Broke City - Can Londonderry's economic decline be halted?

- Published

Austins was a Derry institution established in 1830

Stand on Londonderry's Diamond and the city's economic problems seem obvious.

Austins department store, which closed two years ago, remains boarded up. Next door are two charity shops and what was a bank branch.

Look up Bishop Street and you see a closed post office, next to a closed stationery shop, next to the burnt-out remains of what was a Poundstretcher store.

This picture is reflected in the official statistics,

They show that in 2016 the employment rate in the Derry City and Strabane area was just 55%.

That means that almost half of working age adults did not have a job,

That is the lowest of any council area and compares to a Northern Ireland employment rate of 69%, with UK-wide employment sitting at 74%.

For those in work, almost one in three are employed by the public sector.

In 2017, the typical worker living in the Foyle parliamentary constituency earned £1,400 a month.

In Northern Ireland as a whole the typical worker was on £1,600 a month, and the average across the UK was almost £1,800.

On a whole range of other measurements, from deprivation to house prices to life expectancy, Derry is below the Northern Ireland average.

In some cases it has been like that for decades.

So how has this happened? And can it be fixed?

Derry's modern economic story really begins with shirt making in the late 19th century.

It was an industry built on the skills of local women and the investment of mainly Scottish entrepreneurs.

By the 1920s there were more than 40 shirt factories employing thousands of workers, with thousands more servicing the industry from their own homes.

This cluster allowed the city to grow, but the concentration on one industry also left it vulnerable.

Low wages

Graham Brownlow, an economic historian at Queen's University, said relatively low wages in shirt making also stored up trouble:

"Low wages is a very precarious basis for any location to base its economic development on."

He said that as shirt-making jobs were lost the city struggled to find new industries.

"Successful economies are those that are best able to cope with shocks, to respond to decline by growing new sectors and industries," he explained.

This story of a city, or region struggling to respond to industrial decline is not unique to Derry.

Building work at Ulster University's Magee campus

But it had other issues which perhaps made tackling this problem more difficult.

Firstly, there was the partition of Ireland. which cut Derry off from its hinterland in Donegal, though the economic impacts of this are debated.

Partition also made it difficult to co-ordinate policies for the border area.

Later in the 20th century came the Troubles. With regular bombings and poor infrastructure it made the city less than attractive for foreign direct investment.

Between partition and the Troubles, Derry, a majority nationalist city, also had to contend with a unionist government.

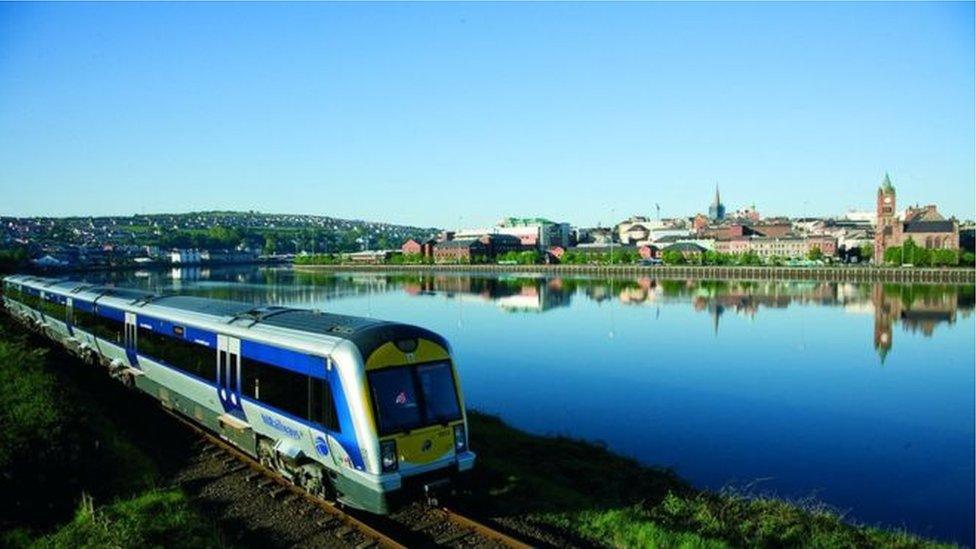

Derry held the title of the UK's first City of Culture in 2013

Steve Bradley, a regeneration expert and campaigner, said: "It's hard to conclude there wasn't some degree of discrimination against this city."

He described a city which was "deprived of the ingredients it needed to succeed."

However, Graham Brownlow is more circumspect saying official archives don't show an organised effort "to do down Derry."

But what is certain is the city lost out in 1965 when the decision was made to locate a new university in Coleraine rather than Derry.

That followed a recommendation from an independent commission led by Sir John Lockwood, an educationalist from England.

The view of many in the city was that a university would have been one of the few measures with enough impact to reverse what otherwise seemed like inevitable economic decline.

Campaign

That is an opinion still firmly held today.

Padraig Canavan's father Michael was a member of the University for Derry Committee back in 1965.

He has continued with his father's campaign:

"If you have the supply of people the companies will come, the companies will be founded here and they will be grown here," he said.

"In a modern economy you need the research and insight that a university brings.

"Without that you are continually falling behind."

Ulster University does now have a presence in Derry, but its Magee campus has only 4,000 students.

Medical school

It is committed to raising those numbers closer to 10,000 with plans for a graduate medical school well advanced.

"Nobody wants the university in this city to expand more than the university itself," said Malachy O'Neill who runs the Derry campus.

But this is not all in the gift the university. It will also need a change in government policy on student numbers.

"The funding structures for student numbers essentially limits your ability to expand your population," said Dr O'Neill

"One of the things we require is either a removal of that cap or an expansion of the existing allocation."

There are other developments happening that should help Derry's economy - an improvement of the road to Belfast is finally happening.

But without a big investment, like the university, it is hard to see how the city can make significant progress.

John Campbell examines whether radical new thinking can reverse Derry's decline in Broke City on BBC Radio Ulster at 12:30 GMT on Sunday 11 March.

- Published8 March 2016

- Published1 December 2017

- Published27 November 2014