Past meets present in 'bittersweet' day for Loughinisland families

- Published

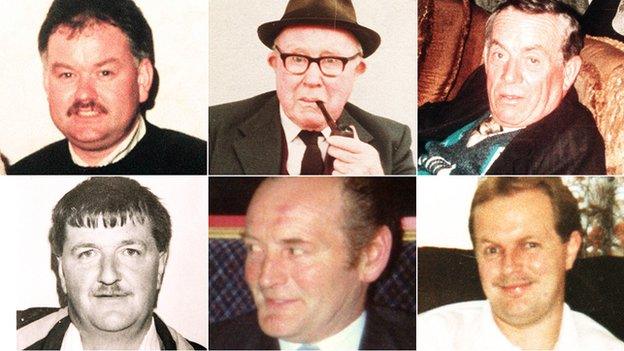

Families of some of those who died in Loughinisland speaking after the publication of the report

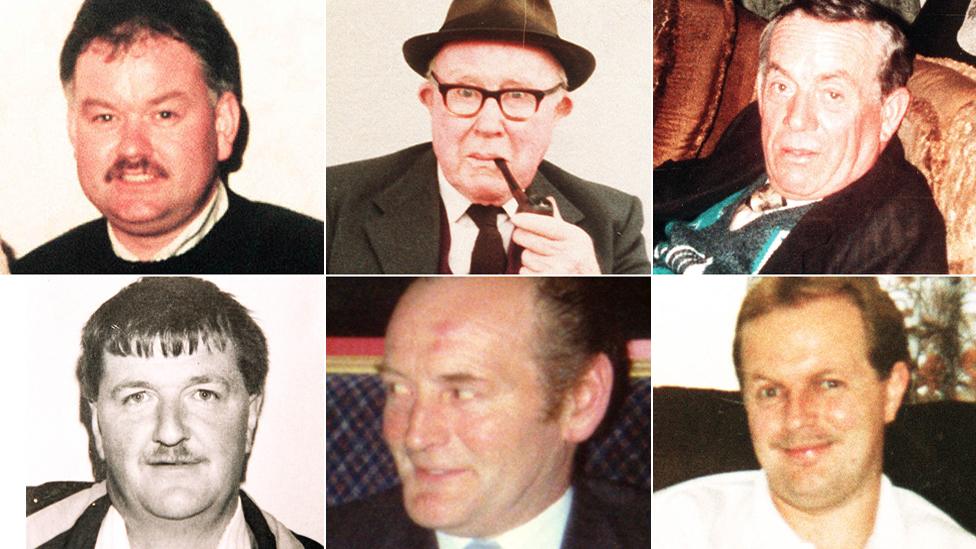

For the families of the men killed in Loughinisland, the findings of the Police Ombudsman were, in their words, "bittersweet".

It was the truth that the last ombudsman failed to discover in an earlier investigation five years ago.

This new document laid bare the failings that allowed their loved ones to be murdered.

And the actions which ensured that the loyalist gang who killed them were able to escape prosecution.

They are not the first relatives in Northern Ireland to have to fight to uncover what, in their hearts, they already knew.

Over the past decade, ombudsman reports, fresh investigations and inquests have all succeeded in confirming the worst fears of families in many attacks.

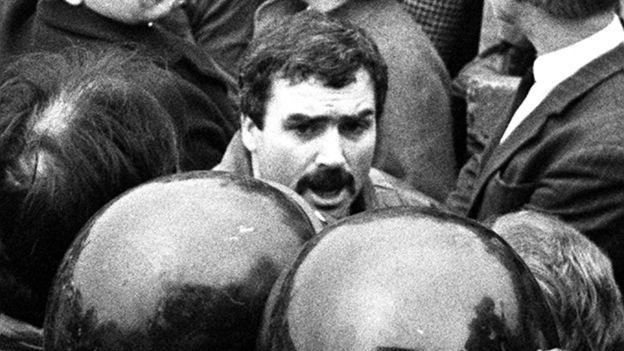

Fred Scappaticci denies he was an Army agent inside the IRA

And make no mistake, there are more murky secrets to be uncovered about the Troubles.

The long-awaited Stakeknife investigation is about to begin.

It will examine the actions of the man alleged to be one of the most important state agents from the brutal years of violence in Northern Ireland - and perhaps the most murderous.

It has been claimed that the informant Freddie Scappaticci - known as Stakeknife - was involved in dozens of IRA killings.

However, it is thought he was protected from prosecution because of the valuable information he was providing to the security forces and security services.

Mr Scappacticci, originally from west Belfast, has denied the allegations.

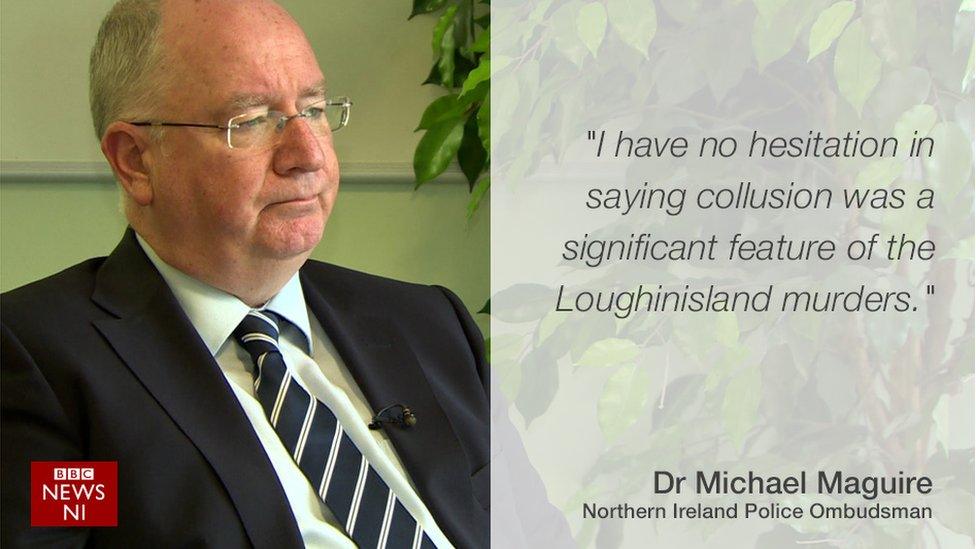

In the case of Loughinisland, Police Ombudsman Dr Michael Maguire was damning about the approach of the Royal Ulster Constabulary's Special Branch.

He said they had a "see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil" approach to informants.

In practical terms, officers turned a blind eye to their crimes in return for knowledge.

The government and the police have, in the past, pointed out that lives were saved by those who did the dangerous work of infiltrating paramilitary organisations.

But what was the wider cost?

The phrase "getting away with murder" rarely felt more appropriate.

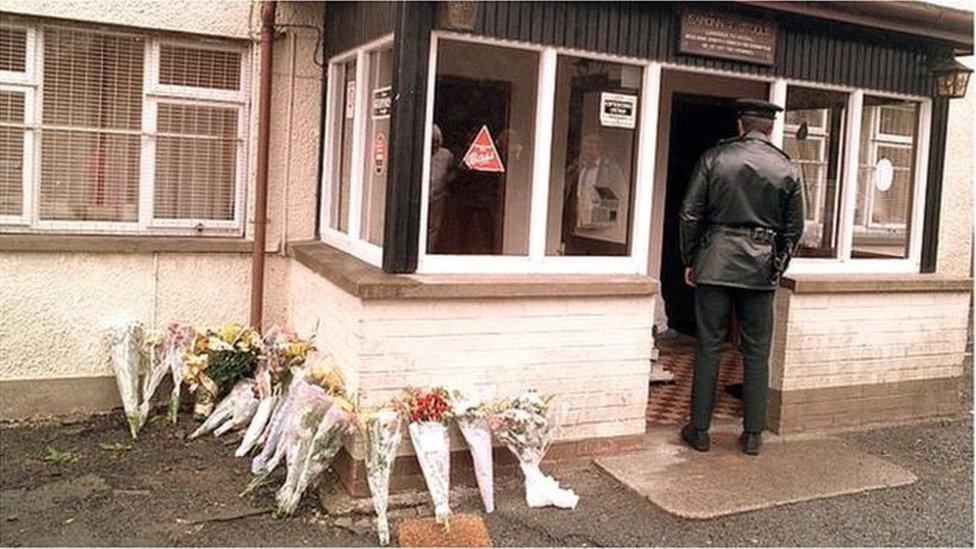

The attack in Loughinisland took place on 18 June 1994 at the Heights Bar

Yet families continue to push to know all they can, even though it will inevitably mean revelations that cause pain and reawaken grief.

The uncomfortable truths of policing and paramilitaries also have a danger of raising old divisions.

That is why Stormont is being pushed to find some sort of process that is able to deal with the long legacy of hurt.

Too often, what happened during decades of chaos in Northern Ireland is referred to, all too simply, as 'the past'.

However, properly addressing the many issues surrounding that past is anything but simple.

- Published9 June 2016

- Published9 June 2016

- Published9 June 2016

- Published9 June 2016

- Published9 June 2016