The Great Famine: Donegal Choctaw keeps Ireland link alive

- Published

Native American Waylon Gary White Deer has made Ireland his home

When Native American Choctaw tribesman Waylon Gary White Deer came to Ireland for the first time, he described it as being like "an arrow shot through time".

"There is a teaching among the Choctaw that says feeding someone is the greatest thing you can do because you are extending human life," said the author and artist, who now lives in Donegal.

"The first thing Choctaw people do when a visitor comes to their home is offer them something to eat, or just fix them a plate."

In 1847, it was this generosity that prompted the Choctaw to donate £111 ($170 dollars), which in today's money would be £5,200 ($8,200 dollars), to help starving Irish people during the Great Famine.

More than one million people died during the Great Famine, a period of mass starvation, illness, and emigration after disease blighted potato crops.

"I first became aware of the connection between the Choctaw and Ireland through a book I read at school," Waylon said.

Essay

"A teacher thought I wasn't working hard enough and I was sent to the library to write an essay.

"I opened a book and the first page I came to was about the Irish-Choctaw link."

Waylon, who is in his mid-60s, first came to Ireland in 1995 after living in Oklahoma all his life.

"A friend from Londonderry had introduced me to the work of Dublin-based Action From Ireland (AFRI), external, a humanitarian and social justice organisation," he said.

"Shortly after I made contact with them, they asked me to lead their annual famine walk in Mayo.

Waylon Gary White Deer (fourth right) leads an AFRI Famine Walk in Donegal

"That first visit in 1995 really brought home to me the link between the Choctaw and the Irish."

The Choctaw and the people of Ireland were in a similar situation at the time of the famine.

The Choctaw lived in south-eastern USA, but the American government forcibly removed them from their land to south-eastern Oklahoma in what became known as the Trail of Tears.

"We were both driven out of our homes and were victims of starvation and hunger-related diseases. And as dispossessed people we were trying to gather ourselves up again," said Mr White Deer.

Home

As well as working as an artist and author, Waylon is now a co-ordinator of the AFRI/Choctaw Famine Landscape Project, and has made Ireland his permanent home.

"It just kind of happened. I lived in Cork and then Dublin and moved to Donegal 15 months ago. The two cultures have a lot of similarities.

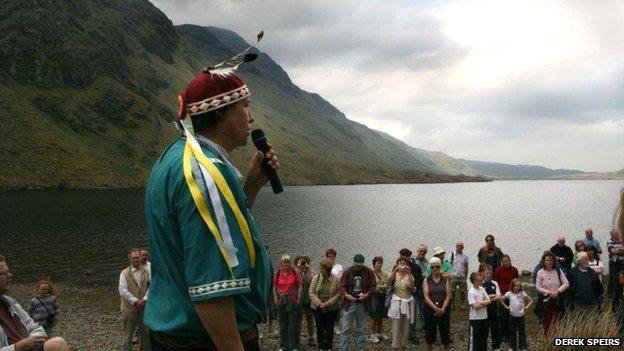

Waylon Gary White Deer addresses an AFRI Famine Walk in Mayo

"We have endured American colonisation, but we have kept our language and our songs and culture intact because they are very precious to us.

"I have found there to be a genuineness and a goodness in all Irish people, which is similar to the Choctaw.

"Also, the landscape in Ireland has a wild desolate beauty and desolate spirit which is very nourishing to me.

"I feel very at home."

Solidarity

Waylon's work with the Famine Landscape Project aims to keep alive the Irish-Choctaw famine link as well as standing in solidarity with those who still suffer from want of food and lack of social justice.

The project now includes AFRI's Famine Walks, which have been taking place since 1988.

Walk leaders have included Christy Moore, Denis Halliday, Damien Dempsey, Sharon Shannon and Andy Irvine.

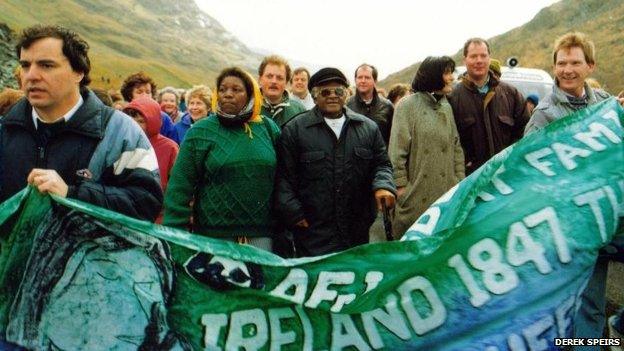

Desmond Tutu leading an AFRI Famine Walk in Mayo, in 1991

"The walks have three purposes," Waylon said.

"Commemorating those who died and identifying famine graveyards, so they are marked and treated with respect.

"To promote healing. Even though the famine happened more than 150 years ago, there is still a lot of shame and silence.

Trauma

"There is a phenomenon called inter-generational trauma. If something doesn't get resolved in one generation, it is passed down to the next.

"The third purpose is to stand in solidarity with those who still suffer hunger and injustice in a world of plenty.

"If we can turn those tragedies round, that's the way the circle can be completed, because that's the way it was started."

The next walk takes place on Sunday 30 August in Ballyshannon at 14:15 local time, starting from the town's former workhouse.