Brendan Duddy obituary: NI's 'secret peacemaker'

- Published

Beef burgers were delivered to Brendan Duddy's family fish and chip shop by a young van driver called Martin McGuinness

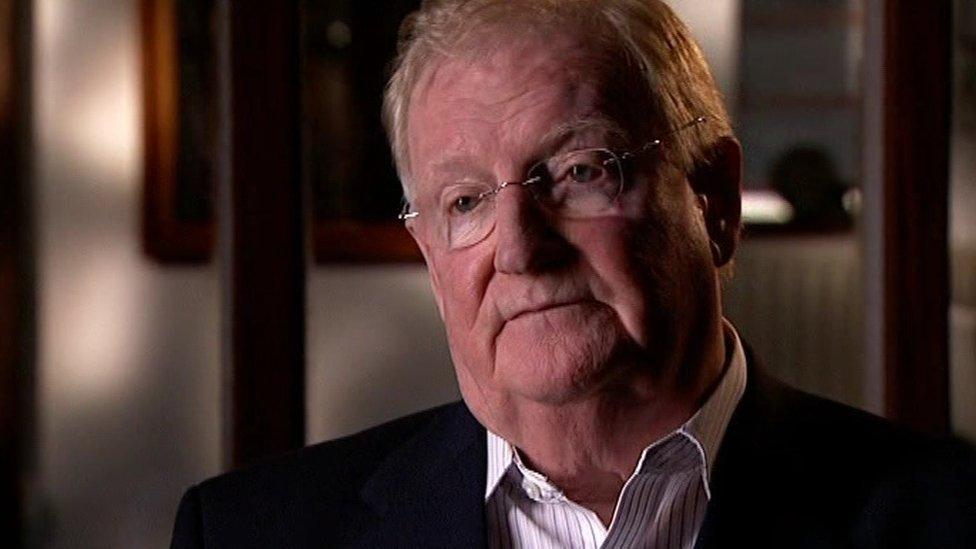

Brendan Duddy - a Londonderry businessman described as Northern Ireland's "secret peacemaker" - has died aged 80.

Publicly, his business was business; but, for almost quarter of a century, he was at the centre of an extraordinary chain of events that ultimately led to the historic IRA ceasefire of 1994 and the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

He did that by agreeing to becoming a top-secret contact between sworn enemies - the IRA and the British government.

Mr Duddy was a key link - from the early 1970s to the early 1990s - between the Provisional IRA Army Council and the Secret Intelligence Service, acting on the orders of various British governments.

He even hosted talks in his own living-room involving a top British spy and Martin McGuinness - talks that would ultimately pave the way for peace in Northern Ireland in the 1990s.

Born on 10 June 1936, Mr Duddy spent his early adult life running a family fish and chip shop in Londonderry. His wife Margo worked behind the counter. She described it as a "meeting place, where everyone came and sat and chatted".

Ironically, the beef burgers were delivered by a certain young van driver called Martin McGuinness. The same young militant republican would rise to the leadership of the IRA and one day - perhaps indirectly through Mr Duddy's peace efforts - become his country's deputy first minister. Mr McGuinness died in March.

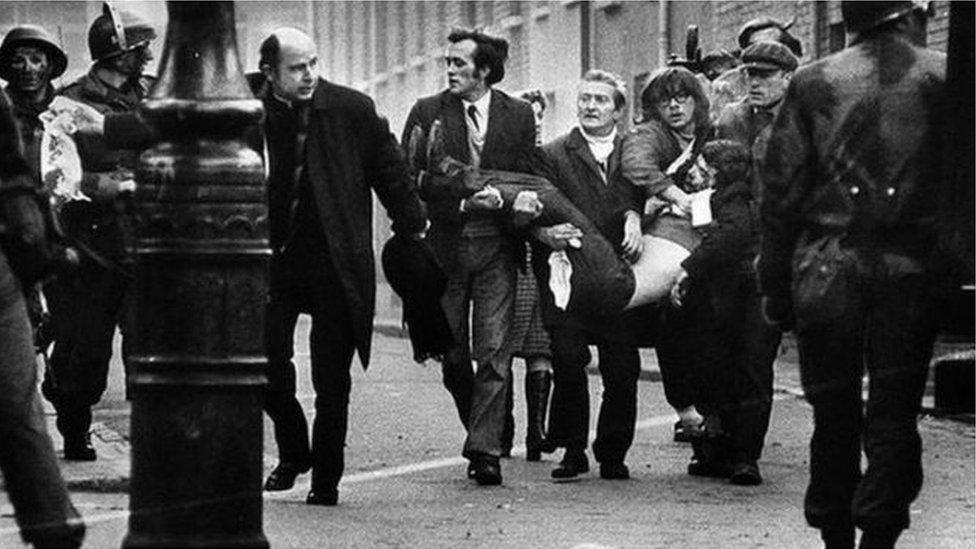

Bloody Sunday in January 1972 left 14 people dead; Mr Duddy said it would lead to 'war'

Mr Duddy's apprenticeship as intermediary came in the days before Bloody Sunday in 1972. He was asked by a friend, Frank Lagan - a fellow Catholic who happened to be Derry's police commander - to try to persuade the Provisional and Official IRA to remove their weapons from the Bogside.

After some soul-searching, Mr Duddy made contact with both organisations and they agreed to the request, with the exception of a few weapons left behind by the Officials for so-called defensive purposes.

Then came Bloody Sunday, when British paratroopers shot dead 13 civil rights marchers during an anti-internment demonstration in Derry on 30 January, 1972. A 14th died later.

'War on our hands'

Many consider the events of that day a turning point in Northern Ireland, and Mr Duddy warned Frank Lagan that it would have catastrophic consequences.

"We are going to have a war on our hands," he said.

In the ensuing violence in 1972, 479 people were killed, the highest annual death toll in what was to become known as the Troubles.

The scale of the violence only served to heighten Mr Duddy's determination to work towards peace - a goal it would take unsung heroes like him, and others, more than 20 years to achieve.

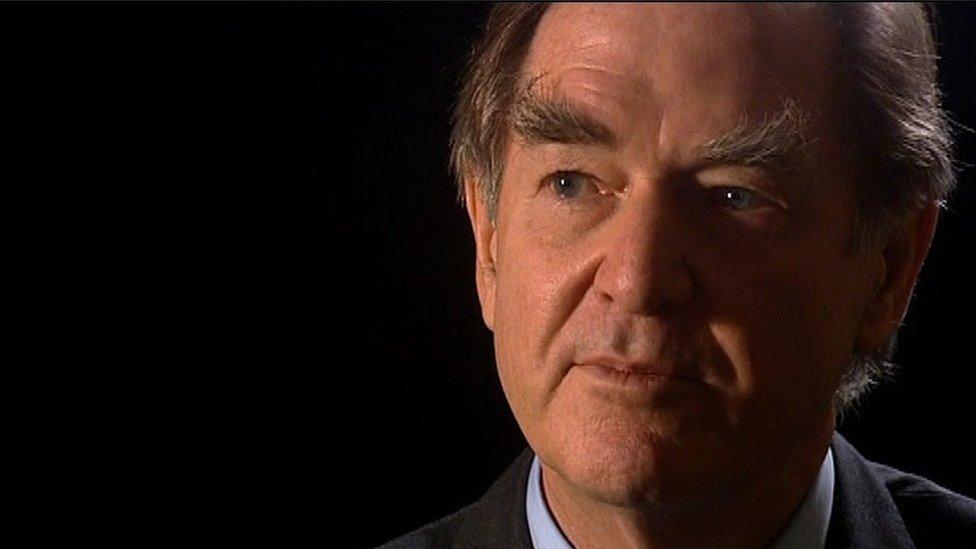

In 1973, he was introduced to a British government official he knew as Michael Oatley, who was, in fact, a spy from the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), code-named "The Mountain-Climber".

Michael Oatley, an MI6 spy, became Mr Duddy's conduit to the British government

Mr Duddy was to become the messenger between the IRA and the British government, the secret back channel who would pass messages between the two sides and, eventually, arrange meetings between them.

The process resulted in direct talks between the British and the IRA leadership in 1974-5, some of which took place in Mr Duddy's own home on Derry's Glen Road.

The republican side included IRA chief-of-staff Seamus Twomey, senior Belfast IRA commander Billy McKee, and the then Sinn Féin President Ruairí Ó Brádaigh.

During this time, the IRA declared a ceasefire, but it broke down in the face of loyalist violence and the talks ended.

Hosted talks

The process resumed during the IRA hunger strikes of 1980 and 1981, in which Bobby Sands and nine other prisoners died.

Mr Duddy, once again, was the link between the IRA and the British government under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Codenamed "Soon", Mr Duddy was a conduit for messages passed back and forth between the two sides.

Between 1997 and 2002, Brendan Duddy co-chaired talks designed to reduce tension around Derry's annual Apprentice Boys parade

During this time, "Soon" used his contacts to arrange for leading republican Danny Morrison to visit the prisoners in Long Kesh, or The Maze.

But the negotiations were fraught with difficulty, as well as a lack of trust on both sides.

It would take 10 deaths before the fast was called off in October 1981.

Days later, most of the prisoners' demands were met.

Sinn Féin was to emerge as a growing political force in Northern Ireland, as republicans now began to use the ballot box and the Armalite hand in glove.

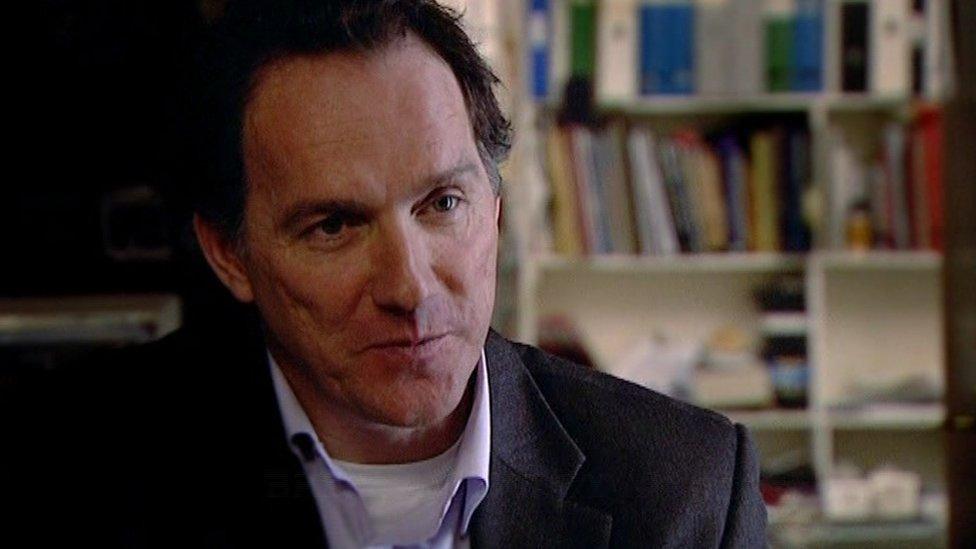

In the early 1990s, Mr Duddy hosted talks at his home between Mr Oatley and the intelligence services, and the republican leadership including the late Mr McGuinness.

Talking to the enemy had created the opportunity for peace and in 1994, after more than 3,000 deaths, the IRA declared a ceasefire.

Duddy's City of Derry Hotel Ltd bought the Ramada Hotel in Portrush in 2013

Mr Duddy's work as the secret peacemaker" was almost done - and the Good Friday peace agreement was signed four years later.

According to Martin McGuinness, Mr Duddy's successful role in the peace process was so renowned it even reached Colombia.

In 2014, Mr McGuinness said that when he met President Juan Manuel Santos, the Colombian leader told him that when his government opened a back channel with the rebel group Farc, the negotiator was codenamed "Brendan".

The peace process was not the only area in which Mr Duddy used his mediating skills.

Mr Duddy's business interests have been carried on by his family, in particular his son Brendan Duddy Jr

Between 1997 and 2002, he co-chaired talks, along with other members of Londonderry's business community, aimed at resolving tension around the city's Apprentice Boys parade. The event is now largely trouble-free.

He was also a former independent member of the Northern Ireland Policing Board.

Meanwhile, his business career thrived - the family firm, Duddy Group, has interests in property, bars, restaurants and hotels, including Derry's City Hotel and the Ramada Hotel in Portrush.

- Published12 May 2017

- Published30 August 2011