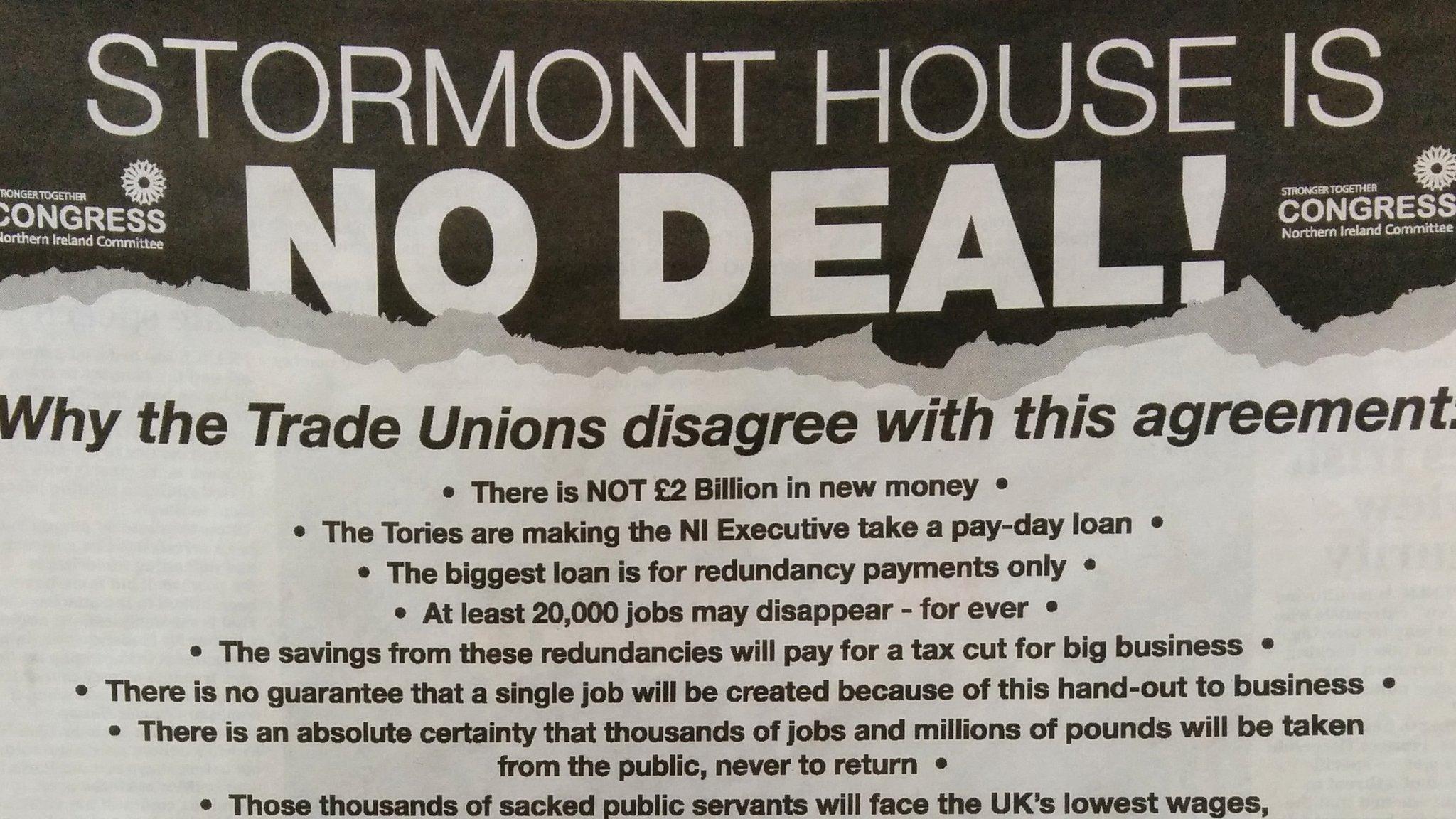

The unions have put the Stormont House Agreement and the budget which followed it at the heart of this industrial action.

They believe Stormont House was a bad deal: bad for public services, bad for their members and ideologically right wing.

They say that cutting 20,000 posts from the public sector will hit services and put workers under pressure.

They also dislike the plan to sell publicly owned assets and are deeply sceptical about what was agreed on welfare reform and the devolution of corporation tax.

The veteran socialist campaigner Eamonn McCann points out that this is the first time trade unions have opposed a Stormont deal.

Sinn Féin and the SDLP are supporting the strike but some politicians might be inclined to ask the unions how they think a better deal could have been achieved.

Thousands of school children were affected by the strike, particularly in the Catholic primary sector as members of the Irish National Teachers' Organisation, which represents mainly Catholic teachers were out on strike.

It was the only teaching union that voted for strike action. The Department of Education said it was the responsibility of school principals to decide if their school would remain open.

Some schools remained partially open due to the strikes

In the controlled sector, most primary schools opened but some closed early because non-teaching staff such as canteen workers and supervisors are on strike. Some schools told pupils to bring packed lunches instead.

While some post-primary schools closed because of the shortage of staff and pupil transport, it appeared that the majority remained open, particularly for exam classes.

The Northern Ireland Committee of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions organised a series of rallies and events to mark what it said was "the largest single day of industrial action in several years".

Translink staff picketed outside the bus depot on the Falls Road in Belfast

Rallies took place in Belfast, Londonderry, Newry, Strabane, Omagh, Enniskillen, Coleraine, Magherafelt, Cookstown, Dungannon and Craigavon.

In Derry, trade unionist Liam Gallagher described the cutting of 20,000 public sector jobs while "claiming it won't have an impact on society" as the "economics of madhouse".

"The rich will be rewarded with corporation tax, while workers will suffer," he said.

The strike comes as efforts continue to resolve Stormont's welfare reform crisis.

Earlier this week, Sinn Féin withdrew support for the welfare reform bill.

Northern Ireland Secretary Theresa Villiers has warned that without agreement on welfare, a budget at Stormont was unsustainable.

The first and deputy first ministers, Peter Robinson and Martin McGuinness, said on Friday afternoon that they have been "making progress" in talks on resolving the impasse.

- Published13 March 2015

- Published12 March 2015

- Published15 January 2015