HIA report set to bring painful chapter in NI's history to a close

- Published

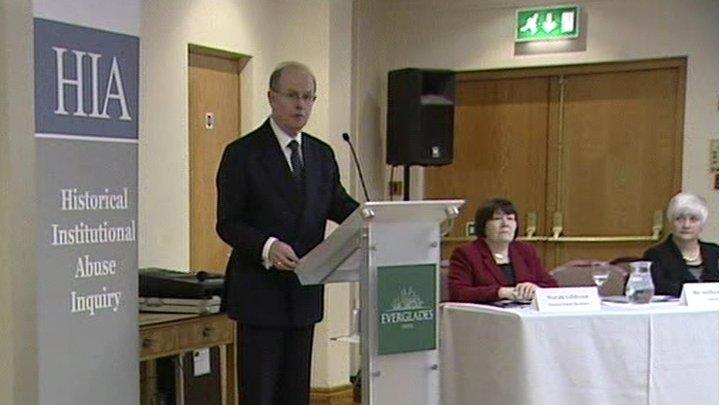

The Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry heard evidence at Banbridge Courthouse from 2014 to 2016

The Historical Institutional Abuse (HIA) Inquiry exposed deep wounds in the hearts and lives of hundreds of people who went through the childcare system in Northern Ireland in the last century.

Its investigations focused on residential homes and institutions operated by the state, churches, and the charity Barnardo's.

There were many reasons why children of that era found themselves in residential care in Northern Ireland.

Many were orphaned, some were abandoned or living in extreme poverty.

Others came from dysfunctional family settings and were victims of violence, abuse or neglect in their own homes.

Some were in the juvenile justice system, while many were born to unmarried mothers.

The latter was a matter of great public shame at that time, especially in the eyes of an austere, sometimes harsh and dominant Catholic Church on both sides of the Irish border.

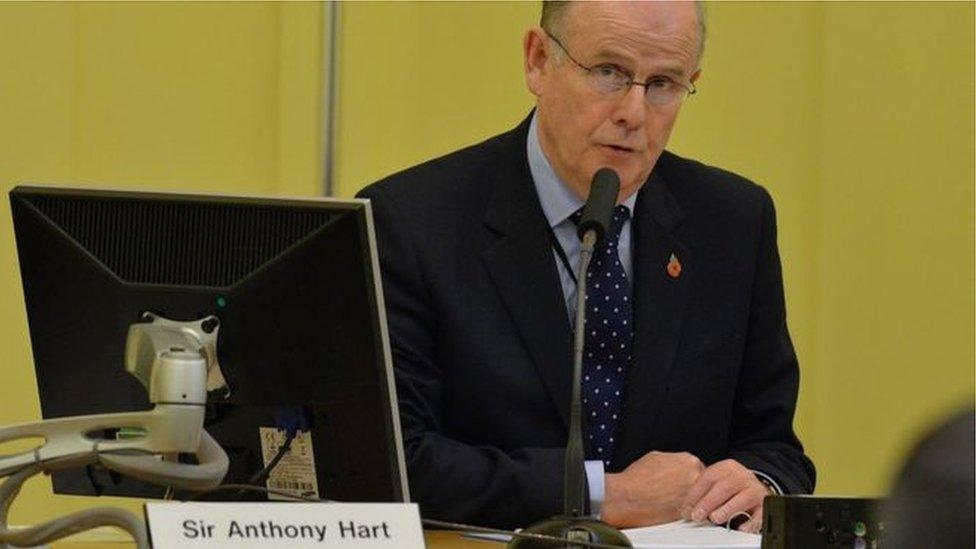

The HIA was led by retired judge Sir Anthony Hart

Whatever their reasons for being in care, the system let countless children down.

The public hearings, over two-and-a-half years, bore witness to accounts of grim and sometimes gruesome abuse, cruelty and neglect.

The sexual, physical and emotional abuse was perpetrated by individual men and women working in the homes and institutions.

It was also inflicted by visitors and, in many cases, children inflicted sexual, physical and emotional abuse on each other while in care.

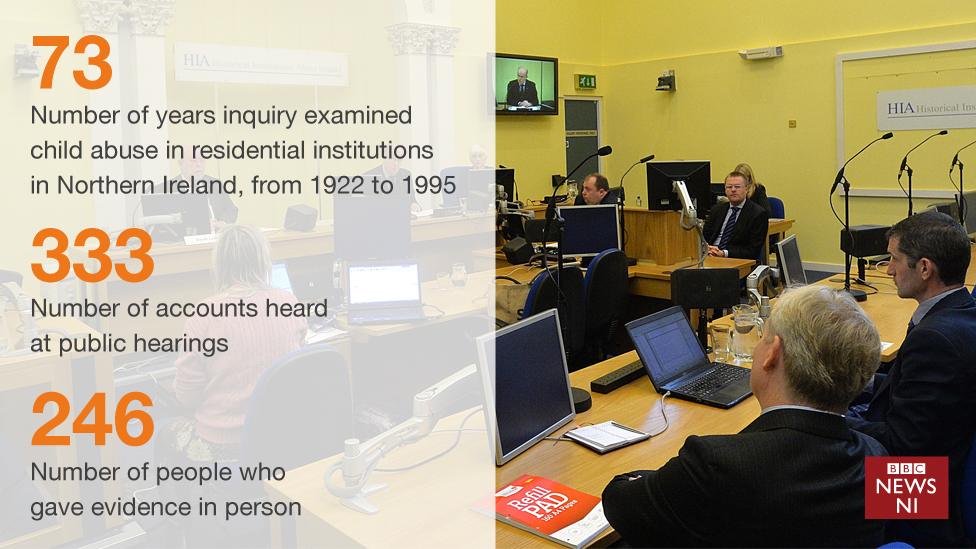

Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry: In numbers

2010: HIA Inquiry first announced

73: Number of years inquiry examined child abuse in residential institutions in Northern Ireland, from 1922 to 1995

2014: Inquiry first begins hearing public evidence on 14 January. At the time, it's the biggest inquiry into child abuse ever in the UK

434: Number of people who made formal applications to speak to inquiry before 2014

333: Number of accounts heard at public hearings

246: Number of people who gave evidence in person

87: Statements submitted into the public record

29: Minimum number of victims thought to have been abused at Kincora Boys' Home in east Belfast, that was investigated as part of the inquiry

2016: Public evidence ends in July last year

The accounts of 333 people were heard at the public hearings - 246 gave evidence in person and a further 87 statements were read into the record.

The statements were recorded because the former residents in question were often too unwell to attend.

Poignantly, in some cases, the former residents had died before getting the chance to tell the inquiry about what happened to them as children.

The spectre of middle-aged or elderly former child residents taking the witness stand at the inquiry was a chastening experience.

Sometimes frail, often traumatised, their individual accounts were very different. Yet, there was a constant narrative of early-age suffering and lifelong pain and anguish.

The inquiry often heard accounts of children separated from the parents and siblings at an early age

Many of the accounts of sex abuse and beatings were staggering in terms of the vile and brutal nature of what happened to the children.

The repeated evidence painted an image of a harrowing, dark and bleak period of childcare in Northern Ireland, from 1922 to 1995.

Countless children living loveless, lonely lives in frightening environments.

In many cases, separated from their parents at an early age, and separated from their siblings in care.

Despite lifetimes spent searching, some brothers and sisters were never reunited with each other or with their parents.

Vulnerable children

Those who came forward to give evidence blamed many people for their damaged childhoods.

Some blamed their own parents for abandoning them in the first place, most blamed the people working in the state, church and Barnardo's' institutions.

Others held the Stormont government of the time, welfare agencies, and wider society to account, for turning a blind eye to the needs and welfare of vulnerable children in care.

Even though the inquiry was specifically designed to examine child abuse in the homes and institutions, some former residents came forward to defend some Catholic residential homes being investigated.

Three senior care staff at Kincora were jailed in 1981 for abusing 11 boys

These witnesses paid tribute to nuns and Christian Brothers who cared for thousands of deprived children and praised these institutions for giving them a chance in life.

Another aspect of the public hearings which provided more troubling testimony was the investigation into a Child Migrant Scheme, operated by the British government, which sent children from across the UK to Australia in the middle of the 1900s., external

'Substandard children'

From Northern Ireland, 131 children, some as young as five, were sent to Australia from Catholic, Protestant and local authority childcare homes.

The experiences of 50 of them were heard by the inquiry, mostly via a videolink.

Most recalled being promised a better and happier life in Australia. However, many said they endured further hardship and abuse during their new lives on the other side of the world

The inquiry was also told that the Australian government wanted children who were "white and of good health".

In a letter, sent in 1947, it complained to the authorities in Northern Ireland of being sent "substandard children" and introduced an IQ test to the scheme.

The accounts of these migrant children, and the children who remained in local homes and institutions, have now been recorded in the official history of Northern Ireland.

It's a record that speaks to a dark and unforgiving period in the care and treatment of vulnerable children and young people.

- Published13 January 2014

- Published31 May 2016