2015 in review: Politics in Northern Ireland

- Published

2015 was a tumultuous year in Northern Irish politics

With two new party leaders and three new MPs, 2015 was a year that saw plenty of change when it came to Northern Ireland politics.

Not for the first time, Stormont appeared to be close to suspension or financial breakdown.

And not for the first time, the politicians found their way back from the brink.

Although this time, much to the relief of the Stormont press pack, their talks did not run into the Christmas period.

The year began with plenty of dates for the politicians to mark in their diaries.

The Stormont House Agreement, reached on the day before Christmas Eve 2014, set out a series of targets related to the Northern Ireland Executive's budget, the implementation of controversial UK-wide welfare reforms and the creation of an opposition at Stormont.

But the choreography did not roll out according to plan.

Welfare Reform

Martin McGuinness called the situation over welfare reform a 'crisis that needs to be averted'

In March, Sinn Féin pulled the plug on the Welfare Reform Bill before it reached its final stage.

The party argued that a package designed to mitigate the cuts would not be as comprehensive as it had been led to believe.

Its main partner in power, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), accused Sinn Féin of "dishonourable and ham-fisted" tactics.

The move put a question mark over the financial viability of the executive, as the UK government made it clear it would not release loans promised in the Stormont House deal, and would continue to levy fines related to the failure to revamp the benefits system.

With the future of Stormont in question, the local parties turned their minds to their own fates in May's Westminster election.

The May elections

Many commentators expected a "hung parliament", so the DUP made great play of potentially holding the UK balance of power, something that, with the outright Conservative majority, didn't come to pass.

One of the fiercest contests took place in East Belfast where the DUP's Gavin Robinson wreaked revenge on behalf of his leader and namesake Peter Robinson by winning the seat back from Naomi Long of the Alliance Party.

The DUP were greatly assisted in recapturing East Belfast by an election pact with the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP).

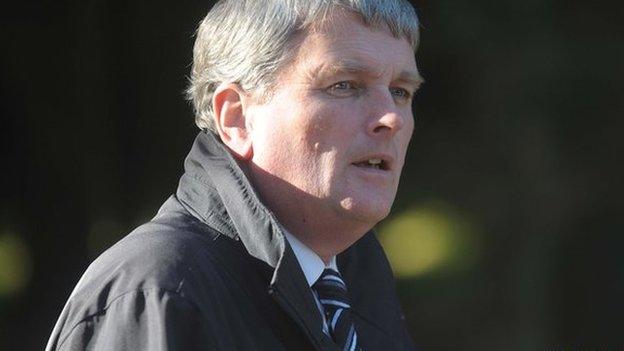

They repaid the favour in the Fermanagh and South Tyrone constituency, where the Ulster Unionist Tom Elliott took the seat from Sinn Féin's Michelle Gildernew by more than 500 votes.

Although the DUP and UUP reached tactical deals in some Westminster seats, in other places they fought each other as hard as ever.

In Upper Bann, Jo-Anne Dobson failed to unseat the DUP's David Simpson, but in South Antrim the UUP's Danny Kinahan defeated the veteran DUP politician William McCrea by more than 900 votes.

The return of two Ulster Unionist MPs to the green benches meant the party's leader Mike Nesbitt emerged from the May election as a clear winner, while the defeat of both Mrs Gildernew and Mrs Long lowered the profile of local women in politics.

Controversy

Away from the results, though, the election yielded one extraordinary story when the then Health Minister Jim Wells, of the DUP, made controversial remarks about same-sex marriage and the abuse of children in unstable relationships.

A video of his remarks at an election hustings event in Downpatrick in County Down went viral.

Although Mr Wells maintained his comments had been misconstrued, a further incident when he was canvassing a lesbian couple in Rathfriland in County Down led to his resignation as a minister.

The controversy played out against a particularly tragic backdrop as Mr Wells' wife lay seriously ill in hospital.

Back at Stormont, the DUP reshuffled its team, switching Simon Hamilton from the finance portfolio to health, with Arlene Foster moving to the finance department from from enterprise.

Stormont finances

Finance Minister Arlene Foster presented details of a budget in June, in what some critics called a "fantasy"

With no movement on welfare reform, Stormont's financial situation appeared ever more dire.

In late May, Mrs Foster predicted that a massive £2.8bn cut might be imposed if civil servants had to take over the reins of power and introduce an emergency budget.

But this doomsday scenario was avoided when she pressed ahead with what commentators called a "fantasy budget", in which she pretended that welfare changes that remained open to dispute had in fact been agreed.

It seemed a bizarre development, but it was not the last time during 2015 that the DUP would adopt strange tactics to keep the Stormont show on the road.

Kevin McGuigan Sr

Kevin McGuigan Sr was shot dead close to his home in August, sparking a political crisis

In August, the murder of a former IRA member in Belfast, in apparent revenge for the murder of another leading republican in May, added a more sinister element to what had previously been a crisis at Stormont over financial and social policy.

The police's suspicion that current IRA members might have been involved in the murder of Short Strand man Kevin McGuigan Sr turned the clock back to the 1990s when the stability of power-sharing was frequently threatened by questions about whether the IRA had gone away.

In that earlier era, the Ulster Unionists took a constant pounding from the DUP who criticised them for sharing power with republicans.

So perhaps some in the UUP could be forgiven for indulging in a sense of schadenfreude when Mike Nesbitt pulled his only minister, Danny Kennedy, out of the executive in response to the police briefings over Mr McGuigan's murder.

The move initially wrong-footed the DUP, who called for Sinn Féin's exclusion from government.

After a senior Sinn Féin official was arrested for questioning about the killing, DUP ministers appeared to follow the Ulster Unionists' lead by handing in their resignations.

But there was a crucial difference - the DUP ministers kept their portfolios in limbo by resuming their jobs then immediately resigning again, a tactic that they repeated.

The DUP's critics lampooned the manoeuvre as "hokey-pokey" politics.

The move generated negative publicity but bought crucial time for fresh negotiations.

The Sinn Féin official was released without charge and, even though an official security assessment suggested the IRA Army Council might still play a role in overseeing Sinn Féin, the DUP ministers returned to their jobs full time and pressed ahead with another attempt to resolve the executive's outstanding difficulties.

Before that came to fruition, though, another of the Stormont parties experienced internal upheaval.

SDLP Leadership

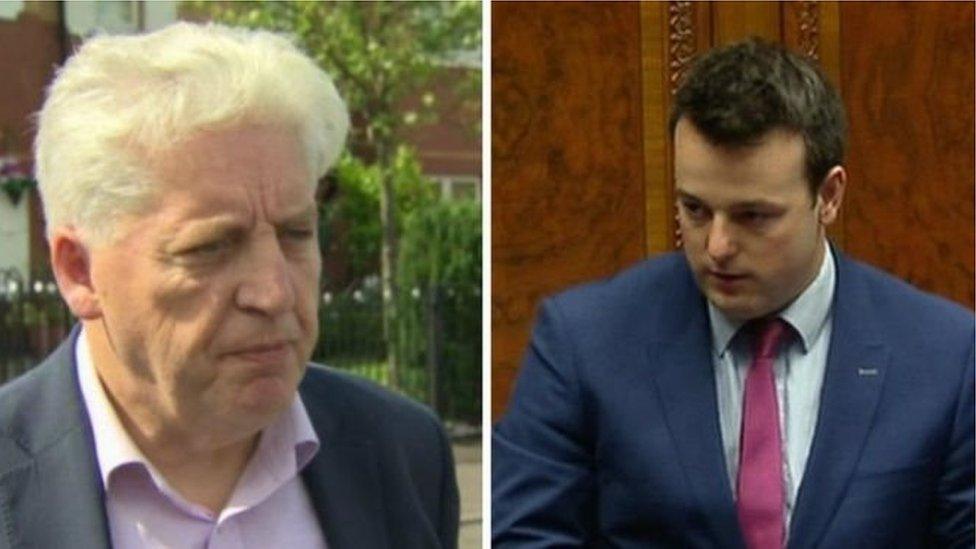

Alasdair McDonnell was replaced as SDLP leader by Colum Eastwood

Alasdair McDonnell successfully defended his Westminster seat in South Belfast during a hard-fought personal campaign.

But that did not stop his critics within the SDLP complaining about his leadership.

The 32-year-old Foyle MLA Colum Eastwood decided to run against Dr McDonnell at the party's conference in November, and the bold gambit paid off as delegates voted by 172 votes to 133 to give a younger generation a chance.

The SDLP was not the only party to hold its conference in November.

As the DUP's gathering loomed closer at the end of November, there was an increasing sense that it might serve as a bookend both for the latest inter party talks and the career of the First Minister Peter Robinson.

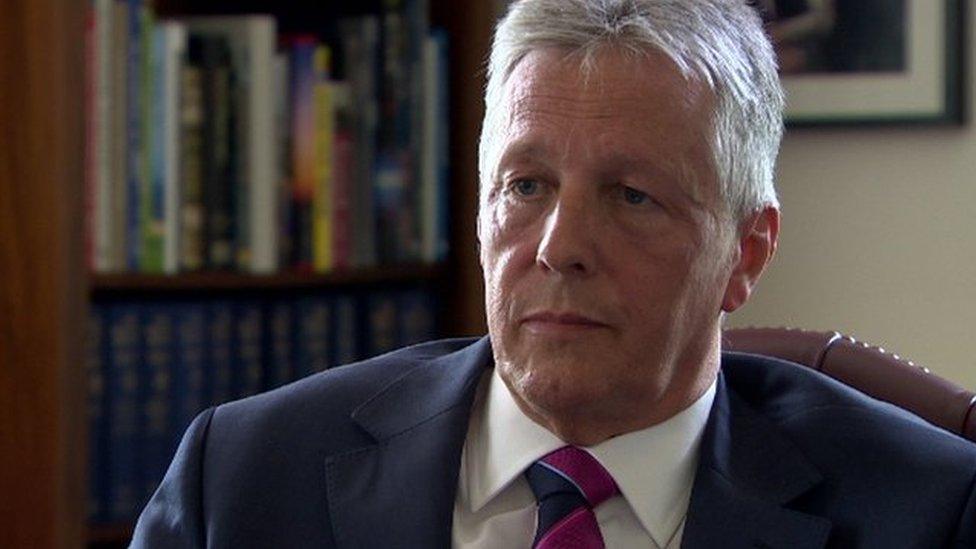

Peter Robinson

On a personal level Mr Robinson had experienced an extremely tough year.

In May, he was rushed to hospital after suffering a heart attack, something he later blamed on his lack of exercise and diet of "cowboy suppers".

He returned to work but there were occasions when he was clearly hampered by complications related to his treatment.

On top of this, the first minister faced questions about his handling of a massive property deal in which the £1.2bn Northern Ireland portfolio owned by the Republic of Ireland's so-called 'bad bank', the National Asset Management Agency, was sold to the US firm Cerberus.

The loyalist blogger Jamie Bryson used the privilege accorded to a meeting of Stormont's finance committee to claim Mr Robinson was one of a number of people hoping to benefit from multi-million pounds fixer fees associated with the deal.

The first minister strenuously denied the accusation, insisting that his involvement in discussions about the deal had been purely motivated by wanting to stimulate the wider Northern Ireland economy.

Fresh Start deal

Theresa Villiers said the deal reached represents "fresh start for Northern Ireland's devolved institutions"

With the DUP conference in sight, the two main local parties and the British and Irish governments unveiled their Fresh Start deal.

The welfare reforms resisted by Sinn Féin would now be implemented by Westminster legislation.

The move would free up Treasury loans that would put Stormont back on a more stable financial footing.

A mitigation package would assist those hit hardest by benefits cuts and reduced tax credits, although the chancellor later withdrew his threat to cut the credits.

The DUP and Sinn Féin hailed the deal as the best option available.

But their critics insisted the Fresh Start was a false start, not least because it did not cover the vexed issue of setting up new agencies to deal with the legacy of the Troubles.

The rights and wrongs of the Fresh Start are likely to provide much of the battleground for the 2016 Northern Ireland Assembly election.

A new DUP Leader

Mr Robinson spoke to BBC Northern Ireland's political editor Mark Devenport about the timing of his announcement.

Mr Robinson will not be in the front line of that struggle.

One day after the deal he confirmed his departure as both DUP leader and first minister.

At an emotional DUP conference, it looked like a "dream team" of Nigel Dodds as leader and Arlene Foster as first minister would be anointed as Mr Robinson's joint successors.

But Mr Dodds, the North Belfast MP, surprised observers by deciding not to contest the leadership, arguing that in the days of devolution the DUP could not be led from Westminster.

The East Antrim MP Sammy Wilson briefly considered running his own campaign.

But when he decided against standing as a leadership candidate, the election of Arlene Foster as both DUP leader and first minister became a coronation.

BBC News NI looks back at some of the memorable moments that have defined the DUP's Arlene Foster

Mrs Foster is the DUP's first woman leader and, as an Anglican and former Ulster Unionist, she represents a break from the party's Paisleyite Free Presbyterian roots.

2016

The new leader will no doubt focus on the assembly election, in which she will hope the DUP does not lose its top spot to Sinn Féin, nor the first minister's title which goes with it.

Martin McGuinness says if Sinn Féin was to be the biggest party he would be relaxed about renaming the two top jobs as "joint first ministers", external.

Before he gets to that place, though, Mr McGuinness's attention will no doubt be deflected by the forthcoming Irish parliament election, in which Sinn Féin hopes to advance its all Ireland agenda.

There's also the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising that will have inevitable resonance for Irish nationalists, and potentially for unionists if the angry reaction to a stunt in which a 1916 flag and an Irish tricolour were briefly raised over Stormont is anything to go by.

Aside from constitutional issues, the parties will continue to grapple with sensitive moral and social questions concerning abortion, same-sex marriage and blood donation.

And then, of course, there is the unexpected.

As 2015 proved, no year at Stormont unfolds according to any plan laid out before our MLAs on 1 January.

- Published9 March 2015

- Published8 May 2015

- Published27 April 2015

- Published21 May 2015

- Published8 June 2015

- Published20 August 2015

- Published26 August 2015

- Published10 September 2015

- Published15 November 2015

- Published23 September 2015

- Published18 November 2015

- Published17 November 2015