'Breakthrough' lung treatment saving premature babies

- Published

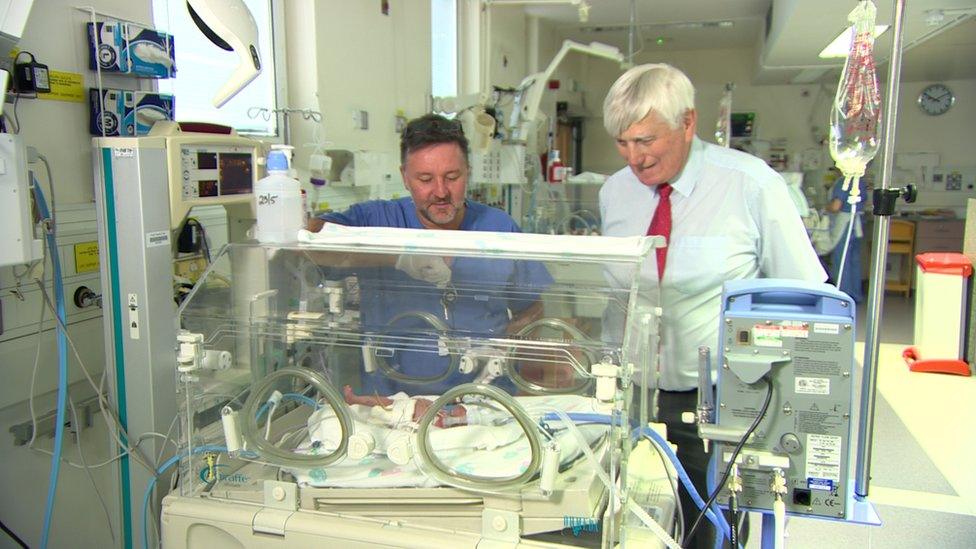

Premature babies often require a surfactant injection to help their lungs to work

Premature babies around the world are being kept alive thanks to a "medical breakthrough" that is being trialled in Belfast.

A treatment for lungs was developed in Sweden over 30 years ago and it was extracted from pigs.

However, a newer, synthetic version - that no longer relies on animal products - has now been created.

This substance, surfactant, is produced naturally in human lungs but premature babies often do not produce enough.

Dr David Sweet and Prof Henry Halliday have been at the forefront of the surfactant work in Belfast

It is made up of fats and proteins and keeps lungs moving and working.

The latest development is being trialled in Belfast's Royal Maternity Hospital.

Among those who have benefited is Lewis McIlroy, who is now two-and-a-half and lives on a farm in Magheramourne, County Antrim.

His mother, Margaret, said the medical research in Northern Ireland is fantastic.

Lewis McIlroy's life was saved by the surfactant therapy breakthrough, said his mother

"Lewis was born at 30 weeks and was very ill," she said.

"I didn't even get to hold him, he was whisked away from me by the medical team who saved his life."

Surfactant is a fluid secreted by the cells of the alveoli - the tiny air sacs in the lungs - that serves to reduce the surface tension of pulmonary fluids.

Surfactant contributes to the elastic properties of pulmonary tissue, preventing the alveoli from collapsing.

Hundreds of babies in Northern Ireland have received the treatment over the years

Premature babies often require an injection of the substance into their lungs to get them working.

Back in the 1980s it was Prof Henry Halliday who was in charge of the trial at the Royal Maternity Hospital.

Now retired and his 70s, he said that using pig lung surfactant saved many premature babies' lives and was the best available of the surfactants.

"In the 1980s when premature babies got respiratory distress syndrome due to immature lungs, if they were 28 weeks gestation or less they nearly all died," he said.

Prof Henry Halliday led the original surfactant trials in Belfast in the 1980s

"It was with the development of surfactant to replace the missing substance in the lungs that we started to see much better survival rates of these very tiny babies.

"It was a very exciting time when this drug was developed."

In 2017 times have changed and a synthetic substance has replaced that provided by pigs.

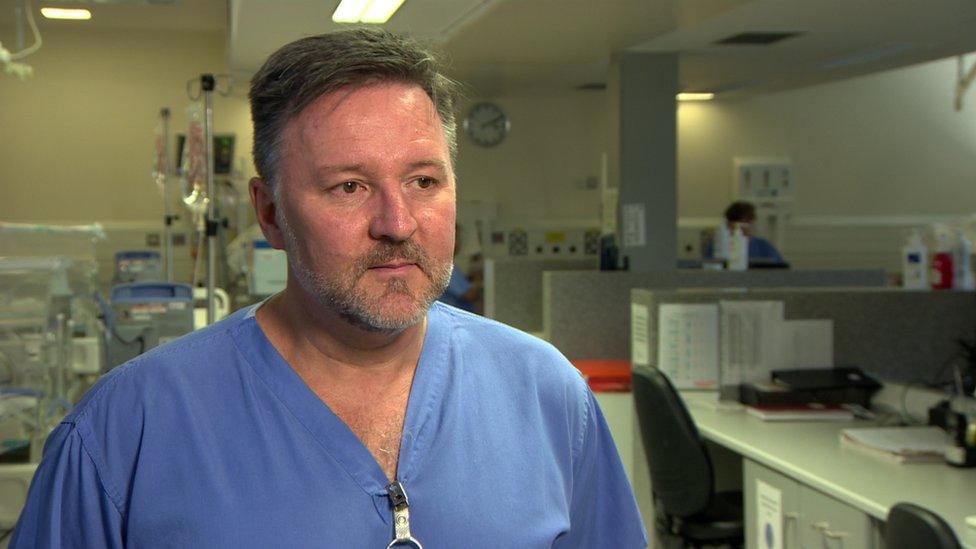

"It is a major breakthrough because we've been limited to using animal-derived surfactants for the last 30 years," said Dr David Sweet, who is leading the trials in Belfast.

The development could "herald a new era" in the therapy, said Dr David Sweet

"Now that they've been able to manufacture proteins to add to synthetic surfactant that make them work just as well, this will hopefully herald a new era of surfactant therapy."

The first child to be treated outside Sweden, where the product was invented, was in Belfast in the mid-1980s.

Since then 3.5 million babies worldwide and hundreds in Northern Ireland have received the treatment.

According to both doctors, the synthetic surfactant research extends the legacy into a new generation.

It also keeps Belfast in the centre of advanced medical trials.