Between the sheets: Banned books censors didn't want you to read

- Published

Too hot to handle? A scene from Jed Mercuric's adaptation of the once banned book, Lady Chatterley's Lover, for the BBC in 2015

It is Book Week NI - a joint initiative between BBC Northern Ireland and Libraries NI that aims to celebrate the pleasures and benefits of reading.

But what of the books the authorities did not want us to enjoy? We look at the books they banned and the writers whose work was pulped, burned or decried from the pulpit.

Too damaging for young minds; too politically inflammatory or simply too sexy... these are the books they banned.

The greatest writers across the world often found their works stamped red by the censor.

For some readers, it made the illicit thrill of slipping between the sheets with Lady Chatterley's Lover or Molly Bloom even sweeter.

In the UK, D H Lawrence's tale of an adulterous affair was banned from 1928 until 1960, when Penguin won the right to publish after a famous court case.

At the trial, the prosecution asked: "Is this a book you would wish your wife or servants to read?"

The answer was resounding - On the first day of publication, 200,000 copies were sold - one up for Lady C., external

James Joyce's Ulysses - long considered one of the most important works of modern literature - was banned in the UK until the 1930s.

Across the globe, George Orwell's Animal Farm was not for sale in the USSR.

'Hot potato'

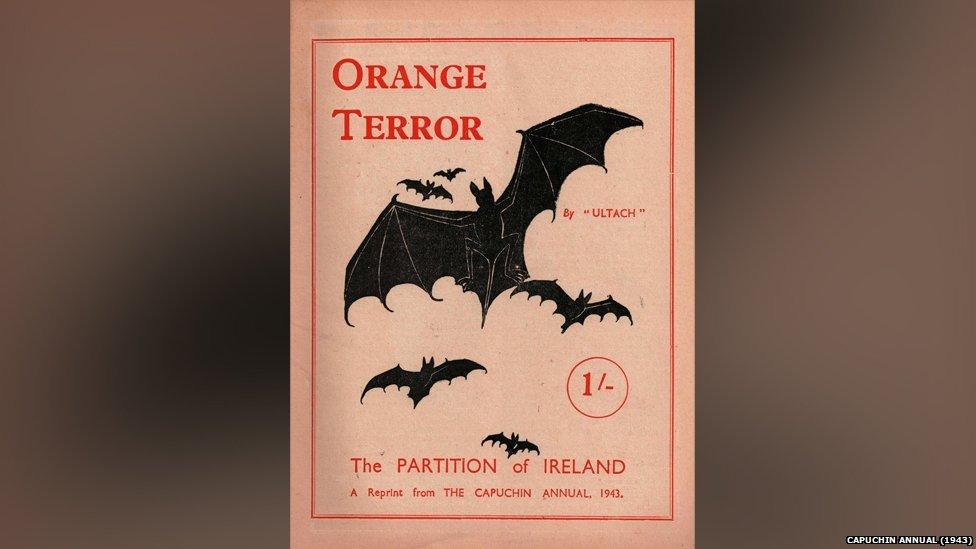

But in Northern Ireland, political pamphlets were more likely to catch the censor's eye at Stormont.

A few were banned under Northern Ireland's Special Powers Act.

Orange Terror: The Real Case Against Partition by Ultach (Ulsterman) was among them. Historian Dr Eamon Phoenix said the ban followed two days of debate at Stormont in January 1944.

The Orange Terror "sold like hot cakes" after it was banned

The writer begins his essay in the Capuchin Annual 1943 with the words: "I live there [in Northern Ireland]. Not only do I experience the effects of the persecution which is the dominant feature of life there but I know the people who vote for, support and benefit… from the continuance of the [Unionist] regime."

The writer had to remain anonymous. If the government had discovered who he was, he would have been imprisoned.

"That writer turned out to be educationalist J J Campbell," said Dr Phoenix.

"He was a working-class boy from north Belfast who grew up to gain a first class degree. He became a teacher at St Malachy's College in the city and was director of education at Queen's University in the 1970s.

"The Orange Terror was banned in January 1944, because it was considered to be 'prejudicial to peace and the maintenance of order'," he said.

"The nature of Ireland is that, given its ban, copies would sell like hot cakes - and they did," said Dr Phoenix.

If the Stormont government had found out who Ultach was, he would have been imprisoned, said Dr Phoenix

The irony, he pointed out, is that, in later years, Ultach - J J Campbell - would be one of three people appointed to sit on the Cameron Commission to address civil rights issues in Northern Ireland in the aftermath of the 1968 demonstrations and riots.

But if political pamphlets raised the temperature in Northern Ireland - in the Republic of Ireland, sex, religion and even a muttered profanity could do for a book.

'Evil Literature'

The first Irish censor, James Montgomery, famously said: "I know nothing about films, but I know the 10 commandments."

Following the creation of the new Irish state in the 1926, a Committee on Evil Literature was appointed.

When WB Yeats was awarded the Nobel prize for literature, the Catholic Bulletin denounced the prize as "the substantial sum provided by a deceased anti-Christian manufacturer of dynamite" and as the promotion of Paganism.

Copies of Joyce's Ulysses were never officially banned by Irish censors but were very hard to get hold of. It is said that they were smuggled into Ireland in boxes marked "sanitary towels".

Writers from Northern Ireland were among the hundreds who fell foul of those censors.

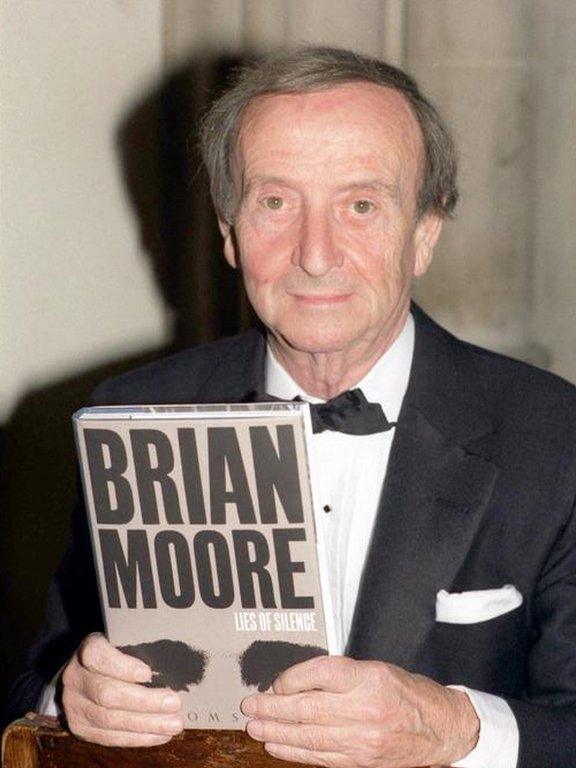

Brian Moore's youthful rejection coloured his novels

Belfast-born writer Brian Moore, Benedict Kiely from Dromore, County Tyrone and Sam Hanna Bell were "on the list" .

Moore was forever influenced by his loss of Catholic faith, external.

This rejection of Catholicism coloured his novels and some were banned by the Catholic Church.

Kiely had three of his novels banned under the Republic of Ireland's laws. In later years, he would remark: "If you weren't banned, it meant you were no bloody good".

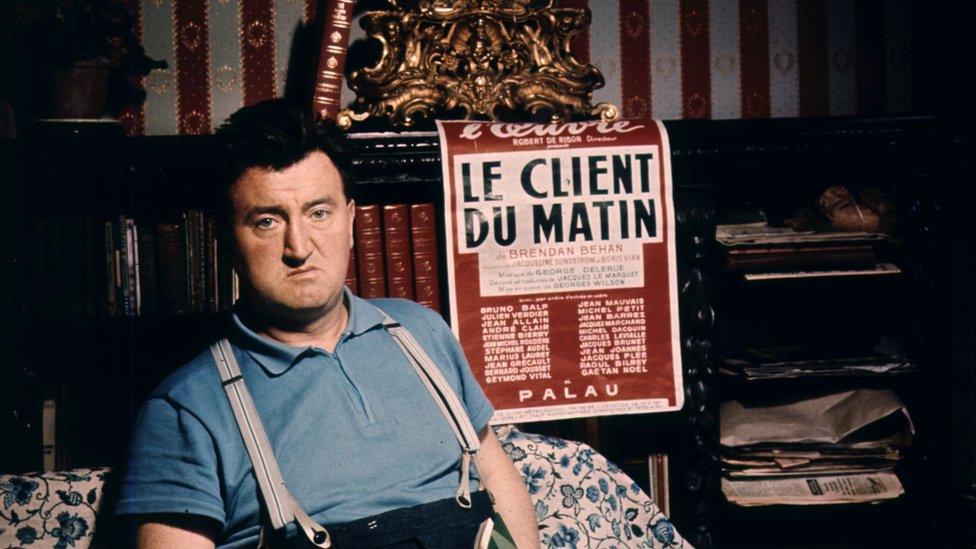

Kiely told the story of Irish republican and writer Brendan Behan whose autobiography, Borstal Boy, was banned in Ireland.

Brendan Behan took his revenge against the Irish censors in song

Behan was lamenting the ban in a pub when he was approached by a man who asked for a rough measurement of the book. He made a quick calculation and offered to bring 2,000 copies across the border into the Republic of Ireland from Northern Ireland - in lieu of his usual cargo of smuggled butter.

Behan took his revenge in humour. He wrote a song with the lyrics:

"My name is Brendan Behan, I'm the latest of the banned,

Although we're small in numbers we're the best banned in the land,

We're read at wakes an weddin's and in every parish hall,

And under library counters sure you'll have no trouble at all."

But for others, who went on to win acclaim on the international stage, Irish censorship hurt.

Irish writer Edna O'Brien burst on to the literary scene with The Country Girls in 1960 - a novel that described a young woman's awakening sexuality. The Irish censor was so appalled he banned it and the same fate awaited her next six novels.

A feature in the Guardian, external tells the story that four copies of that novel unaccountably turned up in a shop in Limerick.

'Social disgrace'

One was supposed to have induced a seizure in a woman reader. The other three were bought by O'Brien's parish priest who took them back to Tuamgraney where they were publicly burned.

Another writer who won acclaim, John McGahern, remembered being told that the prohibition of his childhood memoir, The Dark - banned for alleged obscenities in 1965 - was "great news" because of the publicity and sales it would generate.

"Odd enough, that's not the way I felt because, in that sense, one has a family in Ireland, and it was quite a social disgrace," he said.

McGahern lost his teaching job in Dublin because of the book - "The order for my dismissal came from the archbishop," he said. He could not write for three or four years after "the business".

Irish writer Edna O'Brien has had a fraught relationship with Ireland

But as the Chatterley trial signalled changed times in the UK , in Ireland, the McGahern affair played a similar role. By 1967, the slow dismantling of the censorship system had begun.

Of course there are books that are still beyond the pale.

In the Republic of Ireland, one such banned tome, external is: How to Drive Your Man Wild in Bed.

Sometimes, it seems, you just have to use your imagination.

- Published2 February 2013

- Published7 April 2016

- Published10 September 2015

- Published27 September 2010