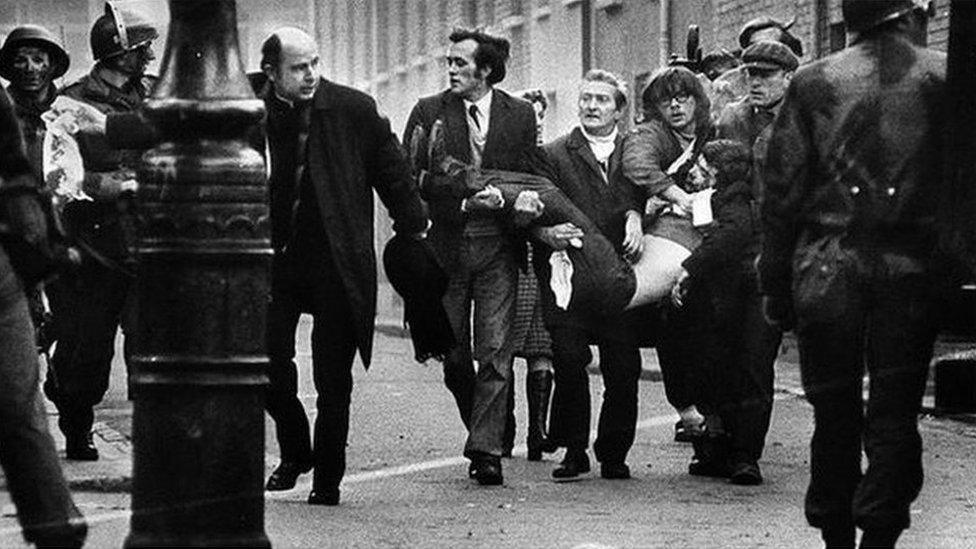

Bloody Sunday arrest highlights sentence differences

- Published

- comments

Currently, a former paratrooper convicted of a crime on Bloody Sunday would not qualify for early release

During an interview about the Stormont talks, I asked the secretary of state a question relevant to the arrest of a former soldier for questioning about the Bloody Sunday killings in Londonderry.

Was she comfortable with the situation, I asked, that an ex-soldier found guilty of a Troubles offence would have to serve their full term in jail, while an ex-paramilitary could avail of the early release scheme introduced as a result of the Good Friday Agreement?

Theresa Villiers replied that the law must apply to everyone, but the differential in sentencing was "one of the very difficult decisions" taken in the run-up to the Good Friday Agreement.

She confirmed that during the current discussions on the legacy of the Troubles there are no plans to alter the differential.

However, it's not quite as simple as one rule for soldiers and police and another for paramilitaries.

To be fair to Theresa Villiers, my brief summary of the scenario wasn't accurate.

As things stand, a former paratrooper convicted of a crime on Bloody Sunday won't qualify for early release, but that isn't because they belonged to the security forces.

Scheduled offences

Instead it's due to the Northern Ireland Sentencing Act 1998 which does not apply to any offences committed before the Emergency Provisions Act came into force in 1973.

The 1973 act introduced "scheduled offences" to be tried before no-jury Diplock courts. In the main, those cases involved former paramilitaries because it was feared juries would be subject to intimidation.

But during the Troubles there were also judge only trials of soldiers like Lee Clegg, external or Guardsmen Mark Wright and James Fisher, external.

Senior legal sources tell me if a soldier is convicted in the future of what would have been deemed a scheduled offence between 1973 and 1998, they could apply for early release under the Good Friday Agreement.

However, that still leaves an anomaly in respect of crimes carried out between the start of the Troubles in 1969 and 1973.

This came to my attention last year at the time of the publication of the Hallett Review into the so-called "on the runs".

A Northern Ireland Office source told me the previous Labour government had used the Royal Prerogative of Mercy to free a few individual paramilitary prisoners convicted at the start of the 1970s "who fell outside the letter of the NI Sentences Act" but "within the spirit of the (Belfast Agreement) legislation".

Theoretically the current government could adopt the same approach of issuing pardons to any soldier convicted of a crime related to Bloody Sunday.

Alternatively they could amend the 1998 Sentencing Act to make early releases apply to crimes dating back from the very start of the Troubles.

That may partially appease former officers like Colonel Richard Kemp who believes the Bloody Sunday arrest is "another example of the government allowing soldiers to be hounded through the courts".

But either course of action would risk infuriating those families of the Bloody Sunday victims who want to see justice done for their loved ones.