Health system criticised over hyponatraemia child deaths

- Published

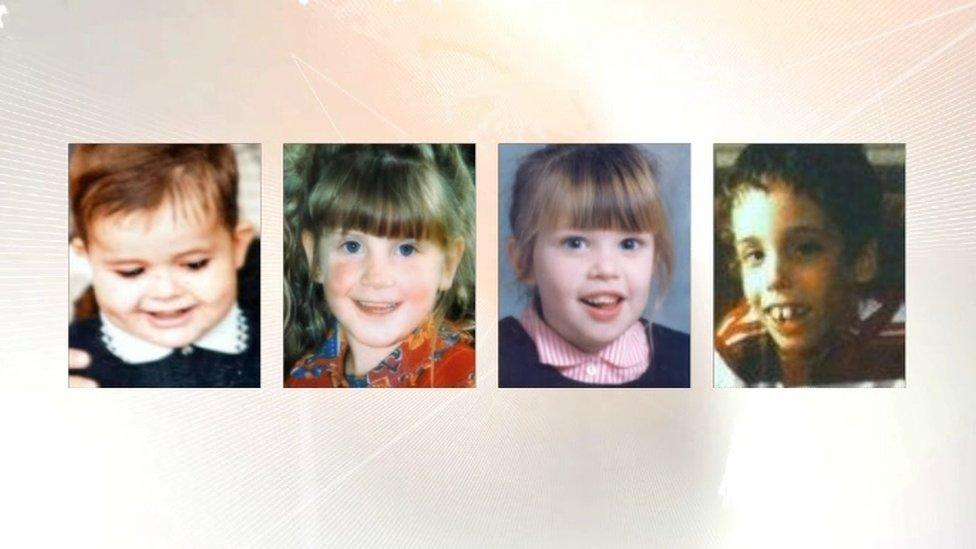

Adam Strain, Raychel Ferguson, Claire Roberts, Conor Mitchell and Lucy Crawford (not pictured) died after the level of sodium in their blood became abnormally low

NI's Department of Health could have saved the lives of some children whose deaths were investigated by the Hyponatraemia Inquiry, an expert says.

Prof Gabriel Scally said the department should have had proper systems in place.

The inquiry looked at the deaths of five children between 1995 and 2003 and found four deaths were avoidable.

The department said the serious failings in the report were a source of "shame for all involved in healthcare".

Health system criticised over hyponatraemia child deaths

It welcomed the inquiry chairman's comments that the health service environment has "most definitely been transformed".

Prof Scally, who was an adviser to the chair of the 14-year-long inquiry, said: "This is a remarkable account of lies, deceit and cover-up, of negligence and of secrecy and deliberate obstruction."

Hyponatraemia is a condition which can occur when the level of sodium in a person's blood becomes abnormally low.

Brothers meet for first time after deaths of sisters in hospitals

The inquiry looked into the deaths of Adam Strain, Claire Roberts, Raychel Ferguson, Lucy Crawford and Conor Mitchell.

Speaking exclusively to BBC News NI, Prof Scally said people clearly were not being held to account and questioned the prevailing culture among health professionals.

He also said a "toxic" relationship existed among some health professionals in Northern Ireland.

"I have seen it happen before but only in individual institutions or amongst individual teams," he said.

"Here it seems to have been a widespread pattern almost across the province."

BBC News NI Health Correspondent Marie-Louise Connolly explains the background to the hyponatraemia inquiry

He criticised how the health service was managed and the pace of response to the inquiry's 96 recommendations, external.

As well as saying the criticisms were a source of shame, the department said: "That includes the grossly deficient care provided to the children and the response of the system to the bereaved families' entirely legitimate concerns."

It also said it must do all in its power to ensure the failings were never repeated.

Who is Prof Gabriel Scally?

Specialist in public health who qualified as a doctor from Queen's University, Belfast

Born in Belfast, the 63-year-old trained in general practice and then in public health

Served for seven years as Director of Public Health in the Eastern Health and Social Services Board in NI

Held a number of senior posts in the Department of Health in England and the NHS

Holds a number of academic roles, including Professor of Public Health and Planning at the University of the West of England in Bristol

Currently carrying out a scoping exercise into the cervical cancer screening scandal in the Republic of Ireland - he is due to publish a progress report in June

Prof Scally said: "The Department of Health could have, if they had been acting properly... saved the lives of some of these children.

"The Department of Health is not the health service, it is a department of state. It is a department to serve the people and serving the people means holding the NHS to account.

"That's what they should have been doing and it doesn't look to me like they did that."

He stressed the importance of getting justice, following the publication of the hyponatraemia report.

Prof Scally said he believed that, in the absence of a local government, Northern Ireland's Chief Medical Officer, Dr Michael McBride, should break his silence over the issue and inform the public about how the system is changing.

According to Prof Scally, Dr McBride is in the unique position of having been named in the report and now, as chief medical officer, is influential in ensuring that the inquiry's recommendations are implemented.

'Clear separation'

Among the scores of doctors whose actions are heavily criticised in the report, the criticism of Dr McBride is minimal.

Dr McBride, who was medical director at the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust from August 2002 to September 2006, was involved in overseeing the trust's response to Claire Roberts' death.

In his final report, Justice O'Hara said Dr McBride's failure to insist upon his own initial suggestion of multi-professional involvement was "regrettable".

Prof Scally said: "If it was me I would say: 'I am sorry this happened and I am going to make it my professional duty for the rest of my career to make sure that this never happens again.'

"The chief medical officer, if he was involved, should talk about that and be talking to the public and talking to the families about what he has learnt from that, and to take forward the recommendations and take forward change, he might very well be the best person because he knew it from the inside.

The department said it was essential to maintain a clear separation between the department's work on the inquiry recommendations and the events examined and described by Mr Justice O'Hara in his report.

"It should also be noted that Dr McBride's leadership has helped deliver many of the important clinical and governance improvements acknowledged in Mr Justice O'Hara's report," it added.

- Published31 January 2018

- Published31 January 2018

- Published8 May 2018