Easter Rising 1916: Six days of armed struggle that changed Irish and British history

- Published

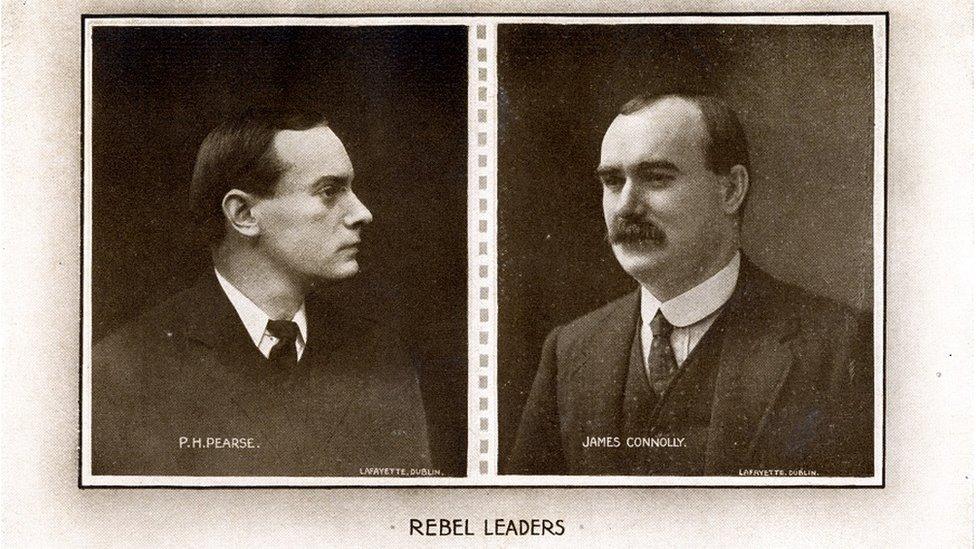

Pádraig Pearse and James Connolly, two of the leaders of the military council

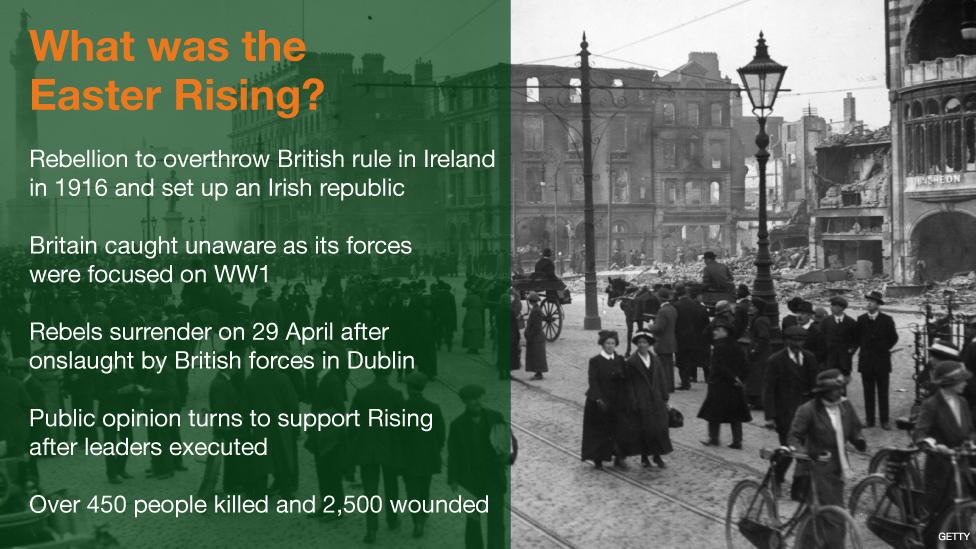

The years leading up to the rebellion against British rule in Ireland in April 1916 were marked by significant political, cultural and military developments in Ireland and throughout Europe.

The rebellion became known as the Easter Rising.

Home Rule came to dominate domestic British politics in the era from 1885 to the start of World War One.

Under Home Rule, Ireland would be given more say in how it was governed while continuing to remain part of the United Kingdom.

More than 100 years earlier, Ireland lost its parliament in Dublin and was governed directly from Westminster as a result of the Act of Union in 1800.

The threat of Home Rule led unionists in Ulster to establish the military organisation, the Ulster Volunteer Force, which in turn prompted the formation of the Irish Volunteers.

The emergence of these forces undermined British rule in Ireland.

However, the possibility of violence in Ulster was averted by the outbreak of World War One.

The main party in favour of Home Rule, the Irish Parliamentary Party, agreed that attempts to secure self-governance should be postponed for the duration of the war.

Many Irishmen joined the call to arms and fought in western Europe.

However, others were angered by what they regarded as the Irish Parliamentary Party's acquiescence to Westminster.

The Irish Citizen Army, a socialist militia, led by James Connolly also played an important role in the rising

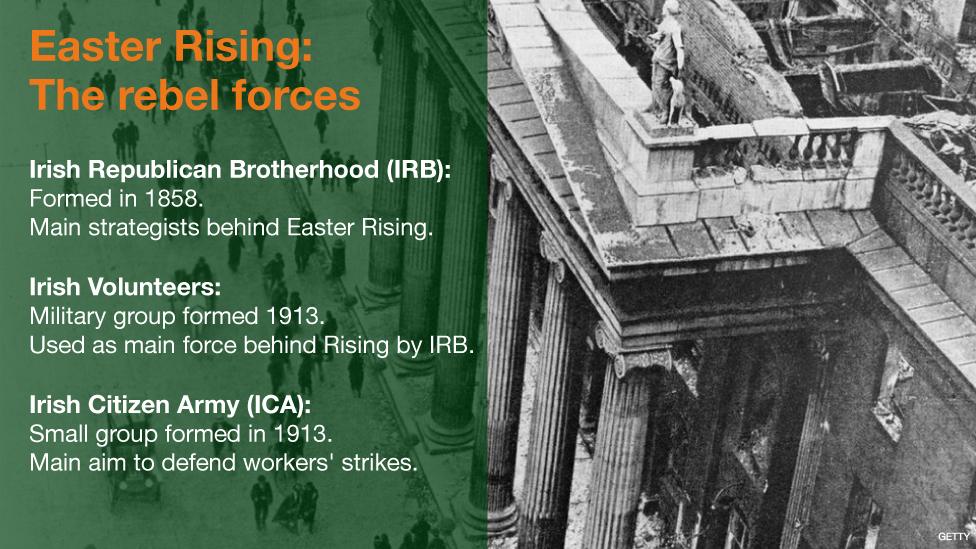

Three groups were behind the rising but the most important was the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) which was formed in the mid-19th century.

Thomas Clarke and Seán Mac Diarmada were the key figures in the IRB.

The Irish Volunteers were a military group formed in 1913 and its members accounted for the largest number of men who were called out on Easter Monday.

The Irish Citizen Army, a socialist militia, led by James Connolly also played an important role.

Over 200 women, most members of Cumann na mBan, the 'League of Women', also played a role in the rising.

The key group was a seven-man IRB military council, drawn from those three organisations, which planned the Easter Rising with complete secrecy.

The decision to rise was based on the traditional dictum that England's difficulty was Ireland's opportunity.

But it also reflected the military council's fear that Irish nationalism was in decline, a concern reinforced by popular Irish nationalist support for the aims of the Irish Parliamentary Party and the British war effort.

On 23 April, the council agreed to proceed with the rising the next day, Easter Monday.

The drafting of a proclamation declaring the establishment of a republic was one of the final steps taken by those who planned the rising.

It decided that the proclamation should be read to the public outside Dublin's General Post Office (GPO) by the president of the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic.

Irish Volunteers barricade Townsend Street, Dublin, to slow down the advance of troops, during the Easter Rising

Despite Thomas Clarke's seniority, it was agreed that Pádraig Pearse should act as president.

Shortly after noon on Easter Monday, Pearse accompanied by an armed guard, stood on the steps of the GPO and read the proclamation, signalling the beginning of the Easter Rising.

Ireland's 'national right to freedom and sovereignty' was asserted.

The conflict that followed was largely confined to Dublin.

The British military onslaught, which the rebels had anticipated, did not at first materialise.

When the rising began, the authorities had just 400 troops to confront roughly 1,000 insurgents.

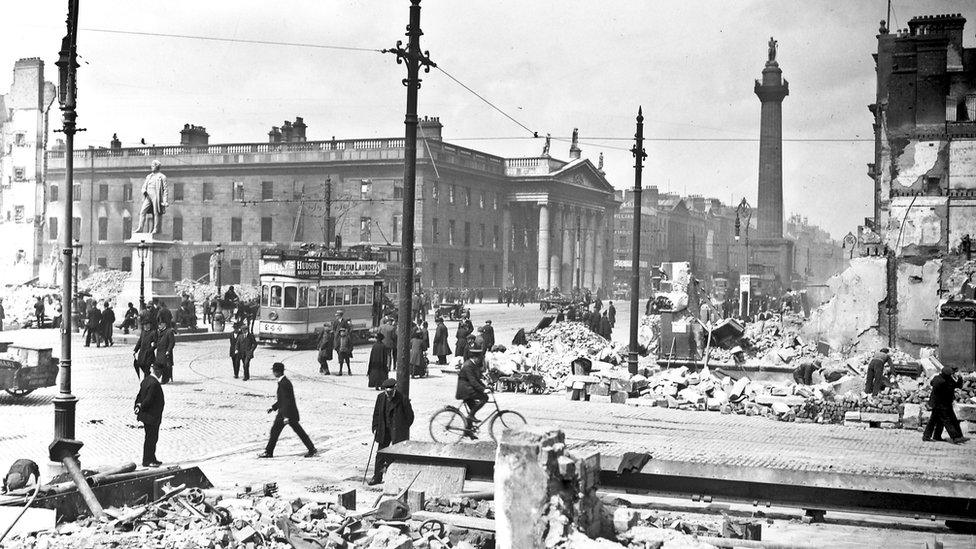

Crowds in Sackville Street (now O'Connell Street) can be seen next to the General Post Office showing damage from shelling following the Easter Uprising

As the week progressed, the fighting in some areas became more intense, leading to several prolonged, fiercely contested street battles. Military casualties were highest at Mount Street Bridge.

By Friday 28 April, about 18-20,000 soldiers had been amassed in the capital against about 1,600 rebels while much of the city centre had been destroyed by British artillery fire.

The next day, Pearse surrendered unconditionally on behalf of the Volunteers and issued orders to this effect.

A total of 450 people were killed during the rebellion, among them 64 rebels. 2,614 were injured, and nine others were reported missing, almost all in Dublin.

The British capture of a shipment of German arms three days before the rebellion was partly responsible for the failure of the nationwide mobilisation.

In addition, confusion was caused by conflicting orders sent out to the Irish Volunteers by their leader Eoin MacNeill,

Dr Fearghal McGarry, from Queen's University Belfast, said although there was very little support for the rising at the time, it was enormously successful in terms of what the organisers of the rising wanted to achieve.

"They did not expect it to win power, what they planned was a spectacle, a gesture to transform public opinion," he said.

"They knew they would not win, they knew some of them would die."

He said that, in political terms, the rising achieved everything that the organisers thought it would.

"It destroyed the Irish Parliamentary Party's credibility and it derailed Home Rule," he said.

"It exposed the oppressive nature of British rule and it transformed public opinion by winning public support for republicanism.

British soldiers parading in front square of Trinity College Dublin in the aftermath of the Easter Rising

"What might have surprised the leaders was how quickly all this happened. Within a year and a half republicanism had become the most important movement in Ireland."

Dr McGarry suggests that, for many Irish people, the significance of the rising lies less in the events of Easter week than in their longer term legacy.

"I think for most Irish, certainly people south of the border, the event's significance is not primarily centred on the week-long violence that took place in Dublin," he said.

"Rather it's focused on the attainment of Irish sovereignty, self-determination.

"It's bound up with national identity. In contrast, the rising's significance for many northern nationalists over the past century reflects partition and the failure to achieve a united Irish Republic.

"In the south, the rising is increasingly seen as history, not politics."