NI business: Tourism and exports drive NI economy forward

- Published

Brexit dominated economic policy discussions across the island of Ireland in 2017

Brexit was 2017's major preoccupation for business - while consumers felt its continued impact through a weak pound.

Sterling was the major factor in the rise of the cost of living, as inflation peaked at a six-year high of 3.1%.

Pay was squeezed, leaving the average Northern Ireland worker earning £15-a-week less in real terms that in 2009.

But there was a plus side.

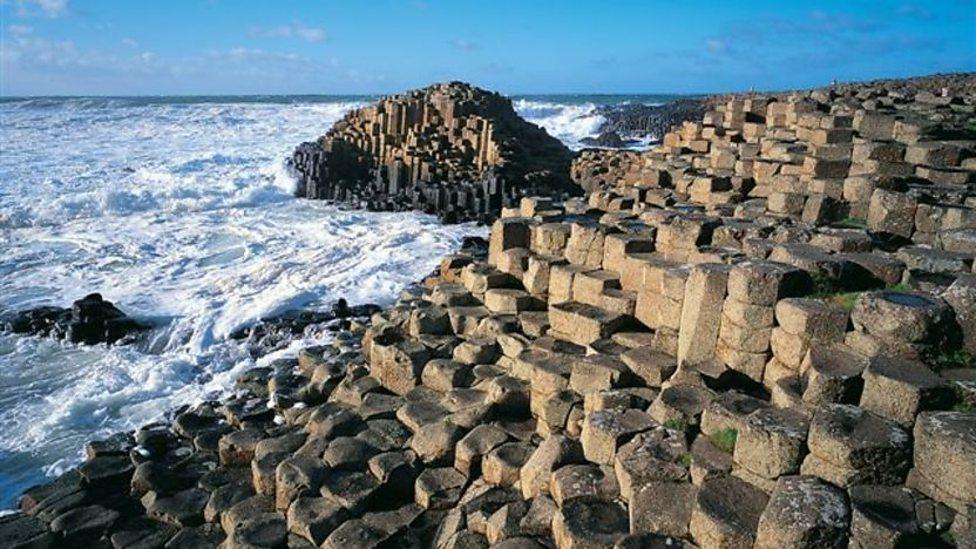

The weak pound helped drive export trade and brought tourists to Northern Ireland in record numbers.

The Giant's Causeway was NI's most popular attraction with more than 1m visitors in 2017

'Sea of uncertainty'

With Brexit negotiations due to start in earnest in 2018, businesses tried to plan as best they could.

Perhaps the most striking example was pharmaceutical firm Almac, one of Northern Ireland's star exporters, which bought two operations in the Republic of Ireland.

This is to ensure it maintains a presence in the European Union for regulatory reasons.

Northern Ireland's economy did grow over the last 12 months, albeit slowly.

Unemployment fell, but there were still blows.

Manufacturer Schlumberger posted bad news, a pending factory closure costing 220 jobs, and a trade dispute between Bombardier and Boeing threatened even more damage.

But the pressure eased somewhat on 1,000 Bombardier jobs in Belfast when Airbus acquired a controlling stake in the C-Series aircraft programme.

An agreement on phase one of the Brexit negotiations between the EU and UK was reached in early December

There was another deal with international dimensions as Craigavon-headquartered poultry firm Moy Park changed owners for £1bn.

The absence of a Northern Ireland Executive frustrated, even exasperated, some business leaders.

Stormont was meant to spend 2017 preparing for the devolution of corporation tax powers, but the big economic idea of recent times, while not shipwrecked, is drifting in a sea of uncertainty.

The average Northern Ireland worker earned £15-a-week less in real terms that in 2009

In the absence of an executive, the Westminster government had to set rates bills and then impose a budget to keep public services afloat.

An extra £1bn was promised in the DUP deal to keep the Conservatives in power, but almost all of it is still in the clutches of the Treasury.

- Published8 December 2017

- Published1 November 2017

- Published25 May 2017

- Published1 November 2017

- Published26 October 2017

- Published26 June 2017

- Published2 November 2017