Irish language act a necessity, says Council of Europe

- Published

- comments

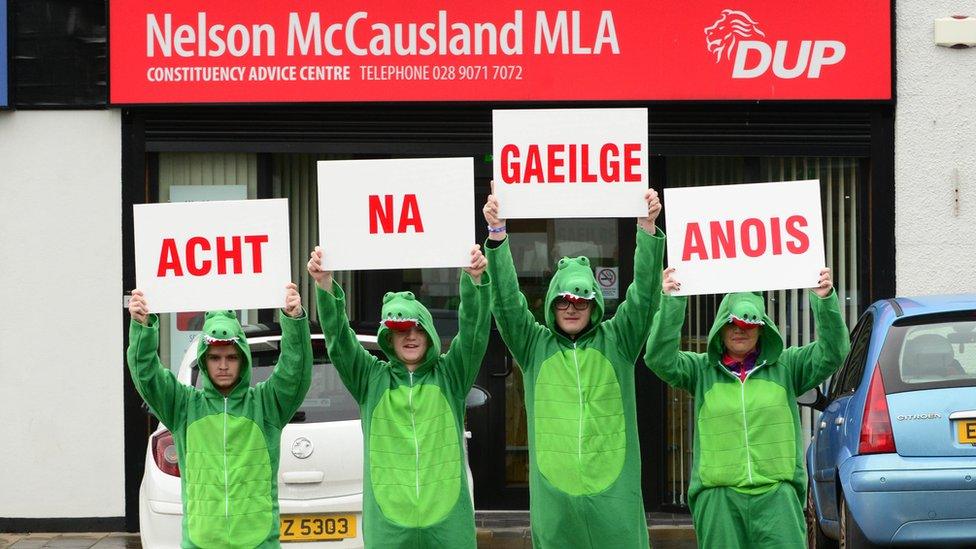

An Irish language act was a key campaigning issue ahead of last week's Assembly election

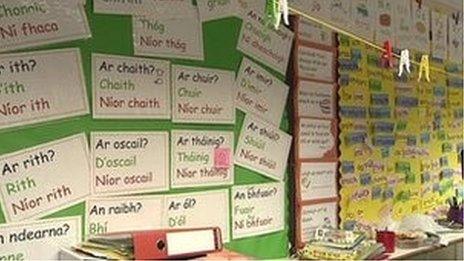

An Irish language act in Northern Ireland is a necessity that is being prevented by "sectarian politics", says a human rights body.

A new Council of Europe (CoE) report is critical of how Stormont promotes the Irish language.

The report also calls for the government to encourage the Executive to introduce language legislation.

The council is a human rights organisation founded in 1949 with 47 member states.

Sinn Féin MLA Carál Ní Chuilín said the report highlighted the British Government's shortcomings on issues of legislation, strategy and provision after it had committed to bring forward an Irish Language Act.

"If the current political talks are to have any value then agreements need to be implemented," she said.

No information from Executive

The criticism is contained in the CoE's fourth report on how the UK is complying with its convention for the protection of national minorities.

"The apparent gridlock in the Irish power-sharing arrangement has prevented adoption of the Irish language bill," it says.

"The lack of progress on language rights of persons belonging to a national minority is emblematic of a wider practice of sectarian-driven policy making that appears to dominate the political process."

As a result, the report calls the Irish language a "hostage of sectarianism".

The DUP's Nelson McCausland said there must be "equality" over language issues.

"This report covers both Ulster Scots and Irish language but a lot of the focus as been on one part of the report and the other part has been almost completely ignored," he said.

"We have a number of different political and cultural perspectives. If Northern Ireland is to work, all of them need to be respected and unfortunately, I would suggest, people in the unionist community feel they are being treated as second class citizens".

The council is a human rights organisation founded in 1949 with 47 member states

The Executive failed to provide the council with information on their approach to minority issues, because they could not agree a submission.

"This is the consequence of the lack of agreement on minority and human-rights related issues between the two largest parties of the executive," says the report.

Instead, the report is based on information from the UK government and a range of non-governmental organisations.

However the CoE also questions the UK government's role in facilitating language legislation, saying opposition from unionists could "be bypassed if the UK government used its parallel legislative competence".

It subsequently calls on the "UK government to help create the political consensus needed for the adoption" of an Irish language act.

The council is also critical of the failure to introduce a strategy for Ulster-Scots language, heritage and culture.

Additionally, the CoE report criticises aspects of the executive's 'Together Building a United Community' (TBUC) strategy.

Minorities increasing

It says that "good relations" could be used as an excuse "to set aside politically contentious issues, such as legislating on the Irish language, and to justify a 'do nothing' attitude".

It also accuses the executive of not doing enough to cater for the needs of ethnic minorities here.

"While the number of other, numerically smaller minorities has increased over the last decade in Northern Ireland, the executive has not been addressing the rights of these newcomers," says the report.

It calls for stronger racial equality rights and legislation, and criticises the authorities for failing to collect accurate data about ethnic minorities including travellers, gypsies and Roma.

Talking shop?

The council's framework convention for the protection of national minorities was signed by the UK in 1995 and sets out a number of principals to be respected by states to protect minorities.

But the CoE cannot force the UK government or the Northern Ireland Executive to implement its recommendations.

That has previously led some critics to accuse the council of being a talking shop with little power, other than diplomatic pressure.

- Published7 February 2017

- Published17 February 2014

- Published12 April 2014