Article 50: The view from Northern Ireland

- Published

Northern Ireland's unique Brexit challenge is the Irish border.

The main Stormont parties, the Irish government and business groups across the island want border arrangements to remain as close as possible to the status quo. Currently people and goods can pass unimpeded across that 500km border.

The movement of people is governed by the Common Travel Area, external (CTA). It's an arrangement which has existed since 1922 and allows for free movement between Ireland, Northern Ireland the rest of the UK.

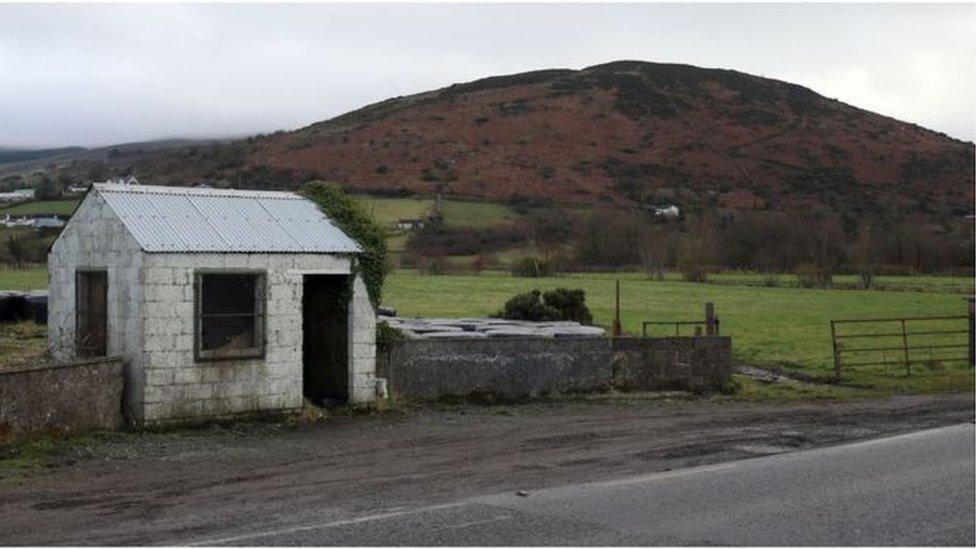

The remains of the old border point separating Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland

It also allows Irish and UK citizens to access various services and benefits in each country such as the right to work, to access public services and to vote in certain elections. It also means there is a large degree of co-operation on immigration controls.

It is a bi-lateral arrangement between Ireland and the UK, which means it should be reasonably straightforward to sort out. Brexit Secretary David Davis has described the continuation of the CTA as "non-negotiable" and the Irish government have it as one of its Brexit priorities.

The main complication could be around any new migration controls the UK imposes on EU citizens.

Irish Taoiseach Enda Kenny (l) there is "a political agreement" between the British and Irish government that there will no customs posts

The top official at Ireland's Department of Justice has said that Ireland cannot be expected to use its migration system to prevent non-Irish EU citizens using the CTA to travel to the UK. "We're not going to interfere with the rights of free movement of EU nationals, that's simply not going to happen," he told a parliamentary committee.

There are greater complications around what happens to the free movement of goods when the UK leaves the EU customs union.

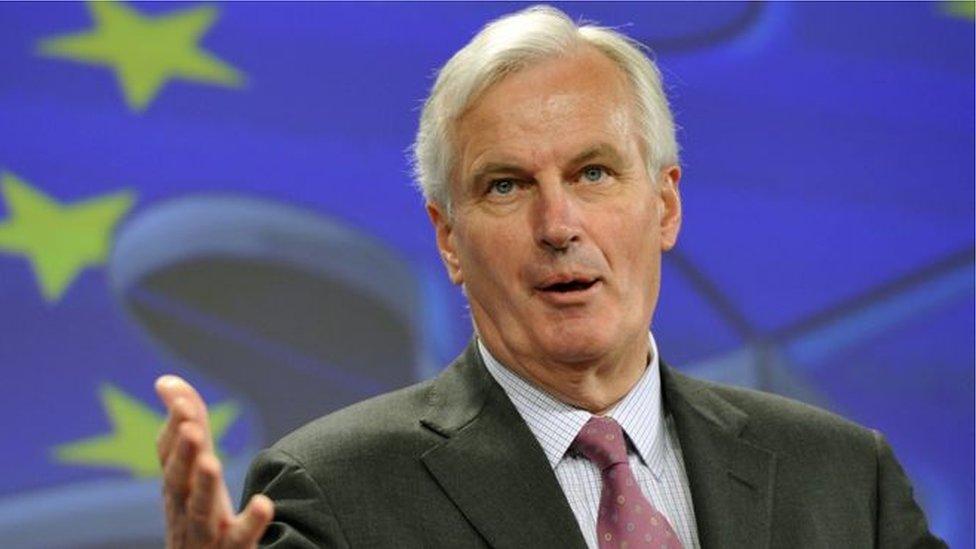

David Davis and the EU's chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, agree there should be no return to a hard border, meaning a border which has physical form, through checkpoints or customs posts.

Northern Ireland, like Scotland, voted Remain in the referendum

From 1923 until the creation of the EU Single Market in 1993, there were customs posts at points on the border. David Davis has said the British government has no intention of rebuilding those posts.

The Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Enda Kenny added that there is "a political agreement" between the British and Irish government that there will no customs posts. But after Brexit the Irish border becomes an EU frontier and what happens there is an issue for the EU as whole, not just the Irish government.

There are concerns on both sides of the border over the possible effects of Brexit

The EU's Mr Barnier, says he will be "particularly attentive... to the consequences of the UK's decision to leave the customs union, and to anything that may, in one way or another, weaken dialogue and peace."

So the main players all share the will to prevent a hard border but the caveats in their language suggest they have not yet found a way.

Michel Barnier says he will be "particularly attentive... to anything that could weaken dialogue and peace" in Northern Ireland.

Much of the speculation has centred on a virtual border where all declarations are made electronically and freight movements are monitored by number plate recognition technology. The Sweden/Norway border is suggested as a model. However, there are still physical customs posts on that border, so the Irish solution would need to go beyond what has been achieved there.

This will have to be resolved sooner rather than later, because Mr Barnier said it is one of three issues which needs to be settled before talks on a trade deal and the future UK/EU relationship can start.

- Published28 March 2017

- Published20 March 2017

- Published22 March 2017

- Published17 November 2016