Post-natal depression: Speaking out about 'secret stigma'

- Published

An estimated 10-15% of mothers in the UK develop post-natal depression

It has been 17 years, but Belfast mother-of-four Samantha Patterson still remembers the secret stigma of post-natal depression.

"I hid it from my friends, if I was really bad I just didn't go out," she said.

"If I'd had someone to talk to like me, who'd been through it, I think I would've come through it quicker."

She was diagnosed with the illness following the birth of her second child, but it is only now for the first time that she feels able to talk about it openly.

"I had members of my family saying: 'You'll shake out of it.' And it was the most unhelpful thing, as if it was my fault," she told the BBC.

"I didn't feel like I had anyone to talk to about it."

Samantha is not alone.

'Baby blues'

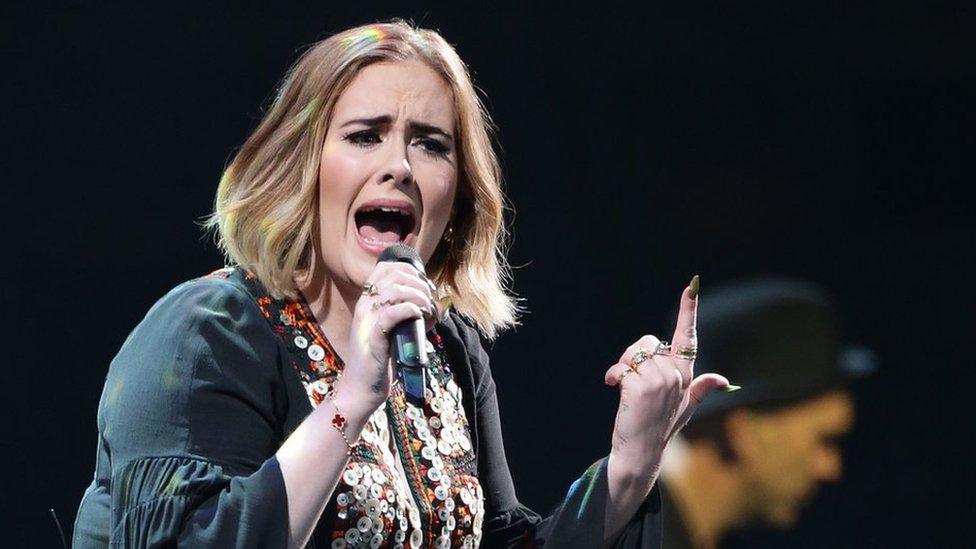

Post-natal mental illness affects around one in 10 mothers in the UK and has been back in the headlines recently since singer Adele revealed she suffered from it after the birth of her son, Angelo.

Adele told Vanity Fair magazine she really struggled adjusting to motherhood

Many women usually experience so-called baby blues in the first week after a new baby is born.

They can feel tearful, exhausted and anxious about how they are going to cope, but these feelings usually don't last for long.

'Moments of rage'

Samantha Patterson knew that what she was experiencing after the birth of her second child was much more serious than that.

"Whenever I had baby blues, I would've been crying but I was happy too," Mrs Patterson told BBC News NI.

"With post-natal depression, I felt like I couldn't cope.

"I was suffering so much, I had a toddler as well in the house and I didn't want to be near her, I didn't want to be near anybody.

"Part of me forced myself to cuddle my baby, I didn't want to."

She described experiencing a rollercoaster of emotions from one minute to the next.

"I went through moments of rage, where I was really angry at everyone - and angry with myself for having post-natal depression," said Mrs Patterson.

"I spent days lying on the floor crying and sitting in bed, I just couldn't face doing anything.

"I could've done with somebody like me, saying to me that they've been through it and there is a light at the end of the tunnel."

Symptoms of post-natal depression

Persistent feeling of sadness

Loss of interest in the wider world

Feeling tired all the time

Difficulty bonding with your baby

Withdrawing from contact with other people

Problems concentrating and making decisions

Frightening thoughts - for example, about hurting your baby

While midwives and health visitors in Northern Ireland are now being trained to recognise the signs of post-natal depression, Breedagh Hughes from the Royal College of Midwives said it was still very much a "taboo" topic.

"There is this societal expectation that when a woman gives birth she should be happy, jolly and delighted with herself," said Ms Hughes.

"In fact, women who suffer from post-natal depression then try to compensate by trying to be a perfect mother, but emotionally there is nothing there."

No mother-and-baby units

Ms Hughes said she supported celebrities like Adele speaking out about their experience with the illness, adding that their contribution helped to normalise a topic that is still too painful and awkward for many people to broach.

She told BBC News NI: "It is great when high-profile people can say: 'Look, it happened to me - you're not alone.'

"But there also need to be people who will put their hands up, women who stand up and say: 'Here's what helped me.'"

About 70 women a year in Northern Ireland require hospital admission after being diagnosed with the illness.

But during treatment, as there is no mother-and-baby unit, the woman is separated from her baby.

In England and Scotland, there are 17 specialist units.

There have been calls for perinatal services in Northern Ireland to be radically overhauled

The Royal College of Midwives hopes that a specialist perinatal unit for women in Northern Ireland could soon become a reality.

Last week, Health Minister Michelle O'Neill published her action plan to radically reform Northern Ireland's health and social care system.

She has since expressed an interest in exploring the establishment of an all-island perinatal centre, as there is no specialist service in the Republic of Ireland either.

Services required included perinatal mental health and inpatient services for mothers, a department spokeswoman told BBC News NI.

"The Minister is therefore considering options to establish specialist community-based perinatal mental health services in every Trust area, and to establish a regional Mother and Baby Unit," said the spokeswoman.

But she added that no decisions had been made as yet, and issues of funding, service planning and prioritisation still needed to be addressed.

Ms Hughes said she believed there was a "great political will" to see such a unit set up.

"If families hear that their wife or daughter is going to be admitted to the very best place, they can have their baby with them, 24-hour care, I don't think families would mind travelling to get that," she told BBC News NI.

Scars of mental illness

Samantha Patterson has since had two more children, and said she feels lucky that she did not experience post-natal depression during either of those pregnancies.

But the scars of dealing with the mental illness are still evident.

"Until you've been through it, you don't know how dreadful it is," Mrs Patterson said.

"At the time, all that kept me going was that I had to get better for my kids - but talking about it now, it's definitely helpful."

- Published1 November 2016

- Published1 March 2016

- Published24 February 2016

- Published6 July 2011

1.jpg)