Bengoa Report Q&A: Background to latest shake-up of NI health services

- Published

Previous reports that recommended closing hospital emergency departments proved too bitter a pill to swallow for Stormont politicians

A long-awaited report on the future of Northern Ireland's health and social care system has been published.

The Bengoa Report was commissioned by NI ministers seeking advice on how to improve services, cut waiting lists and care for an ageing population.

Written by experts, led by Prof Rafael Bengoa, it is expected to recommend widespread change and tough decisions.

It follows three previous major reviews that each recommended closing several hospital emergency departments.

Harsh medicine, but the earlier reports argued that resources and expertise were too thinly spread across too many locations.

However, closing hospitals is highly emotive and unpopular and so far, the pill has been too bitter for politicians to swallow.

Q: Why does Northern Ireland need health and social care reform?

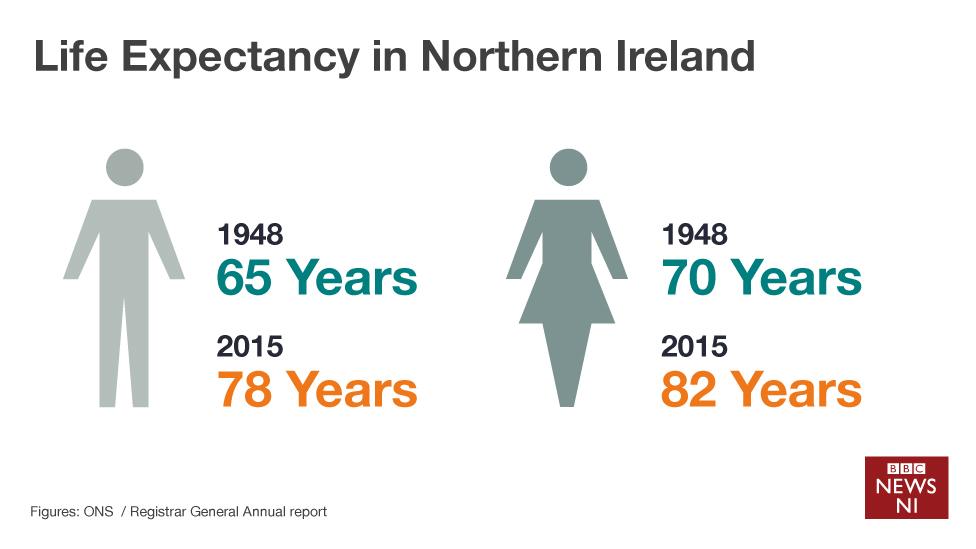

Like the rest of the UK, people in Northern Ireland are now generally living longer than was the case in previous generations.

When the UK's National Health Service was set up in 1948, the average life expectancy in Northern Ireland was 65 for men and 70 for women.

In 2016, the average life expectancy of a man in Northern Ireland has risen to 78, while for a woman it is now 82 years.

The change is due, in part, to improved treatments for life-threatening conditions like cancer and heart disease.

Higher life-expectancy is a positive development, but it also means that there are more elderly people to look after, relative to the size of the working population.

As we live longer into old age, more patients are coping with chronic and complex medical conditions which can require years of treatment and support.

There are also lifestyle factors to consider which affect all age groups - eating too much, drinking too much alcohol and smoking are all putting pressure on health services.

So living longer does not necessarily mean we are living healthier lives.

Q: Is this the first time these problems have been tackled?

The Bengoa Report is not the first prescription politicians have sought for the ailments facing Northern Ireland's health care services.

Since the turn of the century, three major reviews have been published and each suggested cutting the number of acute hospitals - those providing A&E services and emergency surgery.

In 2001 - The Maurice Hayes Review recommended the removal of accident and emergency services, external from five of Northern Ireland's smallest acute hospitals, building a new acute hospital in County Fermanagh and a significant reduction in bureaucracy by merging health boards and hospital trusts.

In 2011 - The Compton Report, external, made 99 recommendations, including halving the number of acute hospitals from 10 to five. It also said £83m should taken out of hospital services and put into community care, so patients and elderly people could stay in their own homes for as long as possible.

In 2014 - The Donaldson Review, externalclaimed there were too many hospitals in Northern Ireland. It argued that elsewhere in the UK, a population of 1.8m people would likely be served by four acute hospitals. It said patient safety was at risk, because of inconsistencies between peak and off-peak services.

Sir Liam's report recommended setting up an international panel of experts to redesign some health and social care facilities.

In January 2016, Stormont's then health minister Simon Hamilton agreed and appointed a panel of six, chaired by Prof Rafael Bengoa.

Q: Who is Prof Rafael Bengoa?

Prof Bengoa chairs the panel for Northern Ireland health care reform

The Spaniard is an internationally renowned expert on health reform who has advised the European Union and the Obama administration in the US.

He worked for the World Health Organisation (WHO) for more than 15 years.

He is also a former minister of health in the Basque region.

Q: How much strain are waiting lists under?

This time last year, a senior health expert said heads would roll in England if hospital waiting lists were as long as those in Northern Ireland.

In an interview with the BBC in October 2015, Nigel Edwards, chief executive of the Nuffield Trust, described the figures as "serious" and called for immediate action.

Between 2014 and 2015, there was almost a 50% rise in waiting lists.

The numbers jumped from 155,558 patients in September 2014 to 230, 625 in September 2015.

According to the most recently published data from August 2016, more than 225,000 men and women were on a waiting list to see a health consultant.

More than 70,000 were waiting for in-patient and day patient appointments.

More than 95,000 were in a queue for a diagnostic service.

Q: What is the current state of emergency care provision?

Northern Ireland has nine acute hospitals that are open round the clock. Two others have reduced opening hours for their emergency departments.

Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast - home of Northern Ireland's regional trauma centre.

Mater Hospital, Belfast - 24-hour emergency department

Altnagelvin Hospital, Londonderry - 24-hour emergency department

Antrim Area Hospital - 24-hour emergency department

Causeway Hospital, Coleraine - 24-hour emergency department

Craigavon Area Hospital - 24-hour emergency department

Daisy Hill Hospital, Newry - 24-hour emergency department

South West Acute Hospital, Enniskillen - 24-hour emergency department

Ulster Hospital, Dundonald - 24-hour emergency department

Lagan Valley Hospital, Lisburn - type two emergency department open week days only from 08:00 to 20:00

Downe Hospital, Downpatrick - type two emergency department open week days only from 08:00 to 20:00

Q: What is the future prognosis?

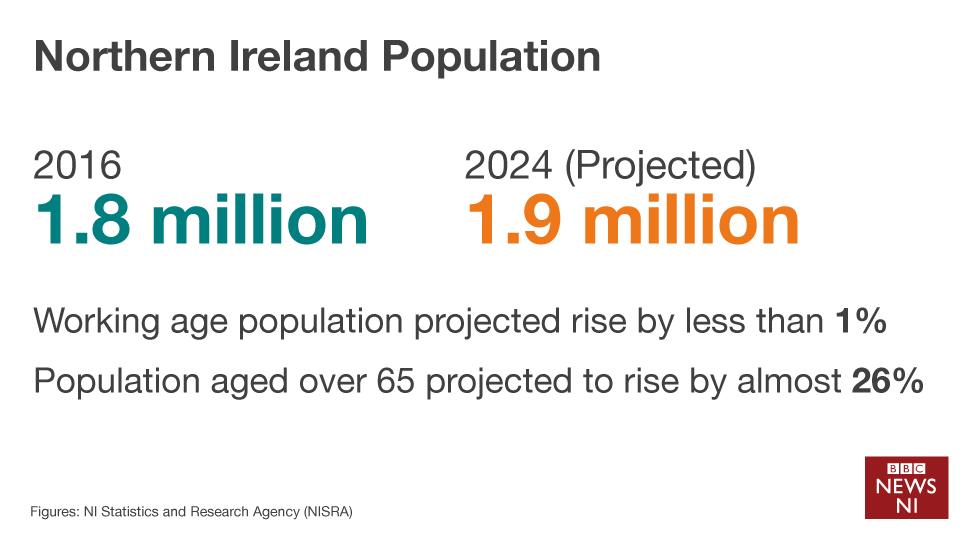

The challenges posed by an ageing population are likely to be exacerbated in the coming years, unless the problems are addressed.

The number of people aged over 65 is due to rise by almost 26%

By the year 2024, Northern Ireland's 1.8m population is expected to rise by more than 5% to just under 2m.

The number of people aged over 65 is due to rise by almost 26%, while the working age population is set to rise by just 1%.

The wide-ranging demands placed on the health service are also increasingly costly and complex.

Last year, more than 6,000 people turned up at emergency departments across Northern Ireland having self-harmed - most were aged between 15 and 24.

Over-indulgence on food is leading to increased levels of diabetes and weight-related disorders, while the abuse of alcohol and drugs are putting a strain on emergency departments.

When he published his report into Northern Ireland's health care system last year, England's former chief medical officer, Sir Liam Donaldson, said acute hospitals were being "kept in place because of public and political pressure".

Since then, Stormont ministers have been making noises that suggest they are preparing to take some unpopular decisions.

This month, Health Minister Michelle O'Neill called the current waiting list figures "shocking" and "unacceptable".

Her predecessor Simon Hamilton talked about the need for consensus and taking the "politics out of healthcare".

Whether ministers will follow doctors' advice this time remains to be seen.

- Published17 February 2016

- Published7 January 2016