Black hole 'swallowed star', say Queen's astronomers

- Published

QUB researchers believe the Sun-like star wandered too close to a "supermassive" black hole and was "ripped apart"

Belfast-based astronomers have helped to discover a very rare celestial event - a star being "swallowed" after it passed too close to a black hole.

Queen's University, Belfast, (QUB) was involved in a European project to solve the mystery of an "extraordinarily brilliant" light in a distant galaxy.

Last year, US scientists assumed that the light came from an exploding star.

But after studying it for 10 months, QUB astronomers believe the star was ripped apart by a spinning black hole.

'Supermassive'

Black holes are regions of space where gravity is so powerful that even light cannot escape.

The largest type of black hole is referred to as "supermassive" and the one under examination is believed to have a mass of "at least 100m times that of the sun", according to QUB.

The team from QUB's Astrophysics Research Centre was involved in gathering months of data from a selection of telescopes, both on earth and in space, including the Hubble space telescope.

The light source, named ASASSN-15lh, was initially categorised in the US in 2015 as the brightest supernova (exploding star) ever seen.

However, QUB Professor Stephen Smartt, said: "We observed it and thought: 'Nah, it doesn't look like a supernova to us.'"

Prof Smartt is the leader and principal investigator of the European Southern Observatory (ESO) project, based in Chile.

"We've a big group at Queen's," he told BBC Radio Ulster's Evening Extra programme.

"We work in the School of Maths and Physics at Queen's and our speciality is looking for things that move - like asteroids that might hit the earth, or things that flash, which might be supernova or these black holes."

He said the light "puzzled us for months" but based on their telescopic observations, the QUB team proposed a new explanation for the object in a galaxy far, far away.

It believes the sun-like star wandered too close to the black hole and was "ripped apart", a phenomenon known in astronomy as a "tidal disruption event".

In the process, the star was "spaghettified and some of the material was converted into huge amounts of radiated light," said a QUB statement.

"This gave the event the appearance of a very bright supernova explosion, even though the star would not have become a supernova on its own as it did not have enough mass."

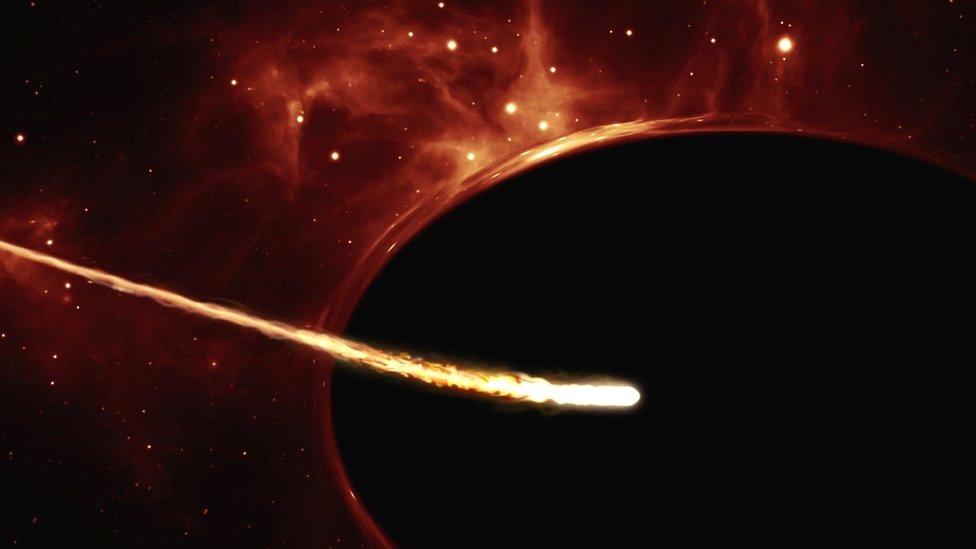

An artist’s impression depicting a rapidly spinning supermassive black hole surrounded by a disc of rotating material consisting of the leftovers of the destroyed star

Prof Smart told Evening Extra that a black hole was the "densest form of matter we know".

"If you could take every person on earth and squeeze them on to a teaspoon - that would be the density of a neutron star, or neutron star material, and a black hole is probably 10 times denser than that.

"So it's an object from which light cannot escape, it's an object that is denser than any known matter that we can see or test in the universe."

He said the formation of black holes was still a mystery.

"We think they formed in the very early universe, as galaxies started forming, and there's quite a lot of evidence for that," he said.

"For example, our own Milky Way galaxy has got a massive black hole which is about one million times the mass of the Sun, and we known that because we can see stars going round and we can measure their velocities, so we know the mass must be there."

Prof Smartt paid tribute to Dr Giorgos Leloudas, from Israel's Weizmann Institute of Science, who published the research on Monday in Nature Astronomy.

"Our results indicate that the event was probably caused by a rapidly spinning supermassive black hole as it destroyed a low-mass star," said Dr Leloudas.

To date, this type of event has only been observed about 10 times, but Dr Leloudas added a note of caution on the findings.

"Even with all the collected data we cannot say with 100% certainty that the ASASSN-15lh event was a tidal disruption event, but it is by far the most likely explanation."