Good Friday Agreement - 20 years on

- Published

Prime Minister Tony Blair and his Irish counterpart Bertie Ahern sign the Good Friday Agreement on 10 April 1998

If you had planned to organise a 20th birthday party for the Good Friday Agreement, you would not do it this way.

No Assembly. No power-sharing executive. No north-south ministerial meetings. Stormont unrepresented when east-west British Irish Council gatherings take place.

It feels like someone forgot to bake a cake.

Few can question the importance of the 1998 deal in human terms.

It didn't bring a complete end to violence - indeed terrible atrocities, such as the Omagh bombing, came after the people endorsed the agreement in a referendum.

But the casualty figures tell their own story.

Nearly 1,500 people died in Northern Ireland's "Troubles" during the 20 years before the deal.

By contrast there have been fewer than 150 victims of conflict-related violence over the past two decades.

The agreement was endorsed by referendums in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland

One victim is one too many, but the radically improved trend is clear.

The agreement has provided a welcome, if imperfect, peace. But it has a more chequered record when it comes to stability and good governance.

The first power-sharing executive led by the Ulster Unionists and the SDLP was plagued by difficulties.

Sharing power with enemies

These stemmed from the failure of republicans to disarm or to co-operate with the police, and the disruptive influence of a sizeable group of unionists who had always rejected the compromises made over emotive issues like early prisoner releases.

The answer, a decade ago, was to bring in those reluctant parties.

International monitors verified IRA and loyalist disarmament, Sinn Féin voted to recognise the police and the DUP agreed to what had seemed unthinkable in 1998 - sitting down to share power with their sworn republican opponents.

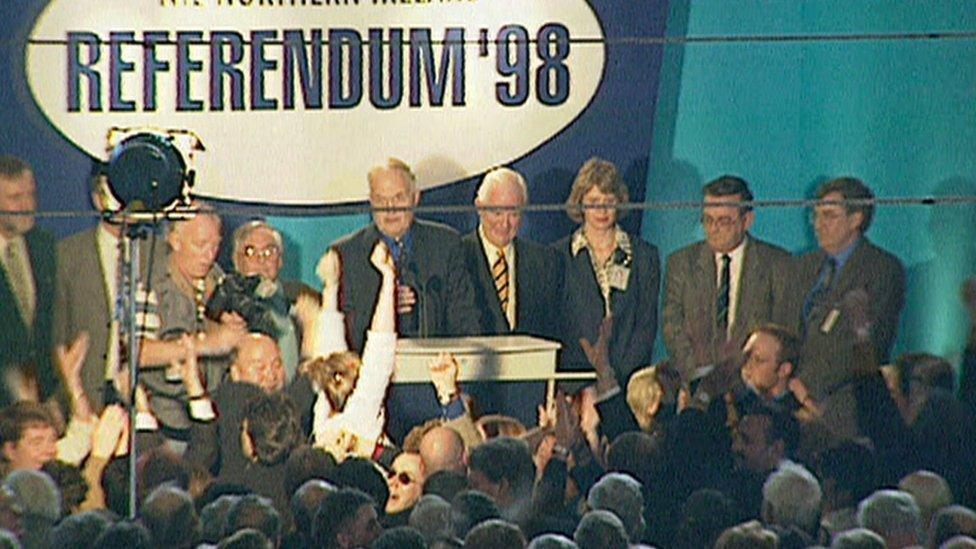

U2 singer Bono celebrates with party leaders David Trimble of the UUP and the SDLP's John Hume

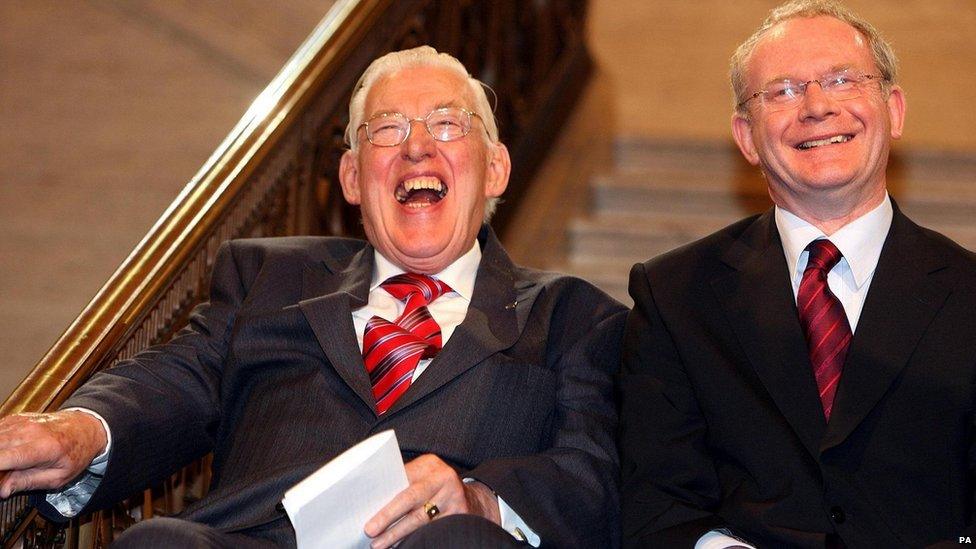

The new deal had its high points, as Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness chuckled their way into a new era.

But there were lows too, like the failure to deliver a European peace centre at the site of the old Maze jail.

Dissident republican groups tried to do their worst, loyalist paramilitaries continued to organise, while the sporadic disruption to Belfast during a dispute over limiting the days on which the Union flag could be flown at the City Hall illustrated the fragility of the new dispensation.

The latest arguments, over dealing with the legacy of the Troubles and legislating for Irish language rights, appear far more limited than the challenges overcome back in 1998. Then, both the IRA and loyalist ceasefires seemed to hang in the balance.

That said, the system of government inherited from 20 years ago has made resolving contentious issues far from straightforward.

Patrick Magee (middle), the IRA Brighton bomber, was among those released early from the Maze Prison under the auspices of the Good Friday accord

To ensure nationalist buy-in, the 1998 deal guaranteed all the major parties a foothold in the government.

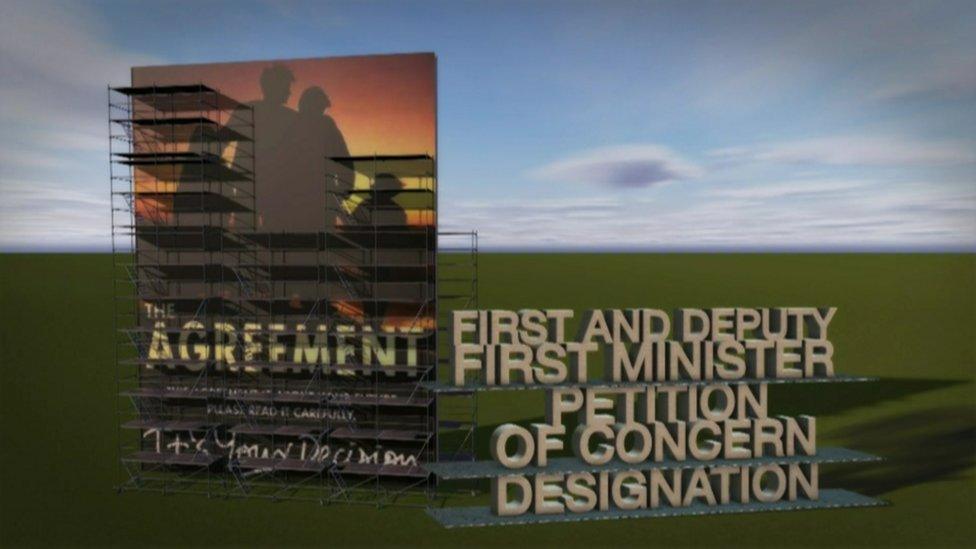

It tied the fortunes of the first and deputy first ministers inextricably together, and created a backstop called the petition of concern under which 30 assembly members can insist a controversial decision must get cross-community approval.

This network of safeguards - referred to by the former SDLP leader, Mark Durkan, as the deal's "ugly scaffolding" - provided reassurance for reluctant power sharers.

But it made for an unwieldy "lowest common denominator" form of government.

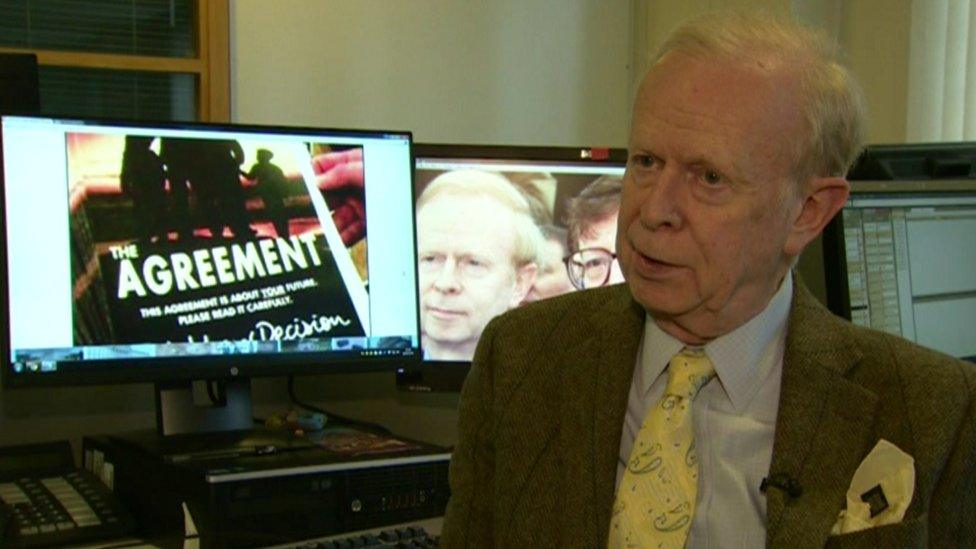

The SDLP's Mark Durkan described the agreement's network of safeguards as 'ugly scaffolding'

Tales abounded of decisions not taken and important pieces of paper languishing unsigned in the murky recesses of Stormont Castle.

Robin Wilson is strongly critical of the system bequeathed to Northern Ireland by the Good Friday Agreement negotiators.

The author of The Northern Ireland Experience of Conflict and Agreement: A Model for Export? compares the requirement for Stormont politicians to designate themselves as unionists, nationalists or others to ruling that they must wear Rangers or Celtic tops.

What has been the outcome?

Mr Wilson points out that when voters have been asked in surveys what they think the assembly has achieved they tend to say "little or nothing".

He argues that polarisation, rather than reconciliation, has been a perverse, unintended outcome of the Good Friday Agreement.

Lord Empey believes the agreement has been weakened by subsequent changes

As a senior Ulster Unionist negotiator 20 years ago, Lord Empey remains proud of what he achieved.

However, he believes that the structures created in 1998 were weakened by changes introduced to facilitate the DUP-Sinn Féin deal in 2007.

Those changes meant the first and deputy first ministers were no longer elected by MLAs as a cross-community team.

They also turned successive assembly elections into a race to the top spot with the biggest party always guaranteed the first minister's job.

On the vetoes which have been blamed for making modern-day Stormont a byword for deadlock, Lord Empey still supports the petition of concern in principle as "an insurance policy".

But he acknowledges that the mechanism "has been abused like many other things have been abused and that's unfortunate".

What can be done?

Some point to the fact that Northern Ireland's councils are still continuing to function as proof that unionists and nationalists can rub along with each other, if they must.

Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness became first and deputy first ministers following the DUP-Sinn Féin deal of 2007

Local government has its own community safeguard - the so-called "call in" procedure.

This allows a concerned group of councillors (at least 15% of the overall membership) to delay a controversial decision rather than block it altogether.

Belfast's Lord Mayor, Alliance politician Nuala McAllister, believes Stormont can learn a thing or two from the more "collegiate" spirit in many council chambers.

Ms McAllister, who was still at primary school when the 1998 deal was being negotiated, doesn't think the Good Friday Agreement has failed "but I do think that politics has failed the Good Friday Agreement".

She added: "When you look at it from the perspective of the Northern Ireland Assembly, quite frankly it's embarrassing that we may not have an assembly on the 20th anniversary of the agreement".

Lord Mayor Nuala McAllister thinks Stormont politicians could learn from local councils

In recent weeks, MPs on Westminster's Northern Ireland Affairs Committee have been taking evidence on how to move forward in the absence of an assembly and executive.

They've heard arguments about replacing the current "mandatory coalition" at Stormont, in which all the big parties get ministers, with a "voluntary coalition" where willing parties form a government and the others go into opposition.

Another idea is to ditch the cross-community majorities required for issues like same sex marriage to make progress through the assembly with a weighted majority in which, for example, the backing of 60% of MLAs might be sufficient to move forward.

Could changes to assembly protocols pave the way for same-sex marriage legislation?

Mr Wilson suggests that if a section of the 1998 deal that provided for a Northern Ireland "Bill of Rights" had been implemented, this could have been enforced through the courts.

He thinks this might have proved a better minority safeguard than the controversial petition of concern. .

But here is the conundrum - if the Stormont parties aren't able to resolve their differences over matters such as the Irish language, how likely are they to agree wholesale changes to the structures endorsed by a referendum 20 years ago?

Performers are 'blaming their instruments'

And how willing would the government be to override the wishes of any one of the key power brokers?

In her Belfast home, former Women's Coalition negotiator Monica McWilliams shows me a vibrant picture by the Belfast cartoonist Ian Knox, depicting all the 1998 negotiators as players in an orchestra.

She thinks it's not good enough for the Stormont performers to blame their instruments for the bad notes they have been hitting lately.

Pointing to the conductor she tells me: "It's political leadership that's needed and we did have it (at the time of the Good Friday Agreement) and I saw it and it worked and it needs to come back again."

Monica McWilliams says attitudes need to change

Mrs McWilliams believes the challenge is less about changing the Stormont structures and more about changing the attitudes of the politicians working the system.

"Genuinely, what people need to do is sit down and work hard to see what the other side needs" she tells me.

"It's no longer about what you want, of course we want lots of things, we know that as parents with kids, it's about what do we need?

"And it's time for us now to sell that message - that our peace agreement is still working, but this is what it needs to finish it".