How can we wake our father in a nursing home?

- Published

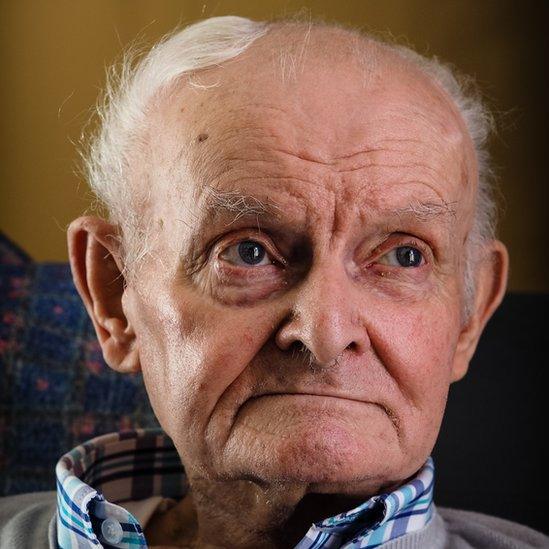

Photographer Feldore McHugh writes: "The inner spirit: My father, who had Alzheimer’s disease, holding a buttercup. He could no longer communicate, but he held this flower so delicately, and looked so intently at it, I could sense that he had been touched by its beauty”

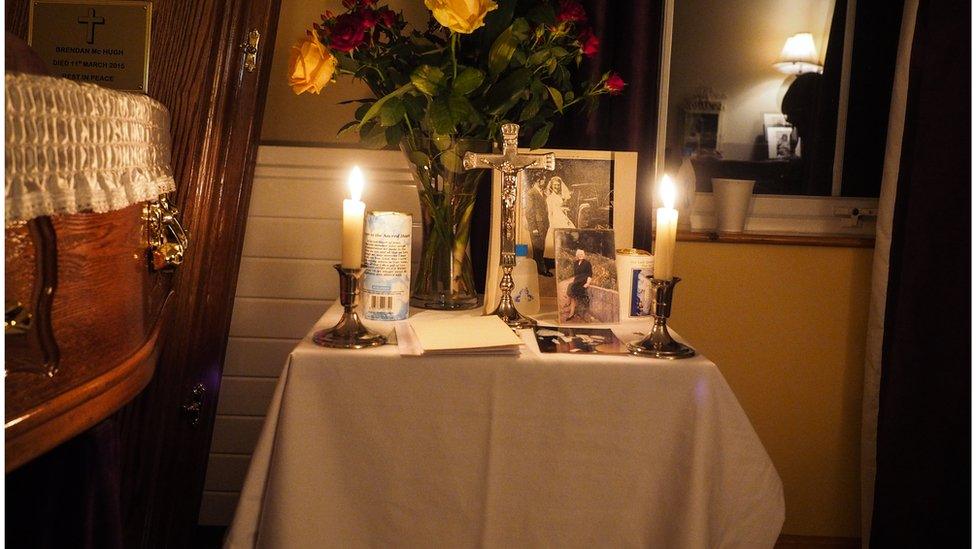

The traditional Irish wake is a gentle leave taking. It is a time for the soft flicker of candles, a crucifix and crisp white linen cloths.

The loved one's body is laid out in a quiet room; clocks are stopped at the moment of death, blinds are drawn down, friends and neighbours gather.

It is a long night's vigil - a watch over the dead one.

It is a time to weep, but also a time to smile and share a parting glass to celebrate the life that has passed.

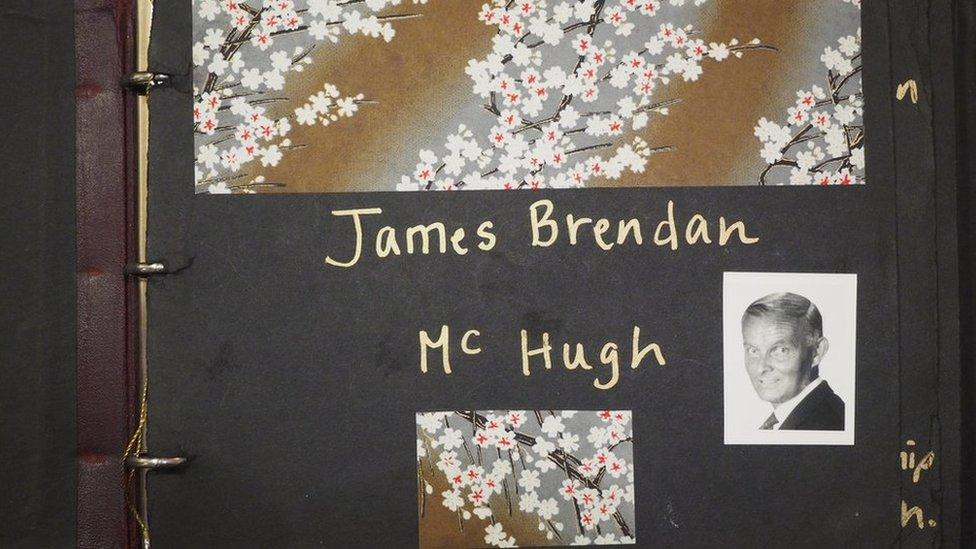

When Brendan McHugh went into the home, his family compiled a memory book about his life

Tea is served and more tea and more tea and whiskey and mountains of sandwiches are handed out to visitors. They stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the family in the face of loss.

'Bereft of words'

But how can you have a traditional wake in a nursing home?

When Brendan McHugh from Killyclogher, County Tyrone, died earlier this year at the age of 88, he had lived 10 years in the shadow of severe dementia. It was a stealthy thief, plundering his quick mind and leaving him bereft of words.

Final days at Slieve na Mon: Brendan McHugh with his grand daughter, Bunny on her last visit

All the more reason for his four children - Fionnuala and Declan, Eina and Feldore - to want to celebrate the bright, gifted man he once was.

Born in 1926 in Cliffoney, Sligo, he was often described as "a true gentleman" and an exquisite dancer. He was a life-long teacher, known to many as 'the Master' - the man to whom people turned for confidential help and advice.

Fionnuala McHugh with her father in 2014

He was a gifted gardener who was passionate about the beauty of the natural world.

"In the hard years of illness, so much seemed to have been taken away from him," said his daughter, Eina.

Feldore McHugh - who created this photo portrait - with his father in 2014

The family wanted a traditional wake for their father. They wanted the kind of leave taking that they had been able to give their mother, Nan. But she had died years earlier and the family home was no longer available.

Fionnuala, Brendan's eldest daughter, spoke often to the manager of Slieve Na Mon Care Center in County Tyrone where he spent the last eight years of his life.

Eina McHugh sharing time with her father in 2013

The home responded with understanding and compassion. Slieve Na Mon promised that, when the time came, he would be waked there.

Earlier this year, after some weeks in hospital, the family sensed he was dying.

A table was set out at Slieve na Mon for Brendan McHugh's wake

"We wanted him to come home. Home was Slieve na Mon," said Eina.

The home made good their promise. A bedroom was made available so that his children could stay close to their father over the long nights of his dying.

'Protective act'

The family was given a room so that they could eat and drink privately. A notice was put up asking visitors to move quietly as a family was sitting with a loved one.

"It felt like a protective act," said Eina.

When Brendan McHugh died, the clock in his room was stopped at the time of death

A table was set up in the entrance to the home with a lantern and candles.

When Brendan McHugh died on 11 March, the clock in his room was stopped at 5.10am - the precise time of death, an old Irish custom - and staff prepared for the promised wake.

A room was set aside for visitors, chairs were set out and food was prepared. This was a gift to the family.

Declan McHugh with his father in his final days

"Friends and relatives who came from Ireland, England and Scotland couldn't believe how accommodating Slieve na Mon was," said Eina.

"You could see people re-assessing their expectations of what was possible in a care home."

'Farewell'

The final parting came on a sunlit, frosty morning on Friday 13 March when Brendan McHugh's coffin was taken from Slieve na Mon to church in Killyclogher for his funeral.

"All the staff lined up on both sides of the entrance gate to bid farewell to our father," said Eina.

"The ceremonial guard of honour felt like a public act of recognition, of remembering. No gesture could have meant more."

What were his thoughts? He could no longer talk but the spirit was there

Joan McLaughlin, the manager of the nursing home, said "From 6pm to 8pm over two days, visitors were welcomed."

'Special time'

A palliative table with lanterns, candles and messages is practice at the home when someone is dying.

"We want everyone to know that family are spending quiet, special time with someone they love in their final days and hours," she said.

Brendan McHugh died at Slieve na Mon nursing home in March 2015

Each person who comes to Slieve na Mon is an individual and their families all want different things, said Joan. What Slieve na Mon tries to do is to honour that.

The guard of honour, made up of all the staff - nurses, carers, cooks, cleaners - is a ritual that has been in place since the home opened in the early 1990s.

Sarah Penney is a former manager of a nursing home and is project manager of My Home Life - an initiative across the UK to develop practice and improve quality of life in care homes.

Relationship-centred care

Sixteen managers, including Joan McLaughlin, took part last year and another 16 are preparing for the course, which is run through Ulster University.

There are currently 268 nursing homes in Northern Ireland, offering a total of 11,936 registered places, according to the latest figures from the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority (RQIA).

The course is about relationship-centred care, said Sarah.

One end is supporting a good end of life, maintaining dignity and identity.

"The whole project is about recognising that the person is an individual and supporting staff and residents though the process in whatever way is right for the family. That really differs from family to family," she said.

Happier times: Brendan McHugh with his wife, Nan in their beloved garden in 2003 before the full impact of Alzheimer's disease

Ms Penney said nursing home managers need positive support.

"When they come, you really have to build them up. It is important to share the good stories," she said.

"At our recent conference in Magee more than 170 people came. For the care home managers this was amazing. They got up and spoke and for people to be clapping and saying; 'You are really doing a good job,' that was very important."

'Little things'

It is the small things that matter.

"What families and friends remember about a home is not how fancy it is, but the little things like remembering to put on mum's glasses or giving her her favourite blanket," she said.

For the McHugh family, the nursing home's response to their suffering was a deep source of consolation.

"We often associate care homes with foreboding. There is not much positive coverage," said Eina.

"But where there is good practice such as we experienced, often that good practice goes unseen and uncelebrated.

"This care for my father and for our family was exemplary.

"I have had a lived experience of a Northern Irish care home doing really, really well in the dying process."