Electoral pacts: Tough decisions for politicians

- Published

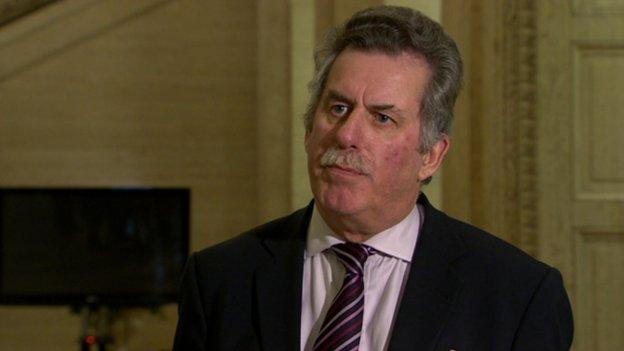

DUP leader Peter Robinson and UUP leader Mike Nesbitt have struck a deal to support single unionist candidates in four Westminster constituencies

We have had stories before about unionists poring over constituency maps and dividing up Northern Ireland.

But, generally, these discussions ended in recriminations with each side accusing the other of letting the unionist voters down.

Vox pops on the street in unionist areas tend to find the concept of unionist unity relatively popular.

But where to fight and where to stand aside is a tough decision for politicians.

They are aware that a decision in one election might set a precedent for another.

In 2010, the Ulster Unionists passed up on the prospect of a grand unionist arrangement in favour of an arrangement with the Conservatives.

Far from yielding results, the ill-fated Ulster Conservative and Unionist New Force alienated North Down MP Lady Sylvia Hermon and ended up reducing the UUP presence in the Commons from one to zero.

Now the unionists have agreed a four-constituency deal that should make the DUP deputy leader Nigel Dodds more comfortable in North Belfast.

It will also enhance the DUP candidate Gavin Robinson's chances of taking back East Belfast from Alliance - a goal especially dear to the heart of DUP leader Peter Robinson who lost the seat.

The sitting MP, Naomi Long, complains that East Belfast is no longer a "fair fight". The DUP retorts that Alliance previously stood aside for the pro-Good Friday Agreement unionist Lady Hermon in North Down.

Ms Long cannot deny that, but says her party has learned its lesson and will not repeat the exercise.

Whilst the benefits of the deal to the DUP are clear, the Ulster Unionists have not reaped the same obvious dividends.

Sinn Féin MP Michelle Gildernew held on to her Fermanagh and South Tyrone seat in 2010 by a margin of four votes

In Fermanagh South Tyrone, Sinn Féin's Michelle Gildernew enjoyed a four-vote margin over the unionist unity candidate in 2010, a result which narrowed further to just one vote after a special election court examined disputed Fermanagh ballot papers.

That means former Ulster Unionist leader Tom Elliot is in with a real chance of taking the seat. But it should be remembered that a pact on one side of the Northern Ireland equation tends to prompt an equally energetic "heave" towards the lead candidate on the other. So expect a very high turnout.

The inclusion of Newry and Armagh in the four-seat deal is puzzling. South Belfast would have been a much better target for the Ulster Unionists.

SDLP leader Alasdair McDonnell may breathe a sigh of relief that he is not facing a single unionist candidate, even though the entry of Sinn Féin's Máirtín Ó Muilleoir into the race still makes the outcome in South Belfast hard to call.

The SDLP has rejected Sinn Féin suggestions they should agree a tit-for-tat pact to counter the unionists. This stance could cost the SDLP in South Belfast. However, SDLP MPs take their Westminster seats, while Sinn Féin do not. That alone would make a pan-nationalist deal hard to rationalise.

Arguments over whether the pacts are anti-democratic or sectarian will no doubt continue as the formal campaign gets underway.

Those in favour insist that, with the polls predicting a hung parliament, maximising Northern Ireland's influence at Westminster makes common sense.

Once the election is over, the immediate focus will no doubt turn to the arithmetic at Westminster, rather than the polling numbers in individual local seats.

However, in the long term, the pacts of 2015 may prompt discussion over future trends in Northern Ireland's politics.

Will the pacts be seen as a step towards eventual unionist unity, or will next year's Assembly elections restore the status quo?

- Published18 March 2015

- Published18 March 2015

- Published21 February 2015