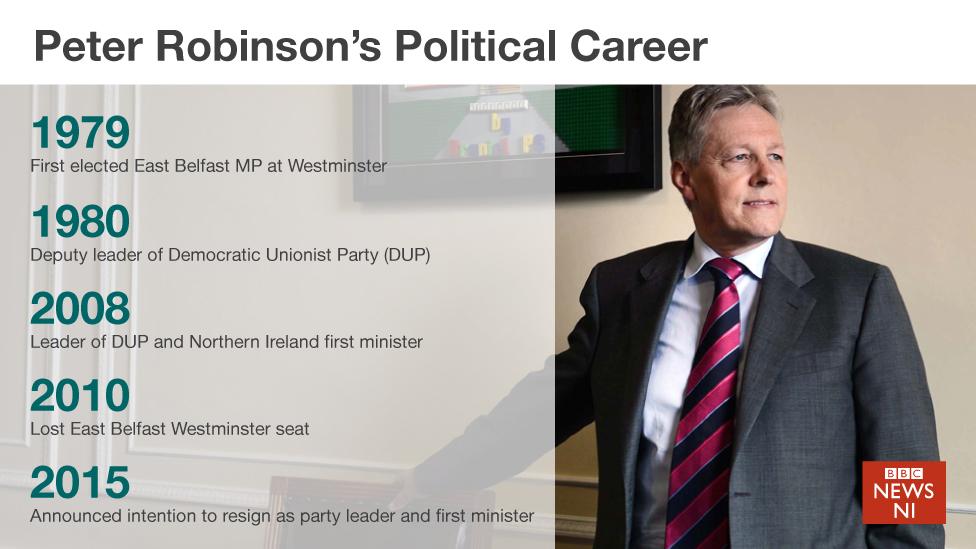

Peter Robinson: Leadership and legacy of a 40-year career

- Published

Peter Robinson will step down from his roles as Northern Ireland's first minister and DUP leader within weeks

In politics - as in other walks of life - it pays to trust your instincts.

In 2010, Peter Robinson's instincts told him not to stand in the general election. He ignored them - and lost.

It was a mistake he was unlikely to make again when it came to his other jobs as first minister of Northern Ireland and leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

The "why now" question is easy.

Firstly, the East Belfast seat was recaptured in May, even though it took a unionist pact to allow Gavin Robinson (no relation) to defeat Alliance's Naomi Long.

Secondly, Tuesday's Fresh Start deal, external with Sinn Féin offers some stability to the Stormont institutions after a year of uncertainty.

Certainly it should stave off fears of an early assembly election - which the DUP did not want - and allows the new leadership team time to get bedded in ahead of the poll which will now take place as planned in May.

And last but not least, it allows Mr Robinson his valedictory moment at the DUP conference this weekend.

The decision to announce his departure ahead of the conference takes the edge off the event and makes it more of a lap of honour.

There was never much chance of Mr Robinson leading his party into the assembly election in any case.

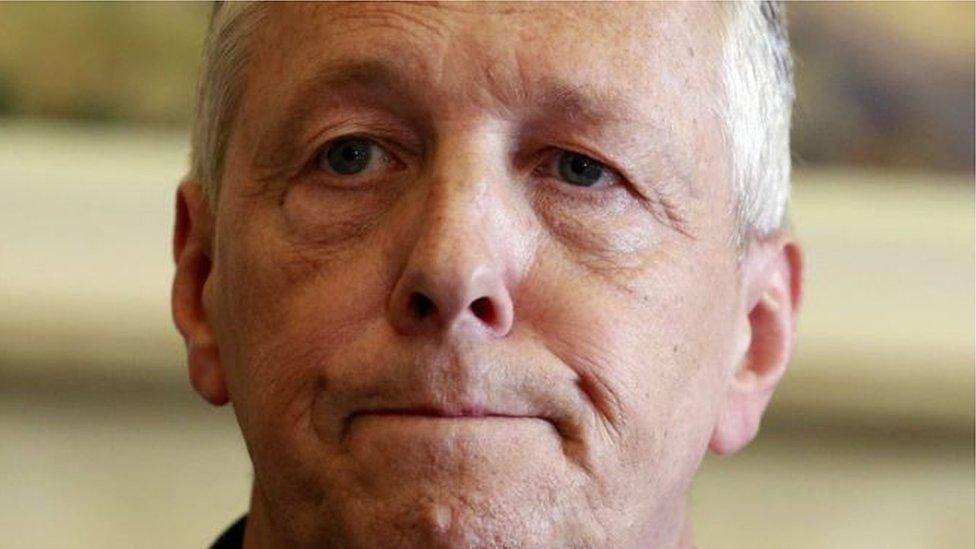

The past few years, both personally and professionally, have been turbulent for the 66-year-old leader.

Master strategist

He has faced the trauma of his wife Iris's break-down and affair with a much younger man; and he faced major health problems, suffering a heart attack earlier this year.

The way he dealt with both of those issues garnered widespread admiration.

But there has been less admiration for the way he dealt with Stormont's most recent crisis, and, in particular, the rolling resignation policy of DUP ministers which was much criticised.

Mr Robinson, however, may say it was better than the alternative - pulling down the institutions altogether.

He has also had to deny allegations he was to benefit financially as a result of Northern Ireland's biggest ever property deal involving the Republic's so-called bad bank, Nama (National Assets Management Agency).

If any of this caused rumblings behind the scenes none of it broke the surface of a party which Mr Robinson leaves as tightly disciplined as it was when he joined it.

Martin McGuinness said he considered Peter Robinson to be a friend

But it is bound to have caused disquiet and made some members wonder if the party might be safer to enter the assembly election under new leadership.

Certainly it will be difficult for the DUP to match its result last time when they were generally felt to have over-achieved by returning with 38 MLAs.

Add to that signs of resurgence in the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and there may never be a better time for Mr Robinson to bow out.

Nevertheless, his unrivalled ability as a master strategist is still likely to be missed, whoever takes over.

The past few years have been turbulent for the 66-year-old

Just as his departure is not a surprise, neither will it be a shock if he is replaced by Nigel Dodds as party leader and by Arlene Foster as first minister.

Transformation

After all she has had on-the-job training when Mr Robinson stepped aside to deal with his personal problems and recently over allegations of IRA involvement in the murder of Kevin McGuigan.

His legacy may be two-fold. The transformation of the DUP from a minority party of protest into a vote-winning machine which trampled all before it in the crowded electoral world of unionism.

And secondly his transformation from the hardliner who once led a loyalist "invasion" of the County Monaghan village of Clontibret into the pragmatist who came to terms with - and set the terms for - going into government with Sinn Féin.

Neither of these achievements is likely to make him any more loved by his many detractors but should surely secure him a significant place in the pantheon of unionist leaders.