Cecil Frances Alexander: A pioneer of deaf education

- Published

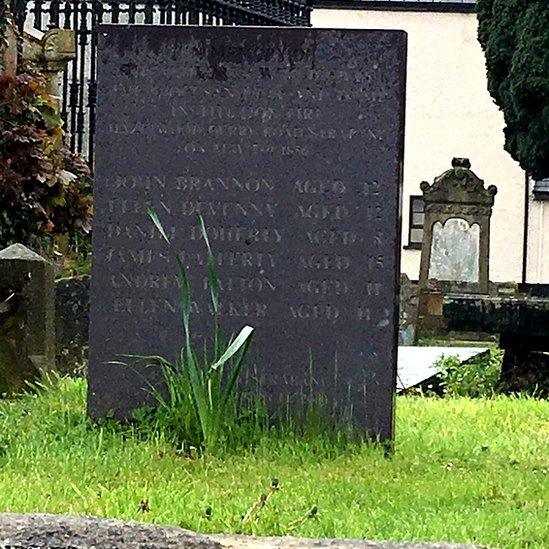

A memorial stone to the six children killed in the fire

"All things bright and beautiful, All creatures great and small…"

The classic hymn by Cecil Frances Alexander has endured the test of time, 200 years after her birth.

But few know of the part both great and small that the hymn played in transforming the education of deaf children in 19th century northern Ireland.

And fewer still know the tragedy that befell its writer's dream.

Cecil Frances (Humphreys) Alexander and her sister Anne were very involved in local church activities in Strabane, including visits to local families.

It was on one of these visits they encountered a small deaf boy from a poor home.

"They were concerned about the barrenness of his existence and the blank future he faced and also the fact he was cut off from knowledge of the love of God and the Christian way of life," said Brian Symington.

School for deaf children

Mr Symington previously led the RNID and Action on Hearing Loss in Northern Ireland and is now a British Deaf Association member.

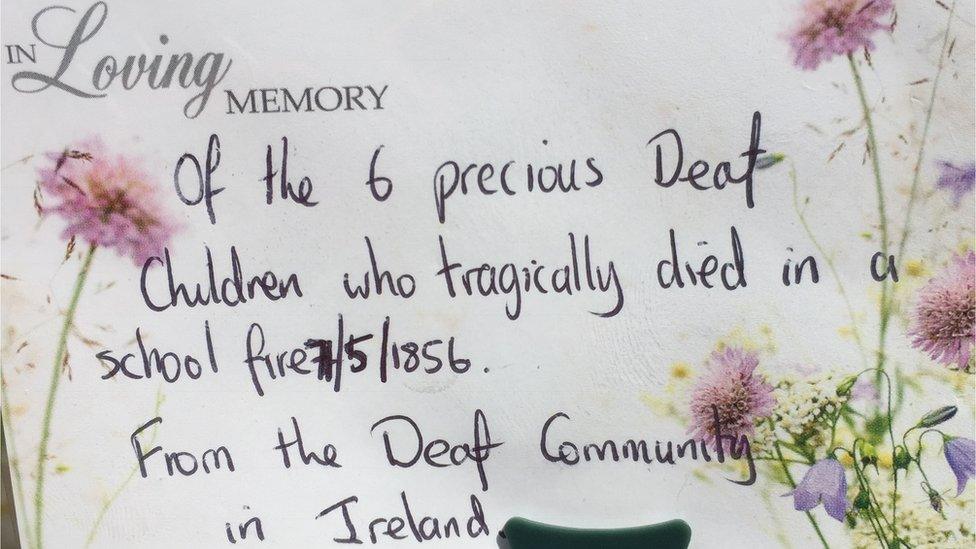

A tribute left at the scene of the tragedy

"Both sisters persuaded their father to allow them the use of a small building in the grounds of their home at Milltown House, so they could set up a tiny school for four or five deaf children," he said.

"The passion Frances had for the education of deaf children at a young age continued for the rest of her life."

From the acorn of a tiny home school, grew the dream of a large-scale institution catering to children with hearing and speech loss.

Along with other poems and hymns Frances wrote, the proceeds from her "Hymns for Little Children" collection made a significant contribution to opening what was called the Derry and Raphoe Diocesan Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb.

"'Deaf and dumb' is not a term we would use today," Mr Symington said.

"But these hymns were so descriptive and so beautiful when signed by deaf children and adults, it seems to me they were written with deaf people very much in mind."

The dream came true with the laying of the foundation stone of the school on 6th September 1850, just a few weeks before Frances got married.

Despite the Famine of the 1840s, education for deaf children had flourished, with schools opening in Belfast, Dublin and Cork. Teaching in the schools was mainly done by sign language.

The memorial is in Patrick Street Cemetery

The school Frances' literary skills helped build, first opened its doors in the summer of 1851.

Over the following five years, it welcomed almost 50 children, teaching them the skills that would help them live in a hearing world.

Meanwhile, Frances and her new husband, Church of Ireland minister William Alexander, settled happily into married life in Strabane, raising the two of their three children in the town.

Fire tragedy

On the night of 7 May 1856, the school was home to 18 boys and girls, sleeping in their separate dormitories.

The doors were locked, as they were every night, at 9pm. But some five hours later, on this night, a fire started in the kitchen and quickly took hold.

There are conflicting reports of what happened next.

Testimony from the time speaks of confusion about keys and access to the dormitories, which had high windows beyond the reach of small children.

Local people tried frantically to break glass and knock down doors to reach those who were trapped, but despite their best efforts, six children died. The oldest was 15; the youngest, just eight years old.

'Devastated'

It was eight hours later before the fire was entirely extinguished.

"Frances and William were both devastated by the fire and the deaths of the six innocent deaf children," said Mr Symington.

"Both she and her husband made great efforts following the fire to raise funding to keep a temporary school open for Deaf children in the area.

"It was hoped a new permanent school would be built but this sadly didn't materialise.

Cecil Frances Alexander was a pioneer of deaf education in Ireland

"It's said any trace of light-heartedness in Frances' writing was finally quenched in the year of the fire."

But her leading role in deaf education has not been forgotten.

Pioneer

Members of the deaf community and their friends and family visited the site of the old school in Strabane and the memorial stone that enshrines the names of the young dead to mark 162nd anniversary of the fire and 200 years since Frances' birth.

Mr Symington is determined her part will not be overlooked.

"Frances can be truly said to be a pioneer of deaf education in Ireland, particularly in the north-west," he said.

"In this, the 200th anniversary of her birth, much will be written about the impact her hymn writing has had on the world. But I hope her significant contribution to the development of education of deaf children in Ireland will not be forgotten.

"Strabane should be proud of her achievements."