EU referendum: Farmers, fishermen and firms consider vote's consequences

- Published

Michael Harnett and his daughter Jane run farms in both Northern Ireland and off the coast of the Republic of Ireland

Farmers, fishermen and firms are divided in their opinions about a possible so-called Brexit - a UK withdrawal from the European Union - ahead of the 23 June referendum.

Michael Harnett grows crops in County Down and he loves big machines.

He also uses a huge landing craft to access a sheep farm he runs on an island off the County Mayo coast.

He believes farmers would be better off out of the European Union, producing food that people want and innovating to add value to it.

Jane Harnett says she believes in what the EU stands for

His family uses the crops he grows to produce artisan cooking oils that are sold in shops and used in restaurants.

He says people need to place a lot more value on their food and the people who grow it.

"Farming used to be something you were proud of," he says.

"You'd have been proud for your daughter to marry a farmer, now that's the last person you'd want them to marry - it's all stress and no money."

LacPatrick's Gabriel D'Arcy says he worries about the impact a Leave vote could have on the business

His daughter Jane helps run the farm but she is a committed European.

She has held that view since a school trip to the war graves and believes the EU has cemented peace on the continent.

"I believe in what it stands for," she says.

And while she knows things are not perfect, she thinks there is still a future in farming for young people like her.

Milk collected in Northern Ireland crosses the Irish border to LacPatrick's Monaghan base every day for processing

The LacPatrick Group is a dairy co-operative with 1,100 farmers, half of them in Northern Ireland.

Its County Monaghan headquarters is just a few miles from the former customs post at Aughnacloy in County Tyrone.

Thousands of litres of milk collected in Northern Ireland cross the Irish border every day for processing.

Gabriel D'Arcy, the LacPatrick's chief executive, worries about the impact of an exit on his business.

Rules on stock sustainability have cut the white fish fleet to just a handful of boats

Would controls mean delays which would cost money and dent profits?

Would the company face trade barriers like quotas or tariffs?

Mr D'Arcy also worries about how long it would take the United Kingdom to negotiate trade deals with west African countries.

LacPatrick exports lots of milk powder to those countries from its facility at Artigarvan in County Tyrone, which is undergoing a £30m upgrade.

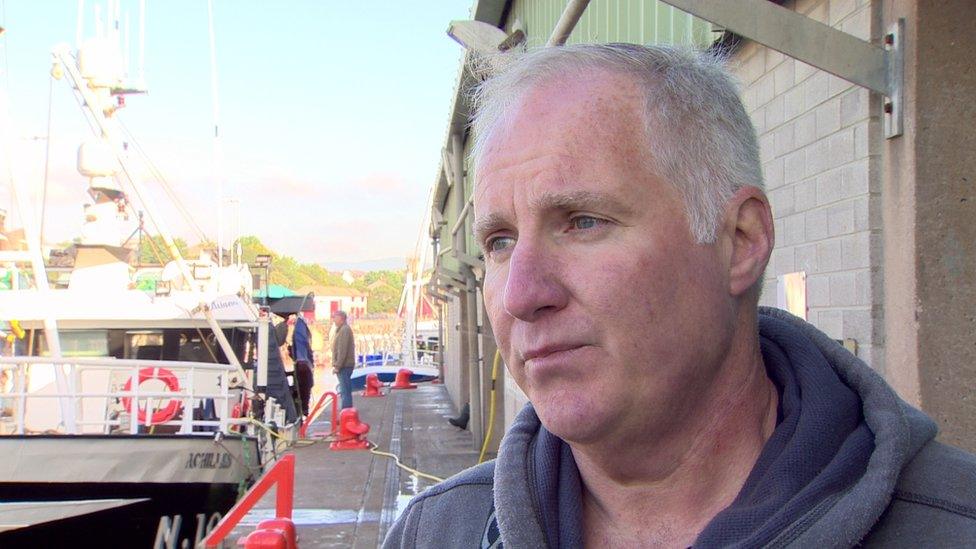

Trevor McKee says fishermen are united in their desire to see the UK leave to EU

Those shipments are covered by an EU trade deal.

Mr D'Arcy says: "What would be the terms of those agreements that would have to be renegotiated with Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Cameroon?

"They're our main markets for the products coming out of the Artigarvan facility."

While big business can see the benefits of EU membership, the self-employed fishermen from Northern Ireland's coastal communities take a vastly different view.

Mr McKee says Europe dictates how and when he can fish and what he can catch

Almost to a man, they want out and some are even flying flags on their vessels in support of the leave campaign.

Kilkeel fisherman Trevor McKee blames the EU's common fisheries policy for decimating an industry that he says had been sustainable for decades.

"Europe dictates how and when I can fish and what I can catch," he says.

"Fishermen have a better understanding of the stocks in the Irish Sea than a Brussels bureaucrat."

Mr McKee says fishermen have a "better understanding of the stocks in the Irish Sea than a Brussels bureaucrat"

Rules on stock sustainability have cut the white fish fleet to just a handful of boats and most of them are now fishing for prawns.

Mr McKee worries about the future of fishing if the UK stays in the EU.

"Everybody who goes to sea to fish is for out," he says.

"It's a no-brainer, because of the EU."

- Published30 December 2020

- Published29 April 2016