A small Belfast house is home to treasured war memories

- Published

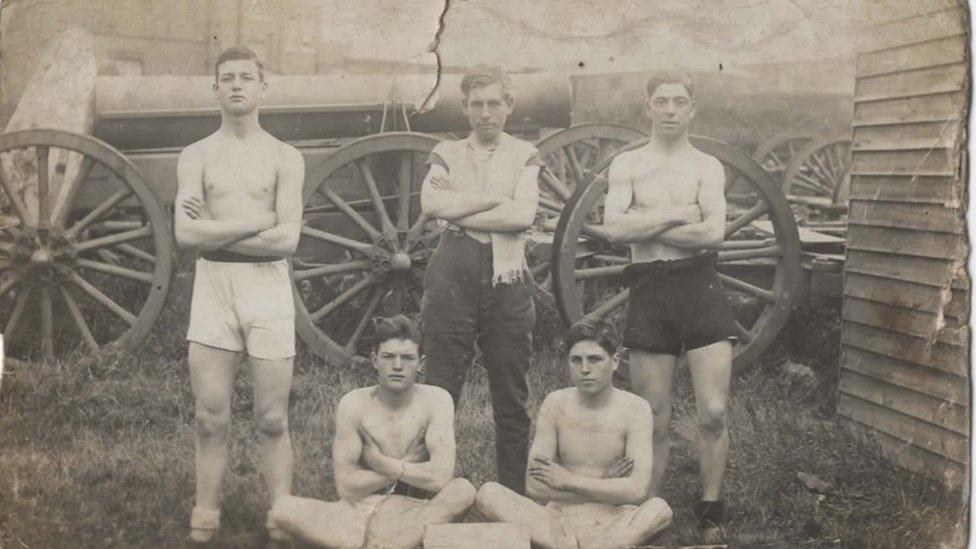

Harry Robinson taking part in Army sports is in the back row on the right

Every family has a history and most families have a link to World War One, if you look hard enough.

Friday marks 100 years since the Battle of the Somme.

It is a time when people dig out old photographs of fathers, sons and brothers who never came home or came home and were never the same.

Or they reach for medals stowed safely away wrapped in silk or linen or cotton wool, 100 years ago.

My grandparents' Belfast home was a small brick terrace house with an outside loo.

But its front parlour contained a fascinating cabinet of curiosities.

In among the china, the crystal glasses and the silver apostle spoons was hidden a bottle filled with tiny Australian snakes, a glass bell that allegedly contained "the sands of all the deserts of the world", and a tatty little book with the words: "Bible found on the battlefield".

The Bible is inscribed: "To Willie from Father and Mother 29/9/15".

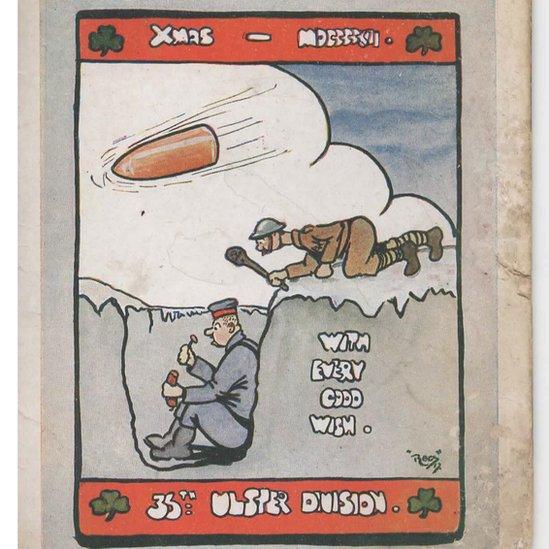

An old Christmas postcard celebrating the 36th Ulster Division

Who Willie was and whether he lived or died in battle, we will never know, but the Bible serves as a link to the Robinsons - my grandmother's father and brothers who went off to war.

Great-grandfather Willie-John Robinson was a remarkable 45 years old when he joined up.

He was a moustachioed veteran of the Belfast Fire Brigade, who lived in a flat in Chichester Street fire station with his wife, Sarah, and their 12 children.

Willie-John's son, Harry, was just 16 when he ran away to join the Army.

The records show he lied about his age, claiming he was a 19-year-old labourer when he was, in fact, an apprentice at the Workman and Clark shipyard.

Willie-John and his two older sons, Alec and Bill, served with the 36th Ulster Division on the Western Front.

A different fate awaited Harry.

Harry's brother, Alec Robinson, as an Army bugler

He joined the 6th Royal Irish Rifles, a mixed bunch of lads, Protestant and Catholic, from different parts of Ireland, part of the ill-fated 10th Division.

In a letter home from the Royal Barracks in Dublin written in a childish hand, Harry says he has been fined six days' pay for trying to attend a football match without permission.

"I have to do an hour's pack drill every night with about a stone on my back, and answer my name every half hour," he writes

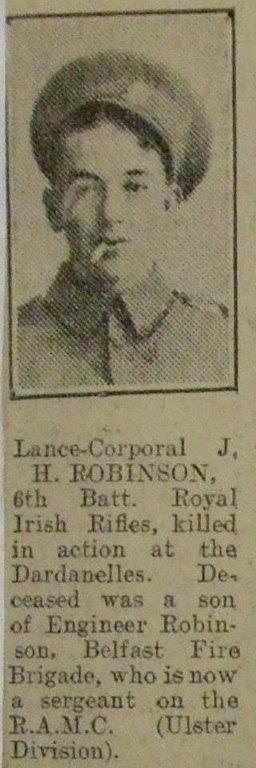

Harry Robinson's obituary: He was a 'cheeky chappy with a ciggie'

"I tell you this is not pleasant".

Harry's unit had never heard a shot fired in anger when they were sent to fight at Gallipoli in the summer of 1915.

His company was mown down on a patch of mountainside called "The Farm" on 11 August.

Harry's body was never recovered. He was 17 years old.

Back in Belfast, Sarah was distraught. Her son was dead, her husband was with the Army in England, and she had been left to look after nine children.

A letter from her brother to the War Office, dated 3 September, begs for details of Harry's death.

"His people are anxious," he writes.

We are left with a photo accompanying Harry's death notice in the Belfast Telegraph, a cheeky chappy in Army uniform with a ciggie hanging from the corner of his mouth.

Willie-John, now sergeant in the Medical Corps, and his other two sons were shipped to France.

They kept up a steady flow of postcards home.

A cartoon postcard addressed to my grandmother is signed: "From Dada, somewhere in France".

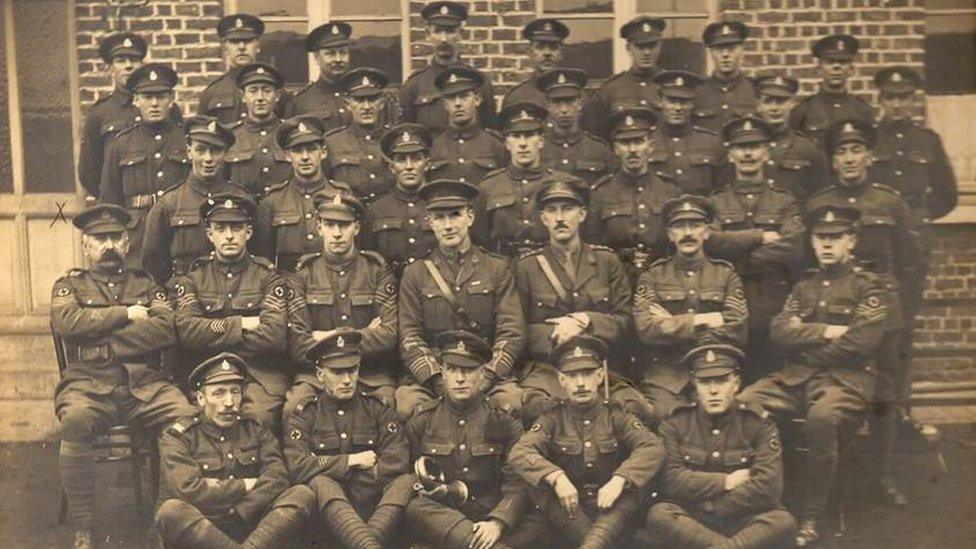

The final photograph shows Willie-John's unit at Mouscron on Armistice day 1918

A 36th Division Christmas card from 1917 shows a British Tommy about to bop a sausage-eating German over the head with a club.

The final photo in the family's war collection shows Willie-John's unit at Mouscron, a little village in Flanders where the Ulster Division was based when the Armistice came on 11 November 1918.

In the pump house tea rooms at the Titanic dry dock in Belfast, L/Cpl Harry Robinson's name is on the shipyard men's war memorial.

The families of Britain's war dead were issued with a scroll and a small plaque, known colloquially as the "Dead Man's Penny".

Harry was hardly a man. He was a 16-year-old boy when he ran away to fight a war.

Hundreds of thousands of mothers and wives and lovers faced the same heartbreak.

The penny was Sarah's link to her son who died thousands of miles away when he was still so young.

The years passed and there was another war.

All through her days, Sarah kept Harry's penny by the side of her bed - a talisman of a time long past and a boy who ran away.

The penny would remain there for the rest of her life until she, herself, died in 1950.